A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

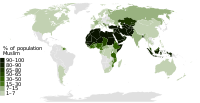

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

Islam in Bulgaria is a minority religion and the second largest religion in the country after Christianity. According to the 2021 Census, the total number of Muslims in Bulgaria stood at 638,708[2] corresponding to 9.8% of the population.[3] Ethnically, Muslims in Bulgaria are Turks, Bulgarians and Roma, living mainly in parts of northeastern Bulgaria (mainly in Razgrad, Targovishte, Shumen and Silistra Provinces) and in the Rhodope Mountains (mainly in Kardzhali Province and Smolyan Province).[2]

History

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1881 | 578,060 | — |

| 1887 | 676,215 | +17.0% |

| 1892 | 643,258 | −4.9% |

| 1900 | 643,300 | +0.0% |

| 1910 | 602,078 | −6.4% |

| 1920 | 690,734 | +14.7% |

| 1926 | 789,296 | +14.3% |

| 1934 | 821,298 | +4.1% |

| 1946 | 938,418 | +14.3% |

| 1992 | 1,110,295 | +18.3% |

| 2001 | 966,978 | −12.9% |

| 2011 | 577,139 | −40.3% |

| 2021 | 638,708 | +10.7% |

| At the 2011 census answering the question for religion was not obligatory. Source: NSI 1881 | ||

Contact with Islam prior to the Ottoman conquest

The first documented Bulgarian contact with the Muslim world was in the early 700s, when Khan Tervel of Bulgaria helped the Byzantines break the Arab siege of Constantinople, after his army reportedly slaid some 22,000 enemy soldiers[4] Two centuries afterwards, enmity turned into mutual collaboration, as Bulgaria under Tsar Simeon I and the Arabs coordinated their attacks on the Byzantine Empire multiple times.[5] During the same period, Bulgarian art started exhibiting some Islamic influence, probably mediated by the Byzantines.[5]

Later on, in the mid 1200s, a group of Seljuk Turks is thought to have settled in North Dobruja.[6] According to Ibn Battuta and Evliya Çelebi, the Turkomans colonised the Black Sea coast between the Bulgarian border and Babadag further north.[7][8][9][10][11] Eventually, part of them returned to Anatolia, while the rest adopted Christianity and are thought to be probable ancestors of the modern Gagauz.[12] However, there is debate whether this settlement ever really happened, as some scholars believe it to have the characteristics of a folk legend.[13]

Scholarly consensus holds that the first Muslim communities in Southeastern Europe, including Bulgaria, appeared in the late fourteenth century, as the peninsula gradually fell under Ottoman rule.[14][15][16]

Ottoman rule (1396–1878)

The Ottoman Empire conquered the last independent piece of the Second Bulgarian Empire, the Tsardom of Vidin, in 1396 (or, as some historians hypothesise, in 1422), and Bulgaria remained under Ottoman and Islamic rule for almost five centuries. Christians in the Ottoman Empire were treated as second-class citizens, i.e., as dhimmis.[17] They were often called giaour, meaning "infidel" as an offensive term.[18] Most of the conquered land was parcelled out to the Sultan's followers, who held it as benefices or fiefs (small ones timar, medium ones zeamet and large ones hass).[19] The system was meant to make the army self-sufficient and to continuously increase the number of Ottoman cavalry soldiers, thus both fueling new conquests and bringing conquered countries under direct Ottoman control.[20]

Christians paid disproportionately higher taxes than Muslims, including the poll tax, jizye, in lieu of military service.[21] According to İnalcık, jizye was the single most important source of income (48 per cent) to the Ottoman budget, with Rumelia accounting for the lion's share, or 81 per cent of the revenues.[22] However, by the early 1600, almost all land had been divided into estates (arpalik) granted to senior Ottoman dignitaries as a form of tax farming, which created conditions for severe exploitation of taxpayers by unscrupulous land holders.[23] According to Radishev, overtaxation became a particularly poignant issue after jizye collection in most of the country was taken over by the Six Divisions of Cavalry.[24]

Bulgarians also paid a number of other taxes, including a tithe ("yushur"), a land tax ("ispench"), a levy on commerce, and various irregularly collected taxes, products and corvees ("avariz"). As a rule, the overall tax burden of the rayah (i.e., Non-Muslims), was twice as high as that of Muslims.[25]

Christians faced a number of other restrictions: they were barred from testifying against Muslims in inter-faith legal disputes.[26] Even though they were free to perform their own religious rituals, this had to be done in a manner that was inconscpicuous to Muslims, i.e., loud prayers or bell ringing were forbidden.[27] They were not permitted to build or repair churches without Muslim consent.[28] They were barred from certain professions, from riding horses, from wearing certain colours or from carrying weapons.[29][30] Their houses and churches could not be taller than Muslim ones.[29][31]

Nevertheless, there were specific categories of rayah who were exempt from nearly all such restrictions, such as the Dervendjis, who guarded important passes, roads, bridges, etc., ore-mining centres such as Chiprovtsi, etc. Some of the most important Bulgarian culutural and economic centres in the 19th century owe their development to a former dervendji status, for example, Gabrovo, Dryanovo, Kalofer, Panagyurishte, Kotel, Zheravna. Similarly, Christians living on wakf holdings were subject to lower tax burden and fewer restrictions.

Probably the worst practice Christian Bulgarians were subjected to was the devşirme, or blood tax, where the healthiest and brightest Christian boys were taken from their families, enslaved, converted to Islam and later employed either in the Janissary military corps or the Ottoman administrative system. The boys were picked from one in forty households.[34] They had to be unmarried and, once taken, were ordered to cut all ties with their family.[35] Christian parents resented the forced recruitment of their children,[36][37] and would beg and seek to buy their children out of the levy. Sources mention different ways to avoid the devshirme such as: marrying the boys at the age of 12, mutilating them or having both father and son convert to Islam.[38] In 1565, the practice led to a revolt in Albania and Epirus, where the inhabitants killed the recruiting officials.[35]

Colonisation and conversion to Islam

Islam in Bulgaria spread through both colonisation with Muslims from Asia Minor and conversion of native Bulgarians. The Ottomans' mass population transfers began in the late 1300s and continued well into the 1500s. Most of these, but far from all, were invountary. The first community settled in present-day Bulgaria was made up of Tatars who willingly arrived to begin a settled life as farmers, the second one a tribe of nomads that had run afoul of the Ottoman administration.[39][40] Both groups settled in the Upper Thracian Plain, in the vicinity of Plovdiv. Another large group of Tatars was moved by Mehmed I to Thrace in 1418, followed by the relocation of more than 1000 Turkoman families to Northeastern Bulgaria in the 1490s.[41][39][42] At the same time, there are records of at least two forced relocations of Bulgarians to Anatolia, one right after the fall of Veliko Tarnovo and a second one to İzmir in the mid-1400s.[43][44] The goal of this "mixing of peoples" was to quell any unrest in the conquered Balkan states, while simultaneously getting rid of troublemakers in the Ottoman backyard in Anatolia.

Nevertheless, the Ottomans never pursued or practiced forced Islamisation of the Bulgarian population, as had earlier been claimed by Communist Bulgarian historiography. According to scholarly consensus, conversion to Islam was voluntary as it offered Bulgarians religious and economic benefits.[45] Missionary activities of the dervish orders resulted in mass conversions to Islam; though many converts retained Christian practices such as baptism, celebration of Christian holidays etc.[46] Muslim population in Bulgaria was a combination of indigenous converts to Islam, and Muslims originating outside the Balkans. Most urban areas gradually became Muslim majority, whereas rural areas remained overwhelmingly Christian.[47] However, in some cases, adopting Islam can be said to be the result of tax coercion. While some authors have argued that other factors, such as desire to retain social status, were of greater importance, Turkish writer Halil İnalcık has referred to the desire to stop paying jizya as a primary incentive for conversion to Islam in the Balkans, and Bulgarian Anton Minkov has argued that it was one among several motivating factors.[48]

Two large-scale studies of the causes of adoption of Islam in Bulgaria, one of the Chepino Valley by Dutch Ottomanist Machiel Kiel, and another one of the region of Gotse Delchev in the Western Rhodopes by Evgeni Radushev reveal a complex set of factors behind the process. These include: pre-existing high population density owing to the late inclusion of the two mountainous regions in the Ottoman system of taxation; immigration of Christian Bulgarians from lowland regions to avoid taxation throughout the 1400s; the relative poverty of the regions; early introduction of local Christian Bulgarians to Islam through contacts with nomadic Yörüks; the nearly constant Ottoman conflict with the Habsburgs from the mid-1500s to the early 1700s; the resulting massive war expenses that led to a sixfold increase in the jizya rate from 1574 to 1691 and the imposition of a war-time avariz tax; the Little Ice Age in the 1600s that caused crop failures and widespread famine; heavy corruption and overtaxation by local landholders—all of which led to a slow, but steady process of Islamisation until the mid-1600s when the tax burden becomes so unbearable that most of the remaining Christians either converted en masse or left for lowland areas.[49][50][51]

As a result of these factors, the population of Ottoman Bulgaria is presumed to have dropped twofold from a peak of approx. 1.8 million (1.2 million Christians and 0.6 million Muslims) in the 1580s to approx. 0.9 million in the 1680s (450,000 Christians and 450,000 Muslims) after growing steadily from a base of approx. 600,000 (450,000 Christians and 150,000 Muslims) in the 1450s.[52]

The Ottoman Empire's greatest advantage compared to other colonial powers, the millet system and the autonomy each denomination had within legal, confessional, cultural and family matters, nevertheless, largely did not apply to Bulgarians and most other Orthodox peoples on the Balkans, as the independent Bulgarian Patriarchate was abolished, and all Bulgarian Orthodox dioceses were subjected to the rule of the Ecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople. Thus, instead of helping Christian Bulgarians maintain their customs and cultural identity, the millet system actually promoted their annihilation. Bulgarian ceased to be a literary language, the higher clergy was invariable Greek, and the Phanariotes started making persistent efforts to hellenise Bulgarians as early as the early 1700s. It was only after the struggle for church autonomy in the mid 1800s and especially after the Bulgarian Exarchate was established by a firman of Sultan Abdülaziz in 1870 that this mistake was corrected.

Post-Independence (1878)

Following the Russo-Turkish War and the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, five sanjaks of the Ottoman Danube Vilayet—Vidin, Veliko Tarnovo, Ruse, Sofia and Varna—were united into the autonomous Principality of Bulgaria, putting Bulgaria again on the political map of Europe after five centuries.[53][54][55] According to the 1875 Ottoman salname, the pre-war Muslim populations of the Principality stood at 405,450 males, or a total of 810,910 people, and accounted for 39.2% of the Principality's population.[56] Most of the Muslims were so-called "Established Muslims", i.e., Turks and Pomaks, but there were also substantial minorities of Circassian and Crimean Tatar Muhacir and Romani.[56]

As a rule, Bulgarian governments after 1878 worked to ensure the freedom of conscience and worship of all non-Bulgarian and non-Christian citizens[57] Thus, Muslims retained the right to administer their schools and houses of worship and kept considerable autonomy in intraconfessional matters such as marriage, divorce and inheritance.[57] Muslims fought in the Serbo-Bulgarian War of 1885 (and all of Bulgaria's subsequent wars except for the Balkan wars and earned widespread respect as well as a high number of medals for bravery in action.[57] Even though there were no ethnic Turkish or Muslim parties, every single national assembly until Bulgaria's occupation by the Soviet Union in 1944 had Turkish and Muslim MPs.[58] Mosques and imams were funded by the state budget.[58]

The Principality expanded somewhat after the Balkan Wars when the largely-Muslim Rhodopes and Western Thrace regions were incorporated into the country. The First Balkan War was accompanied by forced Christianization of Muslim Bulgarians settlements.[59] The atrocious act was repealed immediately by the new government elected after the loss of the Second Balkan War.[57]

Like the practitioners of other beliefs including Orthodox Christians, Muslims suffered under the restriction of religious freedom by the Marxist-Leninist Zhivkov regime which instituted state atheism and suppressed religious communities. The Bulgarian communist regimes declared Islam and other religions to be "opium of the people."[60] In 1989, 310,000[61] to 360,000[62] people fled to Turkey as a result of the communist Zhivkov regime's assimilation campaign;[63] however, 154,937 of them returned in the months after the fall of Zhivkov's regime in November 1989.[64][65][66] The program, which began in 1984, forced all Turks and other Muslims in Bulgaria to adopt Bulgarian names and renounce all Muslim customs.[63] The motivation of the 1984 assimilation campaign was unclear; however, many experts believed that the disproportion between the birth rates of the Turks and the Bulgarians was a major factor.[63] The event became known as "the revival process" or "the renaming." According to Bulgarian historian and human rights activitist Antonina Zhelyazkova, additional 30,000 to 60,000 Muslims emigrated to Turkey between 1990 and 1996 because of the prolonged economic crisis in Bulgaria.[58][62]

Muslims in Bulgaria have enjoyed greater religious freedom after the fall of the Zhivkov regime.[63] New mosques have been built in many cities and villages; one village built a new church and a new mosque side by side.[63] Some villages organized Quran study courses for young people (study of the Quran had been completely forbidden under Zhivkov). Muslims also began publishing their own newspaper, Miusiulmani, in both Bulgarian and Turkish.[63] In 2022, sculptor Vezhdi Rashidov was elected Speaker of the 48th National Assembly, the highest official position ever held by a Muslim in Bulgaria.[67][68][69]

Demographics

According to the 2011 census, there were 638,708 Muslims in Bulgaria, who accounted for 9.8% of the population of the country.[70] According to 2014 estimates, almost one million Muslims live in Bulgaria, forming the largest Muslim minority in any EU country (percentage-wise, not in absolute numbers).[71] According to a 2017 survey by the Pew Research Center, 15% of Bulgaria's population is Muslim.[72] Almost all Muslims in Bulgaria are Bulgarian citizens.[73]

Geographical distribution

According to the 2021 census, 40 out of a total of 266 Bulgarian municipalities had a Muslim majority and three additional municipalities had a Muslim plurality, or one more than in 2011.[74] There were two municipalities with a Muslim population over 90 percent: the Sarnitsa Municipality with a Muslim population of 96.4% and the Chernoochene Municipality with a Muslim population of 90.8%. Practically all municipalities with a Muslim majority are small and very small and generally rural. The exception, and the only provincial capital municipality with a Muslim majority, is the Kardzhali Municipality. All municipalities with a Muslim majority or plurality are listed below.