A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Year | Number |

|---|---|

| 1980[5] | 40,165,702

|

| 1990[6] | 38,735,539

|

| 2000[7] | 30,528,492

|

| 2010[8] | 34,670,009

|

| 2020[9] | 38,597,428

|

| Part of a series on |

| Irish people |

|---|

|

| By region or country |

| Irish culture |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

| History of Ireland |

Irish Americans are ethnic Irish who live in the United States and are American citizens. Most Irish Americans of the 21st century are descendants of immigrants who moved to the United States in the mid-19th century because of The Great Famine in Ireland.[10]

Irish immigration to the United States

From the 17th century to the mid-19th century

This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (May 2023) |

Some of the first Irish people to travel to the New World did so as members of the Spanish garrison in Florida during the 1560s. Small numbers of Irish colonists were involved in efforts to establish colonies in the Amazon region, in Newfoundland, and in Virginia between 1604 and the 1630s. According to historian Donald Akenson, there were "few if any" Irish forcibly transported to the Americas during this period.[15]

Irish immigration to the Americas was the result of a series of complex causes. The Tudor conquest and subsequent colonization by English and Scots people during the 16th and 17th centuries had led to widespread social upheaval in Ireland. Many Irish people tried to seek a better life elsewhere.

At the time European colonies were being founded in the Americas, offering destinations for emigration. Most Irish immigrants to the Americas traveled as indentured servants, with their passage paid for a wealthier person to whom they owed labor for a period of time. Some were merchants and landowners, who served as key players in a variety of different mercantile and colonizing enterprises.[15]

In the 1620s significant numbers of Irish laborers began traveling to English colonies such as Virginia on the continent, and the Leeward Islands and Barbados in the Caribbean region.[16]: 56–7

Half of the Irish immigrants to the United States in its colonial era (1607–1775) came from the Irish province of Ulster and were largely Protestant, while the other half came from the other three provinces (Leinster, Munster, and Connacht).[17]

In the 17th century, immigration from Ireland to the Thirteen Colonies was minimal,[18][19] confined mostly to male Irish indentured servants who were primarily Catholic[19][20] and peaked with 8,000 prisoner-of-war penal transports to the Chesapeake Colonies from the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in the 1650s (out of a total of approximately 10,000 Catholic immigrants from Ireland to the United States prior to the American Revolutionary War in 1775).[19][21][22][23]

Indentured servitude in British America emerged in part due to the high cost of passage across the Atlantic Ocean.[24][25] Indentured servants followed their patrons to the latter's choice of colonies as destinations.[26]

While the Colony of Virginia established the Anglican Church as the official religion, and passed laws prohibiting the free exercise of Catholicism during the colonial period,[27] the General Assembly of the Province of Maryland enacted laws in 1639 protecting freedom of religion (following the instructions of a 1632 letter from Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore to his brother Leonard Calvert, the 1st Proprietary-Governor of Maryland). The Maryland General Assembly later passed the 1649 Maryland Toleration Act explicitly guaranteeing those privileges for Catholics.[28]

Like the rest of the indentured servant population (who were mostly men) in the Chesapeake Colonies at the time, 40 to 50 percent died before completing their contracts. Conditions were harsh and the Tidewater region had a highly malignant disease environment, with mosquitoes spreading disease. Most of the men did not establish families and died childless because the population of the Chesapeake Colonies, like the Thirteen Colonies in the aggregate, was not sex-balanced until the 18th century. Three-quarters of the immigrants to the Chesapeake Colonies were male (and in some periods, 4:1 or 6:1 male-to-female) and fewer than 1 percent were over the age of 35. As a consequence, the population grew only because of sustained immigration rather than natural increase. Many of those who survived their indentured servitude contracts left the region.[29][30][31]

In 1650, all five Catholic churches with regular services in the eight British American colonies were located in Maryland.[32]

The Province of Carolina did not restrict suffrage to members of the established Anglican church. In contrast to 17th century Maryland, the New England colonies had a variety of policies. Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut Colonies restricted suffrage to members of the established Puritan church. The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations had no established church, while the former New Netherland colonies (New York, New Jersey, and Delaware) had no established church under the Duke's Laws. The Frame of Government in William Penn's 1682 land grant established free exercise of religion for all Christians in the Province of Pennsylvania.[33][34]

Following the Glorious Revolution (1688–1689), colonial governments disenfranchised Catholics in Maryland, New York, Rhode Island, Carolina, and Virginia.[33] In Maryland, suffrage was restored in 1702.[35]

In 1692, the Maryland General Assembly had established the Church of England as the official state church.[36] In 1698 and 1699, Maryland, Virginia, and Carolina passed laws specifically limiting immigration of Irish Catholic indentured servants.[37] In 1700, the estimated population of Maryland was 29,600,[38] about 2,500 of whom were Catholic.[39]

In the 18th century, emigration from Ireland to the Thirteen Colonies shifted from being primarily Catholic to being primarily Protestant. With the exception of the 1790s, it would remain so until the mid-to-late 1830s,[40][41] with Presbyterians constituting the absolute majority until 1835.[42][43] These Protestant immigrants were principally descended from Scottish and English pastoralists and colonial administrators (often from the South/Lowlands of Scotland and the bordering North of England) who had in the previous century settled the Plantations of Ireland, the largest of which was the Plantation of Ulster.[44][45][46] By the late 18th century, these Protestant immigrants primarily migrated as families rather than as individuals.[47] Most of these Irish Protestants were Ulster Protestants. During the first half of the 18th century, 15,000 Ulster Protestants emigrated to North America, with another 25,000 during the period 1751 to 1775. The reasons for their emigration consisted mainly of: bad harvests, landlords increasing rents as leases fell through, and agrarian violence by Protestant gangs such as the "Hearts of Steel", also known as the "Steelboys", before the American revolution cut off further emigration.[48]

In 1704, the Maryland General Assembly passed a law that banned the Jesuits from proselytizing, baptizing children other than those with Catholic parents, and publicly conducting Catholic Mass. Two months after its passage, the General Assembly modified the legislation to allow Mass to be privately conducted for an 18-month period. In 1707, the General Assembly passed a law which permanently allowed Mass to be privately conducted. During this period, the General Assembly also began levying taxes on the passage of Irish Catholic indentured servants. In 1718, the General Assembly required a religious test for voting that resumed disenfranchisement of Catholics.[49]

However, lax enforcement of penal laws in Maryland (due to its population being overwhelmingly rural) enabled churches on Jesuit-operated farms and plantations to serve growing populations and become stable parishes.[50]

In 1750, of the 30 Catholic churches with regular services in the Thirteen Colonies, 15 were located in Maryland, 11 in Pennsylvania, and 4 in the former New Netherland colonies.[51] By 1756, the number of Catholics in Maryland had increased to approximately 7,000,[52] which increased further to 20,000 by 1765.[50] In Pennsylvania, there were approximately 3,000 Catholics in 1756 and 6,000 by 1765 (the large majority of the Pennsylvania Catholic population was from provinces of southern Germany).[50][52][53]

From 1717 to 1775, though scholarly estimates vary, the most common approximation is that 250,000 immigrants from Ireland emigrated to the Thirteen Colonies.[list 1] By the beginning of the American Revolutionary War in 1775, approximately only 2 to 3 percent of the colonial labor force was composed of indentured servants, and of those arriving from Britain from 1773 to 1776, fewer than 5 percent were from Ireland (while 85 percent remained male and 72 percent went to the Southern Colonies).[63] Immigration during the war came to a standstill except by 5,000 German mercenaries from Hesse who remained in the country following the war.[41] Out of the 115 killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill, 22 were Irish-born. Their names include Callaghan, Casey, Collins, Connelly, Dillon, Donohue, Flynn, McGrath, Nugent, Shannon, and Sullivan.[64]

By the end of the war in 1783, there were approximately 24,000 to 25,000 Catholics in the United States (including 3,000 slaves) out of a total population of approximately 3 million (or less than 1 percent).[38][21][65][66] The majority of the Catholic population in the United States during the colonial period came from England, Germany, and France, not Ireland.[21] Irish historiographers tried and failed to demonstrate Irish Catholics were more numerous in the colonial period than previous scholarship had indicated.[67] By 1790, approximately 400,000 people of Irish birth or ancestry lived in the United States (or greater than 10 percent of the total population of approximately 3.9 million).[17][68] The U.S. Bureau of the Census estimates 2% of the United States population in 1776 was of native Irish heritage.[69] The Catholic population grew to approximately 50,000 by 1800 (or less than 1 percent of the total population of approximately 5.3 million) due to increased Catholic emigration from Ireland during the 1790s.[41][66][70][71]

In the 18th century Thirteen Colonies and the independent United States, while interethnic marriage among Catholics remained a dominant pattern, Catholic-Protestant intermarriage became more common (notably in the Shenandoah Valley where intermarriage among Ulster Protestants and the significant minority of Irish Catholics in particular was not uncommon or stigmatized).[72] While fewer Catholic parents required that their children be disinherited in their wills if they renounced Catholicism, compared to the rest of the US population, this response was more common among Catholic parents that Protestants.[65]

Despite such contstraints, many Irish Catholics who immigrated to the United States from 1770 to 1830 converted to Baptist and Methodist churches during the Second Great Awakening (1790–1840).[73][74]

Between the end of the American Revolutionary War in 1783 and the War of 1812, 100,000 immigrants came from Ulster to the United States.[42] During the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802) and Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), there was a 22-year economic expansion in Ireland due to increased need for agricultural products for British soldiers and an expanding population in England. Following the conclusion of the War of the Seventh Coalition and Napoleon's exile to Saint Helena in 1815, there was a six-year international economic depression that led to plummeting grain prices and a cropland rent spike in Ireland.[42][75]

From 1815 to 1845, 500,000 more Irish Protestant immigrants came from Ireland to the United States,[42][76] as part of a migration of approximately 1 million immigrants from Ireland from 1820 to 1845.[75] In 1820, following the Louisiana Purchase in 1804 and the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1819, and acquisition of territories formerly controlled by Catholic European nations, the Catholic population of the United States had grown to 195,000 (or approximately 2 percent of the total population of approximately 9.6 million).[77][78] By 1840, along with resumed immigration from Germany by the 1820s,[79] the Catholic population grew to 663,000 (or approximately 4 percent out of the total population of 17.1 million).[80][81] Following the potato blight in late 1845 that initiated the Great Famine in Ireland, from 1846 to 1851, more than 1 million more Irish immigrated to the United States, 90 percent of whom were Catholic.[40][82]

From 1800 to 1844, Irish emigrants were mainly skilled and economically sufficient Ulster Protestants, including artisans, tradesmen and professionals, and farmers.[83] The Famine and the threat of starvation amongst the Irish Catholic population broke down the psychological barriers that had discouraged them from making the passage to America before. After the second potato blight in 1846, panic over the need to escape their difficult situation in Ireland led many to the belief that "anywhere is better than here". Irish Catholics traveled to England, Canada, and America for new lives. Irish immigration increased dramatically during the period 1845–1849, as ships started transporting Irish emigrants during the autumn and winter periods to meet the demand.[84]

Many of the Famine immigrants to New York City were required quarantine on Staten Island or Blackwell's Island. Weakened by famine and diseases of the poor, who suffered lack of sanitation and crowded shipboard conditions, thousands died from typhoid fever or cholera for reasons directly or indirectly related to the Famine. Doctors did not know how to treat or prevent these.[85]

Despite the small increase in Catholic-Protestant intermarriage following the American Revolutionary War,[65] Catholic-Protestant intermarriage remained uncommon in the United States in the 19th century.[86]

"Scotch-Irish"

Historians have characterized the etymology of the term "Scotch-Irish" as obscure.[87] The term itself is misleading and confusing to the extent that even its usage by authors in historic works of literature about the Scotch-Irish (such as The Mind of the South by W. J. Cash) is often incorrect.[88][89][90] Historians David Hackett Fischer and James G. Leyburn note that usage of the term is unique to North American English and it is rarely used by British historians, or in Ireland or Scotland, where Scots-Irish is a term used by Irish Scottish people to describe themselves.[91][92] The first recorded usage of the term was by Elizabeth I of England in 1573 in reference to Gaelic-speaking Scottish Highlanders who crossed the Irish Sea and intermarried with the Irish Catholic natives of Ireland.[87]

While Protestant immigrants from Ireland in the 18th century were more commonly identified as "Anglo-Irish," and while some preferred to self-identify as "Anglo-Irish,"[91] usage of "Scotch-Irish" in reference to Ulster Protestants who immigrated to the United States in the 18th century likely became common among Episcopalians and Quakers in Pennsylvania, where numerous of these immigrants entered through Philadelphia. Records show that usage of the term with this meaning was made as early as 1757 by Anglo-Irish philosopher Edmund Burke.[93][94]

However, multiple historians have noted that from the time of the American Revolutionary War until 1850, the term largely fell out of usage, because most Ulster Protestants identified as "Irish" until large waves of immigration by Irish Catholics both during and after the 1840s Great Famine in Ireland led those Ulster Protestants in America who lived in proximity to the new immigrants to change their self-identification to "Scotch-Irish,"[list 2] Those Ulster Protestants who did not live in proximity to Irish Catholics continued to self-identify as "Irish" or, as time went on, began to identify as being of "American ancestry."[97]

While those historians note that renewed usage of "Scotch-Irish" after 1850 was motivated by anti-Catholic prejudices among Ulster Protestants,[95][96] considering the historically low rates of intermarriage between Protestants and Catholics in both Ireland and the United States,[list 3] as well as the relative frequency of interethnic and interdenominational marriage amongst Protestants in Ulster,[list 4] and despite the fact that not all Protestant migrants from Ireland historically were of Scottish descent,[56] James G. Leyburn argued for retaining its usage for reasons of utility and preciseness,[104] while historian Wayland F. Dunaway also argued for retention for historical precedent and linguistic description.[105]

During the colonial period, Irish Protestant immigrants settled in the southern Appalachian backcountry and in the Carolina Piedmont.[106] They became the primary cultural group in these areas, and their descendants were in the vanguard of westward movement through Virginia into Tennessee and Kentucky, and thence into Arkansas, Missouri and Texas. By the 19th century, through intermarriage with settlers of English and German ancestry, their descendants lost their identification with Ireland. "This generation of pioneers...was a generation of Americans, not of Englishmen or Germans or Scots-Irish."[107] The two groups had little initial interaction in America, as the 18th-century Ulster immigrants were predominantly Protestant and had become settled largely in upland regions of the American interior, while the huge wave of 19th-century Catholic immigrant families settled primarily in the Northeast and Midwest port cities such as Boston, Philadelphia, New York, Buffalo, or Chicago. However, beginning in the early 19th century, many Irish migrated individually to the interior for work on large-scale infrastructure projects such as canals and, later in the century, railroads.[108]

The Irish Protestants settled mainly in the colonial "back country" of the Appalachian Mountain region, and became the prominent ethnic strain in the culture that developed there.[109] The descendants of Irish Protestant settlers had a great influence on the later culture of the Southern United States in particular and the culture of the United States in general through such contributions as American folk music, country and western music, and stock car racing, which became popular throughout the country in the late 20th century.[110]

Irish immigrants of this period participated in significant numbers in the American Revolution, leading one British Army officer to testify at the House of Commons that "half the rebels (referring to soldiers in the Continental Army) were from Ireland and that half of them spoke Irish."[111] Irish Americans signed the foundational documents of the United States—the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution—and, beginning with Andrew Jackson, served as president.

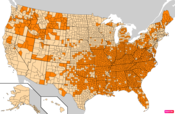

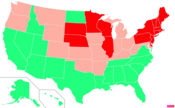

1790 population of Irish origin by state

Estimated Irish American population in the Continental United States as of the 1790 Census.[112]