A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Indo-Greek Kingdom | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 BC–AD 10 | |||||||||||||

The Elephant and the Caduceus on a coin of Demetrius I, the founder of the Indo-Greek kingdom.

| |||||||||||||

Territory of the Indo-Greeks circa 150 BC.[1] | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Alexandria in the Caucasus (modern Bagram)[2] Taxila | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Greek (Greek alphabet) Pali (Kharoshthi script) Sanskrit Prakrit (Brahmi script) | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism Hinduism Hellenism Zoroastrianism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Basileus | |||||||||||||

• 200 – 180 BC | Demetrius I (first) | ||||||||||||

• 25 BC – 10 AD | Strato III (last) | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||||||||||

• Established | 200 BC | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | AD 10 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 150 BC[3] | 1,100,000 km2 (420,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Afghanistan Pakistan India | ||||||||||||

| Indo-Greek Kingdom (200 BCE–10 CE) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Indo-Greek Kingdom |

|---|

|

The Indo-Greek Kingdom, or Graeco-Indian Kingdom, also known historically as the Yavana Kingdom (Yavanarajya),[4] was a Hellenistic-era Greek kingdom covering various parts of modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan and northwestern India.[5][6][7][8][9][10] This kingdom was in existence from c. 200 BC to c. 10 AD.

The expression "Indo-Greek Kingdom" loosely describes a number of various dynastic polities, traditionally associated with a number of regional capitals like Taxila (modern Punjab),[11] Pushkalavati, and Sagala,[12][13] but also Alexandria in the Caucasus (modern Bagram). Other potential centers are only hinted at; for instance, Ptolemy's Geographia and the nomenclature of later kings suggest that a certain Theophilus in the south of the Indo-Greek sphere of influence may also have been a satrapal or royal seat at one time.

The kingdom was founded when the Graeco-Bactrian king Demetrius (and later Eucratides) invaded India from Bactria in 200 BC.[14] The Greeks in the Indian Subcontinent were eventually divided from the Graeco-Bactrians centered on Bactria (now the border between Afghanistan and Uzbekistan), and the Indo-Greeks in the present-day North Western Indian Subcontinent.[15]

During the two centuries of their rule, the Indo-Greek kings combined the Greek and Indian languages and symbols, as seen on their coins, and blended Greek and Indian ideas, as seen in the archaeological remains.[16] The diffusion of Indo-Greek culture had consequences which are still felt today, particularly through the influence of Greco-Buddhist art.[17] The ethnicity of the Indo-Greek may also have been hybrid to some degree. Euthydemus I was, according to Polybius,[18] a Magnesian Greek. His son, Demetrius I, founder of the Indo-Greek kingdom, was therefore of Greek ethnicity at least by his father. A marriage treaty was arranged for the same Demetrius with a daughter of the Seleucid ruler Antiochus III. The ethnicity of later Indo-Greek rulers is sometimes less clear.[19] For example, Artemidoros (80 BC) was supposed to have been of Indo-Scythian descent, although he is now seen as a regular Indo-Greek king.[20]

Menander I, being the most well known amongst the Indo-Greek kings, is often referred to simply as "Menander," despite the fact that there was indeed another Indo-Greek King known as Menander II. Menander I's capital was at Sagala in the Punjab (present-day Sialkot). Following the death of Menander, most of his empire splintered and Indo-Greek influence was considerably reduced. Many new kingdoms and republics east of the Ravi River began to mint new coinage depicting military victories.[21] The most prominent entities to form were the Yaudheya Republic, Arjunayanas, and the Audumbaras. The Yaudheyas and Arjunayanas both are said to have won "victory by the sword".[22] The Datta dynasty and Mitra dynasty soon followed in Mathura.

The Indo-Greeks ultimately disappeared as a political entity around 10 AD following the invasions of the Indo-Scythians, although pockets of Greek populations probably remained for several centuries longer under the subsequent rule of the Indo-Parthians, the Kushans,[a] and the Indo-Scythians, whose Western Satraps state lingered on encompassing local Greeks, up to 415 CE.

Background

Initial Greek presence in the Indian subcontinent

Greeks first began to settle the Northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent during the time of the Persian Achaemenid empire. Darius the Great conquered the area, but along with his successors also conquered much of the Greek world, which at the time included all of the western Anatolian peninsula. When Greek villages rebelled under the Persian yoke, they were sometimes ethnically cleansed, by relocation to the far side of the empire. Thus there came to be many Greek communities in the Indian parts of the Persian empire.[citation needed]

In the fourth century BC, Alexander the Great defeated and conquered the Persian empire. In 326 BC, this included the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent as far as the Hyphasis River. Alexander established satrapies and founded several settlements, including Bucephala; he turned south when his troops refused to go further east.[23] The Indian satrapies of the Punjab were left to the rule of Porus and Taxiles, who were confirmed again at the Treaty of Triparadisus in 321 BC, and the remaining Greek troops in these satrapies were left under the command of Alexander's general Eudemus. After 321 BC Eudemus toppled Taxiles, until he left India in 316 BC. To the south, another general also ruled over the Greek colonies of the Indus: Peithon, son of Agenor,[24] until his departure for Babylon in 316 BC.

Around 322 BC, the Greeks (described as Yona or Yavana in Indian sources) may then have participated, together with other groups, in the uprising of Chandragupta Maurya against the Nanda dynasty, and gone as far as Pataliputra for the capture of the city from the Nandas. The Mudrarakshasa of Visakhadutta as well as the Jaina work Parisishtaparvan talk of Chandragupta's alliance with the Himalayan king Parvatka, often identified with Porus,[25] and according to these accounts, this alliance gave Chandragupta a composite and powerful army made up of Yavanas (Greeks), Kambojas, Shakas (Scythians), Kiratas (Nepalese), Parasikas (Persians) and Bahlikas (Bactrians) who took Pataliputra.[26][27][28]

In 305 BC, Seleucus I led an army to the Indus, where he encountered Chandragupta. The confrontation ended with a peace treaty, and "an intermarriage agreement" (Epigamia, Greek: Ἐπιγαμία), meaning either a dynastic marriage or an agreement for intermarriage between Indians and Greeks. Accordingly, Seleucus ceded his eastern territories to Chandragupta, possibly as far as Arachosia and received 500 war elephants (which played a key role in Seleucus's victory at the Battle of Ipsus):[29]

The Indians occupy in part some of the countries situated along the Indus, which formerly belonged to the Persians: Alexander deprived the Ariani of them, and established there settlements of his own. But Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus in consequence of a marriage contract, and received in return five hundred elephants.

The details of the marriage agreement are not known,[31] but since the extensive sources available on Seleucus never mention an Indian princess, it is thought that the marital alliance went the other way, with Chandragupta himself or his son Bindusara marrying a Seleucid princess, in accordance with contemporary Greek practices to form dynastic alliances. An Indian Puranic source, the Pratisarga Parva of the Bhavishya Purana, described the marriage of Chandragupta with a Greek ("Yavana") princess, daughter of Seleucus,[32] before accurately detailing early Mauryan genealogy:

"Chandragupta married with a daughter of Suluva, the Yavana king of Pausasa. Thus, he mixed the Buddhists and the Yavanas. He ruled for 60 years. From him, Vindusara was born and ruled for the same number of years as his father. His son was Ashoka."

Chandragupta, however, followed Jainism until the end of his life. He got in his court for marriage the daughter of Seleucus Nicator, Berenice (Suvarnnaksi), and thus, he mixed the Indians and the Greeks. His grandson Ashoka, as Woodcock and other scholars have suggested, "may in fact have been half or at least a quarter Greek."[35]

Also several Greeks, such as the historian Megasthenes,[36] followed by Deimachus and Dionysius, were sent to reside at the Mauryan court.[37] Presents continued to be exchanged between the two rulers.[38] The intensity of these contacts is testified by the existence of a dedicated Mauryan state department for Greek (Yavana) and Persian foreigners,[39] or the remains of Hellenistic pottery that can be found throughout northern India.[40]

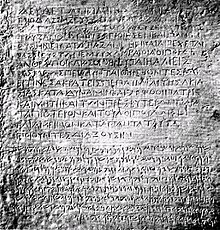

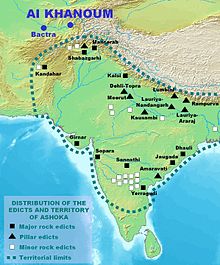

On these occasions, Greek populations apparently remained in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent under Mauryan rule. Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka, who had converted to the Buddhist faith declared in the Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, some of them written in Greek,[41][42] that Greek populations within his realm also had converted to Buddhism:[43]

Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dharma.

— Rock Edict Nb13 (S. Dhammika).

In his edicts, Ashoka mentions that he had sent Buddhist emissaries to Greek rulers as far as the Mediterranean (Edict No. 13),[44][45] and that he developed herbal medicine in their territories, for the welfare of humans and animals (Edict No. 2).[46]

The Greeks in India even seem to have played an active role in the propagation of Buddhism, as some of the emissaries of Ashoka such as Dharmaraksita,[47] or the teacher Mahadharmaraksita,[48] are described in Pali sources as leading Greek ("Yona", i.e., Ionian) Buddhist monks, active in Buddhist proselytism (the Mahavamsa, XII).[49] It is also thought that Greeks contributed to the sculptural work of the Pillars of Ashoka,[50] and more generally to the blossoming of Mauryan art.[51] Some Greeks (Yavanas) may have played an administrative role in the territories ruled by Ashoka: the Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman records that during the rule of Ashoka, a Yavana King/ Governor named Tushaspha was in charge in the area of Girnar, Gujarat, mentioning his role in the construction of a water reservoir.[52][53]

Again in 206 BC, the Seleucid emperor Antiochus led an army to the Kabul valley, where he received war elephants and presents from the local king Sophagasenus:[54]

He (Antiochus) crossed the Caucasus (the Caucasus Indicus or Paropamisus: mod. Hindú Kúsh) and descended into India; renewed his friendship with Sophagasenus the king of the Indians; received more elephants, until he had a hundred and fifty altogether; and having once more provisioned his troops, set out again personally with his army: leaving Androsthenes of Cyzicus the duty of taking home the treasure which this king had agreed to hand over to him.

Greek rule in Bactria

Alexander had also established several colonies in neighbouring Bactria, such as Alexandria on the Oxus (modern Ai-Khanoum) and Alexandria of the Caucasus (medieval Kapisa, modern Bagram). After Alexander's death in 323 BC, Bactria came under the control of Seleucus I Nicator, who founded the Seleucid Empire. The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom was founded when Diodotus I, the satrap of Bactria (and probably the surrounding provinces) seceded from the Seleucid Empire around 250 BC. The preserved ancient sources (see below) are somewhat contradictory and the exact date of Bactrian independence has not been settled. Somewhat simplified, there is a high chronology (c. 255 BC) and a low chronology (c. 246 BC) for Diodotos' secession.[57] The high chronology has the advantage of explaining why the Seleucid king Antiochus II issued very few coins in Bactria, as Diodotos would have become independent there early in Antiochus' reign.[58] On the other hand, the low chronology, from the mid-240s BC, has the advantage of connecting the secession of Diodotus I with the Third Syrian War, a catastrophic conflict for the Seleucid Empire.

Diodotus, the governor of the thousand cities of Bactria (Latin: Theodotus, mille urbium Bactrianarum praefectus), defected and proclaimed himself king; all the other people of the Orient followed his example and seceded from the Macedonians.

The new kingdom, highly urbanized and considered one of the richest of the Orient (opulentissimum illud mille urbium Bactrianum imperium "The extremely prosperous Bactrian empire of the thousand cities" Justin, XLI,1[60]), was to further grow in power and engage into territorial expansion to the east and the west:

The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Ariana, but also of India, as Apollodorus of Artemita says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander... Their cities were Bactra (also called Zariaspa, through which flows a river bearing the same name and emptying into the Oxus), and Darapsa, and several others. Among these was Eucratidia, which was named after its ruler.

— (Strabo, XI.XI.I[61])

When the ruler of neighbouring Parthia, the former satrap and self-proclaimed king Andragoras, was eliminated by Arsaces, the rise of the Parthian Empire cut off the Greco-Bactrians from direct contact with the Greek world. Overland trade continued at a reduced rate, while sea trade between Greek Egypt and Bactria developed.

Diodotus was succeeded by his son Diodotus II, who allied himself with the Parthian Arsaces in his fight against Seleucus II:

Soon after, relieved by the death of Diodotus, Arsaces made peace and concluded an alliance with his son, also by the name of Diodotus; some time later he fought against Seleucos who came to punish the rebels, and he prevailed: the Parthians celebrated this day as the one that marked the beginning of their freedom

— (Justin, XLI,4)[62]

Euthydemus, a Magnesian Greek according to Polybius[63] and possibly satrap of Sogdiana, overthrew Diodotus II around 230 BC and started his own dynasty. Euthydemus's control extended to Sogdiana, going beyond the city of Alexandria Eschate founded by Alexander the Great in Ferghana:

"And they also held Sogdiana, situated above Bactriana towards the east between the Oxus River, which forms the boundary between the Bactrians and the Sogdians, and the Iaxartes River. And the Iaxartes forms also the boundary between the Sogdians and the nomads.

— Strabo XI.11.2[64]

Euthydemus was attacked by the Seleucid ruler Antiochus III around 210 BC. Although he commanded 10,000 horsemen, Euthydemus initially lost a battle on the Arius[65] and had to retreat. He then successfully resisted a three-year siege in the fortified city of Bactra (modern Balkh), before Antiochus finally decided to recognize the new ruler, and to offer one of his daughters to Euthydemus's son Demetrius around 206 BC.[66] Classical accounts also relate that Euthydemus negotiated peace with Antiochus III by suggesting that he deserved credit for overthrowing the original rebel Diodotus, and that he was protecting Central Asia from nomadic invasions thanks to his defensive efforts:

...for if he did not yield to this demand, neither of them would be safe: seeing that great hordes of Nomads were close at hand, who were a danger to both; and that if they admitted them into the country, it would certainly be utterly barbarised.

Following the departure of the Seleucid army, the Bactrian kingdom seems to have expanded. In the west, areas in north-eastern Iran may have been absorbed, possibly as far as into Parthia, whose ruler had been defeated by Antiochus the Great. These territories possibly are identical with the Bactrian satrapies of Tapuria and Traxiane.

To the north, Euthydemus also ruled Sogdiana and Ferghana, and there are indications that from Alexandria Eschate the Greco-Bactrians may have led expeditions as far as Kashgar and Ürümqi in Chinese Turkestan, leading to the first known contacts between China and the West around 220 BC. The Greek historian Strabo too writes that:

they extended their empire even as far as the Seres (Chinese) and the Phryni

Several statuettes and representations of Greek soldiers have been found north of the Tien Shan, on the doorstep to China, and are today on display in the Xinjiang museum at Urumqi (Boardman[67]).

Greek influences on Chinese art have also been suggested (Hirth, Rostovtzeff). Designs with rosette flowers, geometric lines, and glass inlays, suggestive of Hellenistic influences,[68] can be found on some early Han dynasty bronze mirrors.[69]

Numismatics also suggest that some technology exchanges may have occurred on these occasions: the Greco-Bactrians were the first in the world to issue cupro-nickel (75/25 ratio) coins,[70] an alloy technology only known by the Chinese at the time under the name "White copper" (some weapons from the Warring States period were in copper-nickel alloy[71]). The practice of exporting Chinese metals, in particular iron, for trade is attested around that period. Kings Euthydemus, Euthydemus II, Agathocles and Pantaleon made these coin issues around 170 BC and it has alternatively been suggested that a nickeliferous copper ore was the source from mines at Anarak.[72] Copper-nickel would not be used again in coinage until the 19th century.

The presence of Chinese people in the Indian subcontinent from ancient times is also suggested by the accounts of the "Ciñas" in the Mahabharata and the Manu Smriti.

The Han dynasty explorer and ambassador Zhang Qian visited Bactria in 126 BC, and reported the presence of Chinese products in the Bactrian markets:

"When I was in Bactria (Daxia)", Zhang Qian reported, "I saw bamboo canes from Qiong and cloth made in the province of Shu (territories of southwestern China). When I asked the people how they had gotten such articles, they replied, "Our merchants go buy them in the markets of Shendu (India)."

Upon his return, Zhang Qian informed the Chinese emperor Han Wudi of the level of sophistication of the urban civilizations of Ferghana, Bactria and Parthia, who became interested in developing commercial relationships with them:

The Son of Heaven on hearing all this reasoned thus: Ferghana (Dayuan) and the possessions of Bactria (Daxia) and Parthia (Anxi) are large countries, full of rare things, with a population living in fixed abodes and given to occupations somewhat identical with those of the Chinese people, and placing great value on the rich produce of China

— (Hanshu, Former Han History)

A number of Chinese envoys were then sent to Central Asia, triggering the development of the Silk Road from the end of the 2nd century BC.[73]

The Indian emperor Chandragupta, founder of the Mauryan dynasty, had re-conquered northwestern India upon the death of Alexander the Great around 322 BC. However, contacts were kept with his Greek neighbours in the Seleucid Empire, a dynastic alliance or the recognition of intermarriage between Greeks and Indians were established (described as an agreement on Epigamia in Ancient sources), and several Greeks, such as the historian Megasthenes, resided at the Mauryan court. Subsequently, each Mauryan emperor had a Greek ambassador at his court.

Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka converted to the Buddhist faith and became a great proselytizer in the line of the traditional Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism, directing his efforts towards the Indian and the Hellenistic worlds from around 250 BC. According to the Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, some of them written in Greek, he sent Buddhist emissaries to the Greek lands in Asia and as far as the Mediterranean. The edicts name each of the rulers of the Hellenistic world at the time.

The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (4,000 miles) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni.

— (Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika)

Some of the Greek populations that had remained in northwestern India apparently converted to Buddhism:

Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dharma.

— (Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika)

Furthermore, according to Pali sources, some of Ashoka's emissaries were Greek Buddhist monks, indicating close religious exchanges between the two cultures:

When the thera (elder) Moggaliputta, the illuminator of the religion of the Conqueror (Ashoka), had brought the (third) council to an end… he sent forth theras, one here and one there: …and to Aparantaka (the "Western countries" corresponding to Gujarat and Sindh) he sent the Greek (Yona) named Dhammarakkhita... and the thera Maharakkhita he sent into the country of the Yona.

— (Mahavamsa XII)

Greco-Bactrians probably received these Buddhist emissaries (At least Maharakkhita, lit. "The Great Saved One", who was "sent to the country of the Yona") and somehow tolerated the Buddhist faith, although little proof remains. In the 2nd century AD, the Christian dogmatist Clement of Alexandria recognized the existence of Buddhist Sramanas among the Bactrians ("Bactrians" meaning "Oriental Greeks" in that period), and even their influence on Greek thought:

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Indo-Greeks

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk