A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| History of religions |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christianization (or Christianisation) is a term for the specific type of change that occurs when someone or something has been or is being converted to Christianity. Christianization has, for the most part, spread through missions by individual conversions but has also, in some instances, been the result of coercion from governments or military leaders. Christianization is also the term used to designate the conversion of previously non-Christian practices, spaces and places to Christian uses and names. In a third manner, the term has been used to describe the changes that naturally emerge in a nation when sufficient numbers of individuals convert, or when secular leaders require those changes. Christianization of a nation is an ongoing process.[1][2]

It began in the Roman Empire when the early individual followers of Jesus became itinerant preachers in response to the command recorded in Matthew 28:19 (sometimes called the Great Commission) to go to all the nations of the world and preach the good news of the gospel of Jesus.[3] Christianization spread through the Roman Empire and into its surrounding nations in its first three hundred years. The process of Christianizing the Roman Empire was never completed, and Armenia became the first nation to designate Christianity as its state religion in 301.

After 479, Christianization spread through missions north into western Europe. In the High and Late Middle Ages, Christianization was instrumental in the creation of new nations in what became Eastern Europe, and in the spread of literacy there. In the modern era, Christianization became associated with colonialism, which, in an almost equal distribution, missionaries both participated in and opposed. In the post-colonial era, it has produced dramatic growth in China as well as in many former colonial lands in much of Africa. Christianization has become a diverse, pluralist, global phenomenon of the largest religion in the world.

Missions

Historian Dana L. Robert has written that the significant role of Christianization in shaping multiple nations, cultures and societies is understandable only through the concept of Christian mission. Missionaries "go out" among those who have not heard the gospel and preach.[4] Missions, as the primary means of Christianization, are driven by a universalist logic, cannot be equated with western colonialism, but are instead a multi-cultural, often complex, historical process.[4]

David Abulafia and Nóra Berend speak of religious activity in relation to the "frontier" regions at the borders of civilizations. Berend sees a frontier as "a contact zone where an interchange of cultures was constantly taking place".[5] In this way, the missionary religions of Buddhism, Islam and Christianity spread themselves geographically, through teaching and preaching, with interaction sometimes producing conflict, and other times mingling and accommodation.[6]

Alan Neely writes that, "wherever Christianity (or any other faith) is carried from one culture to another, intentionally or not, consciously or not, it is either adapted to that culture or it becomes irrelevant."[6] In his book Christian Mission, Neely provides multiple historical examples of adaptation, accommodation, indigenization, inculturation, autochthonization and contextualization as the means of successful Christianization through missions.[6] Neely's definitions are these:

- Accommodation is a form of adaptation that occurs when the missionary adjusts their own thinking and vocabulary to keep only what is essential and let go of what is expendable in communicating the faith.[7][note 1]

- Indigenization, in this application, refers to taking something that is native to one culture and making it native to another culture; that is, taking Christianity and making it more native by including aspects of native language and practices.[8][9]

- Autochthonization means the same as indigenization, but is specific to Spanish and Portuguese.[8]

- Inculturation, or acculturation, is the gradual process of adopting aspects of Christianity, but it has often mistakenly been seen as socialization to another culture.[10] Changes of dress, customs and names have sometimes been confused with actual Christianization which involves internal and not simply external changes.[11][12] Whenever the gospel has been linked to a particular culture, Gustavo Gutiérrez forcefully insists the result has been subjugation not conversion.[13]

- Contextualization is a way to be faithful to the essence of the message while also being relevant to the people to whom it is being presented.[14] In the 21st century, contextualization has led missions to build daycare centers, wells for clean water, schools, address housing and economic injustice issues and more.[13][15][16] It depends on the people being addressed, as well as "geography, language, ethnicity, political and economic systems, class gender and age, time frame, sense of identity, religion, values and history".[17]

Individual conversion

James P. Hanigan writes that individual conversion is the foundational experience and the central message of Christianization, adding that Christian conversion begins with an experience of being "thrown off balance" through cognitive and psychological "disequilibrium", followed by an "awakening" of consciousness and a new awareness of God.[18] Hanigan compares it to "death and rebirth, a turning away..., a putting off of the old..., a change of mind and heart".[12] The person responds by acknowledging and confessing personal lostness and sinfulness, and then accepting a call to holiness thus restoring balance. This initial internal conversion is only the beginning of Christianization; it is followed by practices that further the process of Christianizing the individual's lifestyle, which according to Hanigan, will include ethical changes.[19]

While Christian theologians such as the fourth century Augustine and the ninth century Alcuin maintained that conversion must be voluntary,[20][21] there are historical examples of coercion in conversion. Constantine used both law and force to eradicate the practice of sacrifice and repress heresy though not specifically to promote conversion.[22][23] Theodosius also wrote laws to eliminate heresies, but made no requirement for pagans or Jews to convert to Christianity.[24][25][26] However, the sixth century Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I and the seventh century emperor Heraclius attempted to force cultural and religious uniformity by requiring baptism of the Jews.[27][28][29][30] In 612, the Visigothic King Sisebut, prompted by Heraclius, declared the obligatory conversion of all Jews in Spain.[31] In the many new nation-states being formed in Eastern Europe of the Late Middle Ages, some kings and princes pressured their people to adopt the new religion.[32] And in the Northern crusades, the fighting princes obtained widespread conversion through political pressure or military coercion.[33]

Baptism

Jesus began his ministry after his baptism by John the Baptist which can be dated to approximately AD 28–35 based on references by the Jewish historian Josephus in his (Antiquities 18.5.2).[34][35]

Individual conversion is followed by the initiation rite of baptism.[36] In Christianity's earliest communities, candidates for baptism were introduced by someone willing to stand surety for their character and conduct. Baptism created a set of responsibilities within the Christian community.[37] Candidates for baptism were instructed in the major tenets of the faith, examined for moral living, sat separately in worship, were not yet allowed to receive the communion eucharist, but were still generally expected to demonstrate commitment to the community, and obedience to Christ's commands, before being accepted into the community as a full member. This could take months to years.[38]

The normal practice in the ancient church was baptism by immersion of the whole head and body of an adult, with the exception of infants in danger of death, until the fifth or sixth century.[39] Historian Philip Schaff has written that sprinkling, or pouring of water on the head of a sick or dying person, where immersion was impractical, was also practiced in ancient times and up through the twelfth century.[40] Infant baptism was controversial for the Protestant Reformers, but according to Schaff, it was practiced by the ancients and is neither required nor forbidden in the New Testament.[41]

Eucharist

The celebration of the eucharist (also called communion) was the common unifier for early Christian communities, and remains one of the most important of Christian rituals. Early Christians believed the Christian message, the celebration of communion (the Eucharist) and the rite of baptism came directly from Jesus of Nazareth.[42]

Father Enrico Mazza writes that the "Eucharist is an imitation of the Last Supper" when Jesus gathered his followers for their last meal together the night before he was arrested and killed.[43] While the majority share the view of Mazza, there are others such as New Testament scholar Bruce Chilton who argue that there were multiple origins of the Eucharist.[44][45]

In the Middle Ages, the Eucharist came to be understood as a sacrament (wherein God is present) that evidenced Christ's sacrifice, and the prayer given with the rite was to include two strophes of thanksgiving and one of petition. The prayer later developed into the modern version of a narrative, a memorial to Christ and an invocation of the Holy Spirit.[43]

Confirmation

In the early 1500s, confirmation was added to the rites of initiation.[46] While baptism, instruction, and Eucharist have remained the essential elements of initiation in all Christian communities, theologian Knut Alfsvåg writes on the differing status of confirmation in different denominations:

Some see baptism, confirmation, and first communion as different elements in a unified rite through which one becomes a part of the Christian church. Others consider confirmation a separate rite which may or may not be considered a condition for becoming a fully accepted member of the church in the sense that one is invited to take part in the celebration of the Eucharist. Among those who see confirmation as a separate rite some see it as a sacrament, while others consider it a combination of intercessory prayer and graduation ceremony after a period of instruction.[46]

Places and practices

Christianization has at times involved appropriation, removal and/or redesignation of aspects of native religion and former sacred spaces. This was allowed, or required, or sometimes forbidden by the missionaries involved.[47] The church adapts to its local cultural context, just as local culture and places are adapted to the church, or in other words, Christianization has always worked in both directions: Christianity absorbs from native culture as it is absorbed into it.[48][49]

When Christianity spread beyond Judaea, it first arrived in Jewish diaspora communities.[50] The Christian church was modeled on the synagogue, and Christian philosophers synthesized their Christian views with Semitic monotheism and Greek thought.[51][52] The Latin church adopted aspects of Platonic thought and used the Latin names for months and weekdays that etymologically derived from Roman mythology.[53][54]

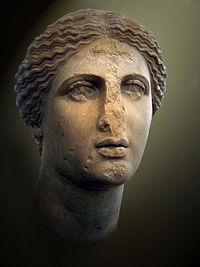

Christian art in the catacombs beneath Rome rose out of a reinterpretation of Jewish and pagan symbolism.[55][56] While many new subjects appear for the first time in the Christian catacombs - i.e. the Good Shepherd, Baptism, and the Eucharistic meal – the Orant figures (women praying with upraised hands) probably came directly from pagan art.[57][58][note 2]

Bruce David Forbes says "Some way or another, Christmas was started to compete with rival Roman religions, or to co-opt the winter celebrations as a way to spread Christianity, or to baptize the winter festivals with Christian meaning in an effort to limit their excesses. Most likely all three".[60] Michelle Salzman has shown that, in the process of converting the Roman Empire's aristocracy, Christianity absorbed the values of that aristocracy.[61]

Some scholars have suggested that characteristics of some pagan gods — or at least their roles — were transferred to Christian saints after the fourth century.[62] Demetrius of Thessaloniki became venerated as the patron of agriculture during the Middle Ages. According to historian Hans Kloft, that was because the Eleusinian Mysteries, Demeter's cult, ended in the 4th century, and the Greek rural population gradually transferred her rites and roles onto the Christian saint.[62]

Several early Christian writers, including Justin (2nd century), Tertullian, and Origen (3rd century) wrote of Mithraists copying Christian beliefs and practices yet remaining pagan.[63]

In both Jewish and Roman tradition, genetic families were buried together, but an important cultural shift took place in the way Christians buried one another: they gathered unrelated Christians into a common burial space, as if they really were one family, "commemorated them with homogeneous memorials and expanded the commemorative audience to the entire local community of coreligionists" thereby redefining the concept of family.[64][65]

Temple conversion within Roman Empire

R. P. C. Hanson says the direct conversion of temples into churches began in the mid-fifth century but only in a few isolated incidents.[66][note 3] According to modern archaeology, of the thousands of temples that existed across the empire, 120 pagan temples were converted to churches with the majority dated after the fifth century. It is likely this stems from the fact that these buildings remained officially in public use, ownership could only be transferred by the emperor, and temples remained protected by law.[68][69][70][71]

In the fourth century, there were no conversions of temples in the city of Rome itself.[72] It is only with the formation of the Papal State in the eighth century, (when the emperor's properties in the West came into the possession of the bishop of Rome), that the conversions of temples in Rome took off in earnest.[73]

According to Dutch historian Feyo L. Schuddeboom, individual temples and temple sites in the city of Rome were converted to churches primarily to preserve their exceptional architecture. They were also used pragmatically because of the importance of their location at the center of town.[68]

Temple and icon destruction

During his long reign (307 - 337), Constantine (the first Christian emperor) both destroyed and built a few temples, plundered more, and generally neglected the rest.[74]

In the 300 years prior to the reign of Constantine, Roman authority had confiscated various church properties. For example, Christian historians recorded that Hadrian (2nd century), when in the military colony of Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem), had constructed a temple to Aphrodite on the site of the crucifixion of Jesus on Golgotha hill in order to suppress veneration there.[75] Constantine was vigorous in reclaiming such properties whenever these issues were brought to his attention, and he used reclamation to justify the destruction of Aphrodite's temple. Using the vocabulary of reclamation, Constantine acquired several more sites of Christian significance in the Holy Land.[76][77]

In Eusebius' church history, there is a bold claim of a Constantinian campaign to destroy the temples, however, there are discrepancies in the evidence.[78] Temple destruction is attested to in 43 cases in the written sources, but only four have been confirmed by archaeological evidence.[79][note 4] Historians Frank R. Trombley and Ramsay MacMullen explain that discrepancies between literary sources and archaeological evidence exist because it is common for details in the literary sources to be ambiguous and unclear.[84] For example, Malalas claimed Constantine destroyed all the temples, then he said Theodisius destroyed them all, then he said Constantine converted them all to churches.[85][86][note 5]

Additional calculated acts of desecration – removing the hands and feet or mutilating heads and genitals of statues, and "purging sacred precincts with fire" – were acts committed by the common people during the early centuries.[note 6] While seen as 'proving' the impotence of the gods, pagan icons were also seen as having been "polluted" by the practice of sacrifice. They were, therefore, in need of "desacralization" or "deconsecration".[100] Antique historian Peter Brown says that, while it was in some ways studiously vindictive, it was not indiscriminate or extensive.[101][102] Once temples, icons or statues were detached from 'the contagion' of sacrifice, they were seen as having returned to innocence. Many statues and temples were then preserved as art.[101] Professor of Byzantine history Helen Saradi-Mendelovici writes that this process implies appreciation of antique art and a conscious desire to find a way to include it in Christian culture.[103]

Aspects of paganism remained part of the civic culture of the Roman Empire till its end. Public spectacles were popular and resisted Christianization: gladiatorial combats (munera), animal hunts (venationes), theatrical performances (ludi scaenici), and chariot races (ludi circenses) were accommodated by Roman society even while that society disagreed and debated the definition and scope of christianization.[104] Historian of antiquity Richard Lim writes that it was within this process of debate that "the category of the secular was developed ... helped buffer select cultural practices, including Roman spectacles, from the claims of those who advocated a more thorough christianization of Roman society."[23] This produced a vigorous public culture shared by polytheists, Jews and Christians alike.[105][note 7]

The Roman Empire cannot be considered Christianized before Justinian I in the sixth century, though most scholars agree the Empire was never fully Christianized.[105][1] Archaeologist and historian Judith Herrin has written in her article on "Book Burning as Purification" that under Justinian, there was considerable destruction.[109] The decree of 528 barred pagans from state office when, decades later, Justinian ordered a "persecution of surviving Hellenes, accompanied by the burning of pagan books, pictures and statues". This took place at the Kynêgion.[109] Herrin says it is difficult to assess the degree to which Christians are responsible for the losses of ancient documents in many cases, but in the mid-sixth century, active persecution in Constantinople destroyed many ancient texts.[109]

Other sacred sites

The "Venerable Bede" was a Christian monk (672 - 735) who wrote what sociologist and anthropologist Hutton Webster describes as "the first truly historical work by an Englishman" describing the Christianization of Britain.[110] Pope Gregory I had sent Augustine and several helpers as missionaries to Kent and its powerful King Ethelbert.[111] One of those helpers, Abbott Mellitus, received this letter from Gregory on the proper methods for converting the local people.

I think that the temples of the idols in that nation ought not to be destroyed; but let the idols that are in them be destroyed; let holy water be made and sprinkled in the said temples, and let altars be erected and relics placed. For if those temples are well built, it is requisite that they be converted from the worship of devils to the service of the true God; that the people, seeing that their temples are not destroyed, may remove error from their hearts, and, knowing and adoring the true God, may the more familiarly resort to the places to which they have become accustomed.[112][113]

When Benedict moved to Monte Cassino about 530, a small temple with a sacred grove and a separate altar to Apollo stood on the hill. The population was still mostly pagan. The land was most likely granted as a gift to Benedict from one of his supporters. This would explain the authoritative way he immediately cut down the groves, removed the altar, and built an oratory before the locals were converted.[114]

Christianization of the Irish landscape was a complex process that varied considerably depending on local conditions.[115] Ancient sites were viewed with veneration, and were excluded or included for Christian use based largely on diverse local feeling about their nature, character, ethos and even location.[116]

In Greece, Byzantine scholar Alison Frantz has won consensus support of her view that, aside from a few rare instances such as the Parthenon which was converted to a church in the sixth century, temple conversions (including the Erechtheion and the Theseion) took place in and after the seventh century, after the displacements caused by the Slavic invasions.[117]

In early Anglo-Saxon England, non-stop religious development meant paganism and Christianity were never completely separate.[118] Archaeologist Lorcan Harney has reported that Anglo-Saxon churches were built by pagan barrows after the 11th century.[119] Richard A. Fletcher suggests that, within the British Isles and other areas of northern Europe that were formerly druidic, there are a dense number of holy wells and holy springs that are now attributed to a saint, often a highly local saint, unknown elsewhere.[120][121] In earlier times many of these were seen as guarded by supernatural forces such as the melusina, and many such pre-Christian holy wells appear to have survived as baptistries.[122] According to Willibald's Life of Saint Boniface, about 723, the missioner Boniface cut down the sacred Donar's Oak also called the 'Oak of Jupiter' and used the lumber to build a church dedicated to St. Peter.[123][124]

By 771, Charlemagne had inherited the long established conflict with the Saxons who regularly specifically targeted churches and monasteries in brutal raids into Frankish territory.[125] In January 772, Charlemagne retaliated with an attack on the Saxon's most important holy site, a sacred grove in southern Engria.[126] "It was dominated by the Irminsul ('Great Pillar'), which was either a (wooden) pillar or an ancient tree and presumably symbolized Germanic religion's 'Universal Tree'. The Franks cut down the Irminsul, looted the accumulated sacrificial treasures (which the King distributed among his men), and torched the entire grove... Charlemagne ordered a Frankish fortress to be erected at the Eresburg".[127]

Early historians of Scandinavian Christianization wrote of dramatic events associated with Christianization in the manner of political propagandists according to John Kousgärd Sørensen who references the 1987 survey by the historian of medieval Scandinavia, Birgit Sawyer.[128] Sørensen focuses on the changes of names, both personal and place names, showing that cultic elements were not banned and are still in evidence today.[129] Large numbers of pre-Christian names survive into the present day, and Sørensen says this demonstrates the process of Christianization in Denmark was peaceful and gradual and did not include the complete eradication of the old cultic associations.[130] However, there are local differences.[131]

Outside of Scandinavia, old names did not fare as well.[132]

The highest point in Paris was known in the pre-Christian period as the Hill of Mercury, Mons Mercuri. Evidence of the worship of this Roman god here was removed in the early Christian period and in the ninth century a sanctuary was built here, dedicated to the 10000 martyrs. The hill was then called Mons Martyrum, the name by which it is still known (Mont Martres) (Longnon 1923, 377; Vincent 1937, 307). Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Christianization

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk