A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

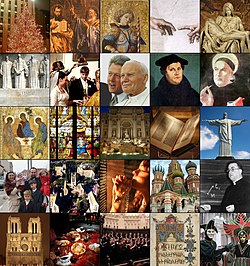

| Christian culture |

|---|

|

| Christianity portal |

Christianity has been intricately intertwined with the history and formation of Western society. Throughout its long history, the Church has been a major source of social services like schooling and medical care; an inspiration for art, culture and philosophy; and an influential player in politics and religion. In various ways it has sought to affect Western attitudes towards vice and virtue in diverse fields. Festivals like Easter and Christmas are marked as public holidays; the Gregorian Calendar has been adopted internationally as the civil calendar; and the calendar itself is measured from an estimation of the date of Jesus's birth.

The cultural influence of the Church has been vast. Church scholars preserved literacy in Western Europe following the Fall of the Western Roman Empire.[1] During the Middle Ages, the Church rose to replace the Roman Empire as the unifying force in Europe. The medieval cathedrals remain among the most iconic architectural feats produced by Western civilization. Many of Europe's universities were also founded by the church at that time. Many historians state that universities and cathedral schools were a continuation of the interest in learning promoted by monasteries.[2] The university is generally regarded[3][4] as an institution that has its origin in the Medieval Christian setting, born from Cathedral schools.[5] Many scholars and historians attribute Christianity to having contributed to the rise of the Scientific Revolution.[6][7]

The Reformation brought an end to religious unity in the West, but the Renaissance masterpieces produced by Catholic artists like Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael remain among the most celebrated works of art ever produced. Similarly, Christian sacred music by composers like Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Handel, Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Liszt, and Verdi is among the most admired classical music in the Western canon.

The Bible and Christian theology have also strongly influenced Western philosophers and political activists.[8] The teachings of Jesus, such as the Parable of the Good Samaritan, are argued by some to be among the most important sources of modern notions of "human rights" and the welfare commonly provided by governments in the West. Long-held Christian teachings on sexuality, marriage, and family life have also been influential and controversial in recent times.[9]: 309 Christianity in general affected the status of women by condemning marital infidelity, divorce, incest, polygamy, birth control, infanticide (female infants were more likely to be killed), and abortion.[10]: 104 While official Catholic Church teaching[11]: 61 considers women and men to be complementary (equal and different), some modern "advocates of ordination of women and other feminists" argue that teachings attributed to St. Paul and those of the Fathers of the Church and Scholastic theologians advanced the notion of a divinely ordained female inferiority.[12] Nevertheless, women have played prominent roles in Western history through and as part of the church, particularly in education and healthcare, but also as influential theologians and mystics.

Christians have made a myriad of contributions to human progress in a broad and diverse range of fields, both historically and in modern times, including science and technology,[13][14][15][16][17] medicine,[18] fine arts and architecture,[19][20][21] politics, literatures,[21] music,[21] philanthropy, philosophy,[22][23][24]: 15 ethics,[25] humanism,[26][27][28] theatre and business.[29][30][20][31] According to 100 Years of Nobel Prizes a review of Nobel prizes award between 1901 and 2000 reveals that (65.4%) of Nobel Prizes Laureates, have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference.[32] Eastern Christians (particularly Nestorian Christians) have also contributed to the Arab Islamic Civilization during the Ummayad and the Abbasid periods by translating works of Greek philosophers to Syriac and afterwards to Arabic.[33][34][35] They also excelled in philosophy, science, theology and medicine.[36][37]

Rodney Stark writes that medieval Europe's advances in production methods, navigation, and war technology "can be traced to the unique Christian conviction that progress was a God-given obligation, entailed in the gift of reason. That new technologies and techniques would always be forthcoming was a fundamental article of Christian faith. Hence, no bishops or theologians denounced clocks or sailing ships—although both were condemned on religious grounds in various non-Western societies."[38][example needed]

Christianity contributed greatly to the development of European cultural identity,[39] although some progress originated elsewhere, Romanticism began with the curiosity and passion of the pagan world of old.[40][41] Outside the Western world, Christianity has had an influence and contributed to various cultures, such as in Africa, Central Asia, the Near East, Middle East, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.[42][43] Scholars and intellectuals have noted Christians have made significant contributions to Arab and Islamic civilization since the introduction of Islam.[44]

Politics and law

From early persecution to state religion

The foundation of canon law is found in its earliest texts and their interpretation in the church fathers' writings. Christianity began as a Jewish sect in the mid-1st century arising out of the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. The life of Jesus is recounted in the New Testament of the Bible, one of the bedrock texts of Western Civilization and inspiration for countless works of Western art.[45] Jesus' birth is commemorated in the festival of Christmas, his death during the Paschal Triduum, and his resurrection during Easter. Christmas and Easter remain holidays in many Western nations.

Jesus learned the texts of the Hebrew Bible, with its Ten Commandments (which later became influential in Western law [citation needed]) and became an influential wandering preacher. He was a persuasive teller of parables and moral philosopher who urged followers to worship God, act without violence or prejudice, and care for the sick, hungry, and poor. These teachings deeply influenced Western culture. Jesus criticized the hypocrisy of the religious establishment, which drew the ire of the authorities, who persuaded the Roman Governor of the province of Judaea, Pontius Pilate, to have him executed. The Talmud says Jesus was executed by the Hasmonean government who stone and hang him and that his punishment is to boil in human excrements for eternity for sorcery and for leading the people into apostasy.[46] In Jerusalem, around 30AD, Jesus was crucified.[47]

The early followers of Jesus, including Saints Paul and Peter carried this new theology concerning Jesus and its ethic throughout the Roman Empire and beyond, sowing the seeds for the development of the Catholic Church, of which Saint Peter is considered the first Pope. Christians sometimes faced persecution during these early centuries, particularly for their refusal to join in worshiping the emperors. Nevertheless, carried through the synagogues, merchants and missionaries across the known world, Christianity quickly grew in size and influence.[47] Its unique appeal was partly the result of its values and ethics.[48]

The Bible has had a profound influence on Western civilization and on cultures around the globe; it has contributed to the formation of Western law, art, texts, and education.[49][50] With a literary tradition spanning two millennia, the Bible is one of the most influential works ever written. From practices of personal hygiene to philosophy and ethics, the Bible has directly and indirectly influenced politics and law, war and peace, sexual morals, marriage and family life, toilet etiquette, letters and learning, the arts, economics, social justice, medical care and more.[51]

Human value as a foundation to law

The world's first civilizations were Mesopotamian sacred states ruled in the name of a divinity or by rulers who were seen as divine. Rulers, and the priests, soldiers and bureaucrats who carried out their will, were a small minority who kept power by exploiting the many.[52]

If we turn to the roots of our western tradition, we find that in Greek and Roman times not all human life was regarded as inviolable and worthy of protection. Slaves and 'barbarians' did not have a full right to life and human sacrifices and gladiatorial combat were acceptable... Spartan Law required that deformed infants be put to death; for Plato, infanticide is one of the regular institutions of the ideal State; Aristotle regards abortion as a desirable option; and the Stoic philosopher Seneca writes unapologetically: "Unnatural progeny we destroy; we drown even children who at birth are weakly and abnormal... And whilst there were deviations from these views..., it is probably correct to say that such practices...were less proscribed in ancient times. Most historians of western morals agree that the rise of ...Christianity contributed greatly to the general feeling that human life is valuable and worthy of respect.[53]

W.E.H.Lecky gives the now classical account of the sanctity of human life in his history of European morals saying Christianity "formed a new standard, higher than any which then existed in the world...".[54] Christian ethicist David P. Gushee says "The justice teachings of Jesus are closely related to a commitment to life's sanctity...".[55]

John Keown, a professor of Christian ethics distinguishes this 'sanctity of life' doctrine from "a quality of life approach, which recognizes only instrumental value in human life, and a vitalistic approach, which regards life as an absolute moral value... sanctity of life approach ... which embeds a presumption in favor of preserving life, but concedes that there are circumstances in which life should not be preserved at all costs", and it is this which provides the solid foundation for law concerning end of life issues.[56]

Early legal views of women

Rome had a social caste system, with women having "no legal independence and no independent property".[57] Early Christianity, as Pliny the Younger explains in his letters to Emperor Trajan, had people from "every age and rank, and both sexes".[58] Pliny reports arresting two slave women who claimed to be 'deaconesses' in the first decade of the second century.[59] There was a rite for the ordination of women deacons in the Roman Pontifical (a liturgical book) up through the 12th century. For women deacons, the oldest rite in the West comes from an eighth-century book, whereas Eastern rites go back to the third century and there are more of them.[60]

The New Testament refers to a number of women in Jesus' inner circle. There are several Gospel accounts of Jesus imparting important teachings to and about women: his meeting with the Samaritan woman at the well, his anointing by Mary of Bethany, his public admiration for a poor widow who donated two copper coins to the Temple in Jerusalem, his stepping to the aid of the woman accused of adultery, his friendship with Mary and Martha the sisters of Lazarus, and the presence of Mary Magdalene, his mother, and the other women as he was crucified. Historian Geoffrey Blainey concludes that "as the standing of women was not high in Palestine, Jesus' kindnesses towards them were not always approved by those who strictly upheld tradition".[61]

According to Christian apologist Tim Keller, it was common in the Greco-Roman world to expose female infants because of the low status of women in society. The church forbade its members to do so. Greco-Roman society saw no value in an unmarried woman, and therefore it was illegal for a widow to go more than two years without remarrying. Christianity did not force widows to marry and supported them financially. Pagan widows lost all control of their husband's estate when they remarried, but the church allowed widows to maintain their husband's estate. Christians did not believe in cohabitation. If a Christian man wanted to live with a woman, the church required marriage, and this gave women legal rights and far greater security. Finally, the pagan double standard of allowing married men to have extramarital sex and mistresses was forbidden. Jesus' teachings on divorce and Paul's advocacy of monogamy began the process of elevating the status of women so that Christian women tended to enjoy greater security and equality than women in surrounding cultures.[62]

Laws affecting children

In the ancient world, infanticide was not legal but was rarely prosecuted. A broad distinction was popularly made between infanticide and infant exposure, which was widely practiced. Many exposed children died, but many were taken by speculators who raised them to be slaves or prostitutes. It is not possible to ascertain, with any degree of accuracy, what diminution of infanticide resulted from legal efforts against it in the Roman empire. "It may, however, be safely asserted that the publicity of the trade in exposed children became impossible under the influence of Christianity, and that the sense of the seriousness of the crime was very considerably increased."[54]: 31, 32

Legal status under Constantine

Emperor Constantine's Edict of Milan in 313 AD ended the state-sponsored persecution of Christians in the East, and his own conversion to Christianity was a significant turning point in history.[63] In 312, Constantine offered civic toleration to Christians, and through his reign instigated laws and policies in keeping with Christian principles – making Sunday the Sabbath "day of rest" for Roman society (though initially this was only for urban dwellers) and embarking on a church building program. In AD 325, Constantine conferred the First Council of Nicaea to gain consensus and unity within Christianity, with a view to establishing it as the religion of the Empire. The population and wealth of the Roman Empire had been shifting east, and around the year 330, Constantine established the city of Constantinople as a new imperial city which would be the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Eastern Patriarch in Constantinople now came to rival the Pope in Rome. Although cultural continuity and interchange would continue between these Eastern and Western Roman Empires, the history of Christianity and Western culture took divergent routes, with a final Great Schism separating Roman and Eastern Christianity in 1054 AD.

Fourth century political influence and laws against pagans

During the fourth century, Christian writing and theology blossomed into a "Golden Age" of literary and scholarly activity unmatched since the days of Virgil and Horace. Many of these works remain influential in politics, law, ethics and other fields. A new genre of literature was also born in the fourth century: church history.[64][65]

The remarkable transformation of Christianity from peripheral sect to major force within the Empire is often held to be a result of the influence held by St. Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan, but this is unlikely.[66]: 60, 63, 131 In April of 390, the Emperor Theodosius I ordered the punitive massacre of thousands of the citizens of Thessaloniki. In a private letter from Ambrose to Theodosius, sometime in August after this event, Ambrose told Theodosius he cannot be given communion while Theodosius is unrepentant of this terrible act.[67]: 12 [68][69] Wolf Liebeschuetz says records show "Theodosius duly complied and came to church humbly, without his imperial robes, until Christmas, when Ambrose openly readmitted him to communion."[70]: 262

McLynn states that "the encounter at the church door has long been known as a pious fiction."[71]: 291 Daniel Washburn explains that the image of the mitered prelate braced in the door of the cathedral in Milan blocking Theodosius from entering, is a product of the imagination of Theodoret, a historian of the fifth century who wrote of the events of 390 "using his own ideology to fill the gaps in the historical record."[72]: 215 According to Peter Brown, these events concern personal piety; they do not represent a turning point in history with the State submitting to the Church.[73]: 111 [66]: 63, 64

According to Christian literature of the fourth century, paganism ended by the early to mid—fifth century with everyone either converted or cowed.[74]: 633, 640 Contemporary archaeology, on the other hand, indicates this is not so; paganism continued across the empire, and the end of paganism varied from place to place.[75]: 54 Violence such as temple destructions are attested in some locations, generally in small numbers, and are not spread equally throughout the empire. In most regions away from the imperial court, the end of paganism was, more often, gradual and untraumatic.[75]: 156, 221 [76]: 5, 7, 41

Theodosius reigned (albeit for a brief interim) as the last Emperor of a united Eastern and Western Roman Empire. Between 389 and 391, Theodosius promulgated the Theodosian Decrees, a collection of laws from the time of Constantine including laws against heretics and pagans. In 391 Theodosius blocked the restoration of the pagan Altar of Victory to the Roman Senate and then fought against Eugenius, who courted pagan support for his own bid for the imperial throne.[77] Brown says the language of the Theodosian Decrees is "uniformly vehement and the penalties are harsh and frequently horrifying." They may have provided a foundation for similar laws in the High Middle Ages.[74]: 638 However, in antiquity, these laws were not much enforced, and Brown adds that, "In most areas, polytheists were not molested, and, apart from a few ugly incidents of local violence, Jewish communities also enjoyed a century of stable, even privileged, existence."[78]: 643 Contemporary scholars indicate pagans were not wiped out or fully converted by the fifth century as Christian sources claim. Pagans remained throughout the fourth and fifth centuries in sufficient numbers to preserve a broad spectrum of pagan practices into the 6th century and even beyond in some places.[79]: 19

The political and legal impact of the fall of Rome

The central bureaucracy of imperial Rome remained in Rome in the sixth century but was replaced in the rest of the empire by German tribal organization and the church.[80]: 67 After the fall of Rome (476) most of the west returned to a subsistence agrarian form of life. What little security there was in this world was largely provided by the Christian church.[81][82] The papacy served as a source of authority and continuity at this critical time. In the absence of a magister militum living in Rome, even the control of military matters fell to the pope.

The role of Christianity in politics and law in the Medieval period

The historian Geoffrey Blainey likened the Catholic Church in its activities during the Middle Ages to an early version of a welfare state: "It conducted hospitals for the old and orphanages for the young; hospices for the sick of all ages; places for the lepers; and hostels or inns where pilgrims could buy a cheap bed and meal". It supplied food to the population during famine and distributed food to the poor. This welfare system the church funded through collecting taxes on a large scale and by owning large farmlands and estates.[83] The canon law of the Catholic Church (Latin: jus canonicum)[84] is the system of laws and legal principles made and enforced by the hierarchical authorities of the Church to regulate its external organization and government and to order and direct the activities of Catholics toward the mission of the Church.[85] It was the first modern Western legal system[86] and is the oldest continuously functioning legal system in the West,[87] predating the European common law and civil law traditions.

The Rule of Benedict as a legal base in the Dark Ages

The period between the Fall of Rome (476 C.E.) and the rise of the Carolingian Franks (750 C.E.) is often referred to as the "Dark Ages", however, it could also be designated the "Age of the Monk". This era had a lasting impact on politics and law through Christian aesthetes like St. Benedict (480–543), who vowed a life of chastity, obedience and poverty; after rigorous intellectual training and self-denial, Benedictines lived by the "Rule of Benedict:" work and pray. This "Rule" became the foundation of the majority of the thousands of monasteries that spread across what is modern day Europe; "...certainly there will be no demur in recognizing that St. Benedict's Rule has been one of the great facts in the history of western Europe, and that its influence and effects are with us to this day."[81]: intro.

Monasteries were models of productivity and economic resourcefulness teaching their local communities animal husbandry, cheese making, wine making, and various other skills.[88] They were havens for the poor, hospitals, hospices for the dying, and schools. Medical practice was highly important in medieval monasteries, and they are best known for their contributions to medical tradition. They also made advances in sciences such as astronomy.[89] For centuries, nearly all secular leaders were trained by monks because, excepting private tutors who were still, often, monks, it was the only education available.[90]

The formation of these organized bodies of believers distinct from political and familial authority, especially for women, gradually carved out a series of social spaces with some amount of independence thereby revolutionizing social history.[91]

Gregory the Great (c 540–604) administered the church with strict reform. A trained Roman lawyer, administrator, and monk, he represents the shift from the classical to the medieval outlook and was a father of many of the structures of the later Catholic Church. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, he looked upon Church and State as co-operating to form a united whole, which acted in two distinct spheres, ecclesiastical and secular, but by the time of his death, the papacy was the great power in Italy:[92] Gregory was one of the few sovereigns called Great by universal consent. He is known for sending out the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome to convert the then-pagan Anglo-Saxons in England, for his many writings, his administrative skills, and his focus on the welfare of the people.[93][94] He also fought the Arian heresy and the Donatists, pacified the Goths, left a famous example of penitence for a crime, revised the liturgy, and influenced music through the development of antiphonal chants.[95]

Pope Gregory the Great made himself in Italy a power stronger than emperor or exarch, and established a political influence which dominated the peninsula for centuries. From this time forth the varied populations of Italy looked to the pope for guidance, and Rome as the papal capital continued to be the centre of the Christian world.

Charlemagne transformed law and founded feudalism in the Early Middle Ages

Charlemagne ("Charles the Great" in English) became king of the Franks in 768. He conquered the Low Countries, Saxony, and northern and central Italy, and in 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor. Sometimes called the "Father of Europe" and the founder of feudalism, Charlemagne instituted political and judicial reform and led what is sometimes referred to as the Early Renaissance or the Christian Renaissance.[96] Johannes Fried writes that Charlemagne left such a profound impression on his age that traces of it still remain. He promoted education and literacy and subsidized schools, he worked at protecting the poor enacting economic and currency reform; these, along with legal and judicial reforms, created a more lawful and prosperous kingdom. This helped form a group of independent minded warlords into a well-administered empire, with a tradition of working with the Pope, which became the precursor to the nation of France.[97] Fried says, "he was the first king and emperor to seriously enact the legal principle according to which the Pope was beyond the reach of all human justice—a decision that would have major ramifications in the future."[97]: 12

Modern common law, persecution, and secularization began in the High Middle Ages

By the late 11th century, beginning with the efforts of Pope Gregory VII, the Church successfully established itself as "an autonomous legal and political ... within Western Christendom".[98]: 23 For the next three hundred years, the Church held great influence over Western society;[98]: 23 church laws were the single "universal law ... common to jurisdictions and peoples throughout Europe."[98]: 30 With its own court system, the Church retained jurisdiction over many aspects of ordinary life, including education, inheritance, oral promises, oaths, moral crimes, and marriage.[98]: 31 As one of the more powerful institutions of the Middle Ages, Church attitudes were reflected in many secular laws of the time.[99]: 1 The Catholic Church was very powerful, essentially internationalist and democratic in it structures, with its many branches run by the different monastic organizations, each with its own distinct theology and often in disagreement with the others.[100]: 311, 312 [101]: 396

Men of a scholarly bent usually took Holy Orders and frequently joined religious institutes. Those with intellectual, administrative, or diplomatic skill could advance beyond the usual restraints of society. Leading churchmen from faraway lands were accepted in local bishoprics, linking European thought across wide distances. Complexes like the Abbey of Cluny became vibrant centres with dependencies spread throughout Europe. Ordinary people also trekked vast distances on pilgrimages to express their piety and pray at the site of holy relics.[102]

In the pivotal twelfth century (1100s), Europe began laying the foundation for its gradual transformation from the medieval to the modern.[103]: 154 Feudal lords slowly lost power to the feudal kings as kings began centralizing power into themselves and their nation-state. Kings built their own armies instead of relying on their vassals, thereby taking power from the nobility. The 'state' took over legal practices that had traditionally belonged to local nobles and local church officials; and they began to target minorities.[103]: 4, 5 [104]: 209 According to R.I. Moore and other contemporary scholars, "the growth of secular power and the pursuit of secular interests, constituted the essential context of the developments that led to a persecuting society."[103]: 4, 5 [105]: 8–10 [106]: 224 [107]: xviii This has had a permanent impact on politics and law in multiple ways: through a new rhetoric of exclusion that legitimized persecution based on new attitudes of stereotyping, stigmatization and even demonization of the accused; by the creation of new civil laws which included allowing the state to be the defendant and bring charges on its own behalf; the invention of police forces as the arm of state enforcement; the invention of a general taxation, gold coins, and modern banking to pay for it all; and the inquisitions, which were a new legal procedure that allowed the judge to investigate on his own initiative without requiring a victim (other than the state) to press charges.[103]: 4, 90–100, 146, 149, 154 [108]: 97–111

"The exceptional character of persecution in the Latin west since the twelfth century has lain not in the scale or savagery of particular persecutions, ... but in its capacity for sustained long-term growth. The patterns, procedures and rhetoric of persecution, which were established in the twelfth century, have given it the power of infinite and indefinite self-generation and self-renewal."[103]: vi, 155

Eventually, this would lead to the development among the early Protestants of the conviction that concepts of religious toleration and separation of church and state were essential.[109]: 3

Canon law, the value of debate, and natural law from medieval universities

Christianity in the High Middle Ages had a lasting impact on politics and law through the newly established universities. Canon law emerged from theology and developed independently there.[110]: 255 By the 1200s, both civil and canon law had become a major aspect of ecclesiastical culture, dominating Christian thought.[111]: 382 Most bishops and Popes of this period were trained lawyers rather than theologians, and much Christian thought of this time became little more than an extension of law. In the High Middle Ages, the religion that had begun by decrying the power of law (Romans 7:1)[dubious ] developed the most complex religious law the world has ever seen.[111]: 382 Canon law became a fertile field for those who advocated strong papal power,[110]: 260 and Brian Downing says that a church-centered empire almost became a reality in this era.[112]: 35 However, Downing says the rule of law, established in the Middle Ages, is one of the reasons why Europe eventually developed democracy instead.[112]: 4

Medieval universities were not secular institutions, but they, and some religious orders, were founded with a respect for dialogue and debate, believing good understanding came from viewing something from multiple sides. Because of this, they incorporated reasoned disputation into their system of studies.[113]: xxxiii Accordingly, the universities would hold what was called a quadlibettal where a 'master' would raise a question, students would provide arguments, and those arguments would be assessed and argued. Brian Law says, "Literally anyone could attend, masters and scholars from other schools, all kinds of ecclesiastics and prelates and even civil authorities, all the 'intellectuals' of the time, who were always attracted to skirmishes of this kind, and all of whom had the right to ask questions and oppose arguments."[113]: xxv In a kind of 'Town Hall Meeting' atmosphere, questions could be raised orally by anyone (a quolibet) about literally anything (de quolibet).[113]: xxv

Thomas Aquinas was a master at the University of Paris, twice, and held quodlibetals. Aquinas interpreted Aristotle on natural law. Alexander Passerin d'Entreves writes that natural law has been assailed for a century and a half, yet it remains an aspect of legal philosophy since much human rights theory is based on it.[114] Aquinas taught that just leadership must work for the "common good". He defines a law as "an ordinance of reason" and that it can't simply be the will of the legislator and be good law. Aquinas says the primary goal of law is that "good is to be done and pursued and evil avoided."[115]

Natural law and human rights

"The philosophical foundation of the liberal concept of human rights can be found in natural law theories",[116][117] and much thinking on natural law is traced to the thought of the Dominican friar, Thomas Aquinas.[118] Aquinas continues to influence the works of leading political and legal philosophers.[118]

According to Aquinas, every law is ultimately derived from what he calls the 'eternal law': God's ordering of all created things. For Aquinas, a human action is good or bad depending on whether it conforms to reason, and it is this participation in the 'eternal law' by the 'rational creature' that is called 'natural law'. Aquinas said natural law is a fundamental principle that is woven into the fabric of human nature. Secularists, such as Hugo Grotius, later expanded the idea of human rights and built on it.

"...one cannot and need not deny that Human Rights are of Western Origin. It cannot be denied, because they are morally based on the Judeo-Christian tradition and Graeco-Roman philosophy; they were codified in the West over many centuries, they have secured an established position in the national declarations of western democracies, and they have been enshrined in the constitutions of those democracies."[119]

Howard Tumber says, "human rights is not a universal doctrine, but is the descendent of one particular religion (Christianity)." This does not suggest Christianity has been superior in its practice or has not had "its share of human rights abuses".[120]

David Gushee says Christianity has a "tragically mixed legacy" when it comes to the application of its own ethics. He examines three cases of "Christendom divided against itself": the crusades and St. Francis' attempt at peacemaking with Muslims; Spanish conquerors and the killing of indigenous peoples and the protests against it; and the on-again off-again persecution and protection of Jews.[121]

Charles Malik, a Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher and theologian was responsible for the drafting and adoption of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Revival of Roman law in the Medieval Inquisition

According to Jennifer Deane, the label Inquisition implies "an institutional coherence and an official unity that never existed in the Middle Ages."[122]: 6 The Medieval Inquisitions were actually a series of separate inquisitions beginning from around 1184 lasting to the 1230s that were in response to dissidents accused of heresy,[123] while the Papal Inquisition (1230s–1302) was created to restore order disrupted by mob violence against heretics. Heresy was a religious, political, and social issue.[124]: 108, 109 As such, "the first stirrings of violence against dissidents were usually the result of popular resentment."[125]: 189 This led to a breakdown of social order.[124]: 108, 109 In the Late Roman Empire, an inquisitorial system of justice had developed, and that is the system that was revived in the Middle Ages. It used a combined panel of both civil and ecclesiastical representatives with a Bishop, his representative, or a local judge, as inquisitor. Essentially, the church reintroduced Roman law in Europe (in the form of the Inquisition) when it seemed that Germanic law had failed.[126] "The Inquisition was not an organization arbitrarily devised and imposed upon the judicial system by the ambition or fanaticism of the church. It was rather a natural—one may almost say an inevitable—evolution of the forces at work in the thirteenth century."[127]

The invention of Holy War, chivalry, and the roots of modern tolerance

In 1095, Pope Urban II called for a Crusade to re-take the Holy Land from Muslim rule. Hugh S. Pyper says "the city importance is reflected in the fact that early medieval maps place at the center of the world."[111]: 338

"By the eleventh century, the Seljuk Turks had conquered . The holdings of the old Eastern Roman Empire, known to modern historians as the Byzantine Empire, were reduced to little more than Greece. In desperation, the emperor in Constantinople sent word to the Christians of western Europe asking them to aid their brothers and sisters in the East."[128][129]

This was the impetus of the first crusade, however, the "Colossus of the Medieval world was Islam, not Christendom" and despite initial success, these conflicts, which lasted four centuries, ultimately ended in failure for western Christendom.[129]

At the time of the First crusade, there was no clear concept of what a crusade was beyond that of a pilgrimage.[130]: 32 Riley-Smith says the crusades were products of the renewed spirituality of the central Middle Ages as much as they were of political circumstances.[131]: 177 Senior churchmen of this time presented the concept of Christian love to the faithful as the reason to take up arms.[131]: 177 The people had a concern for living the vita apostolica and expressing Christian ideals in active works of charity, exemplified by the new hospitals, the pastoral work of the Augustinians and Premonstratensians, and the service of the friars. Riley-Smith concludes, "The charity of St. Francis may now appeal to us more than that of the crusaders, but both sprang from the same roots."[131]: 180, 190–2 Constable adds that those "scholars who see the crusades as the beginning of European colonialism and expansionism would have surprised people at the time. would not have denied some selfish aspects... but the predominant emphasis was on the defense and recovery of lands that had once been Christian and on the self-sacrifice, rather than the self-seeking, of the participants."[130]: 15 Riley-Smith also says scholars are turning away from the idea the crusades were materially motivated.[132]

Ideas such as holy war and Christian chivalry, in both thought and culture, continued to evolve gradually from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries.[104]: 184, 185, 210 This can be traced in expressions of law, traditions, tales, prophecy, and historical narratives, in letters, bulls and poems written during the crusading period.[133]: 715–737

According to political science professor Andrew R. Murphy, concepts of tolerance and intolerance were not starting points for thoughts about relations for any of the various groups involved in or affected by the crusades.[134]: xii–xvii Instead, concepts of tolerance began to grow during the crusades from efforts to define legal limits and the nature of co-existence.[134]: xii Eventually, this would help provide the foundation to the conviction among the early Protestants that pioneering the concept of religious toleration was necessary.[109]: 3

Moral decline and rising political power of the church in the Late Middle Agesedit

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Role_of_Christianity_in_civilizationText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk