A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

Western civilization traces its roots back to Europe and the Mediterranean. It is linked to ancient Greece, the Roman Empire and Medieval Western Christendom which emerged during the Middle Ages and experienced such transformative episodes as the development of Scholasticism, the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, the Scientific Revolution, and the development of liberal democracy. The civilizations of Classical Greece and Ancient Rome are considered seminal periods in Western history. Major cultural contributions also came from the Christianized Germanic peoples, such as the Franks, the Goths, and the Burgundians. Charlemagne founded the Carolingian Empire and he is referred to as the "Father of Europe."[1] Contributions also emerged from pagan peoples of pre-Christian Europe, such as the Celts and Germanic pagans as well as some significant religious contributions derived from Judaism and Hellenistic Judaism stemming back to Second Temple Judea, Galilee, and the early Jewish diaspora;[2][3][4] and some other Middle Eastern influences.[5] Western Christianity has played a prominent role in the shaping of Western civilization, which throughout most of its history, has been nearly equivalent to Christian culture. (There were Christians outside of the West, such as China, India, Russia, Byzantium and the Middle East).[6][7][8][9][10] Western civilization has spread to produce the dominant cultures of modern Americas and Oceania, and has had immense global influence in recent centuries in many ways.

Following the 5th century Fall of Rome, Europe entered the Middle Ages, during which period the Catholic Church filled the power vacuum left in the West by the fall of the Western Roman Empire, while the Eastern Roman Empire (or Byzantine Empire) endured in the East for centuries, becoming a Hellenic Eastern contrast to the Latin West. By the 12th century, Western Europe was experiencing a flowering of art and learning, propelled by the construction of cathedrals, the establishment of medieval universities, and greater contact with the medieval Islamic world via Al-Andalus and Sicily, from where Arabic texts on science and philosophy were translated into Latin. Christian unity was shattered by the Reformation from the 16th century. A merchant class grew out of city states, initially in the Italian peninsula (see Italian city-states), and Europe experienced the Renaissance from the 14th to the 17th century, heralding an age of technological and artistic advance and ushering in the Age of Discovery which saw the rise of such global European empires as those of Portugal and Spain.

The Industrial Revolution began in Britain in the 18th century. Under the influence of the Enlightenment, the Age of Revolution emerged from the United States and France as part of the transformation of the West into its industrialised, democratised modern form. The lands of North and South America, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand became first part of European empires and then home to new Western nations, while Africa and Asia were largely carved up between Western powers. Laboratories of Western democracy were founded in Britain's colonies in Australasia from the mid-19th centuries, while South America largely created new autocracies. In the 20th century, absolute monarchy disappeared from Europe, and despite episodes of Fascism and Communism, by the close of the century, virtually all of Europe was electing its leaders democratically. Most Western nations were heavily involved in the First and Second World Wars and protracted Cold War. World War II saw Fascism defeated in Europe, and the emergence of the United States and Soviet Union as rival global powers and a new "East-West" political contrast.

Other than in Russia, the European empires disintegrated after World War II and civil rights movements and widescale multi-ethnic, multi-faith migrations to Europe, the Americas and Oceania lowered the earlier predominance of ethnic Europeans in Western culture. European nations moved towards greater economic and political co-operation through the European Union. The Cold War ended around 1990 with the collapse of Soviet-imposed Communism in Central and Eastern Europe. In the 21st century, the Western World retains significant global economic power and influence. The West has contributed a great many technological, political, philosophical, artistic and religious aspects to modern international culture: having been a crucible of Catholicism, Protestantism, democracy, industrialisation; the first major civilisation to seek to abolish slavery during the 19th century, the first to enfranchise women (beginning in Australasia at the end of the 19th century) and the first to put to use such technologies as steam, electric and nuclear power. The West invented cinema, television, radio, telephone, the automobile, rocketry, flight, electric light, the personal computer and the Internet; produced artists such as Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Leonardo da Vinci, Beethoven, Vincent van Gogh, Picasso, Bach and Mozart; developed sports such as soccer, cricket, golf, tennis, rugby and basketball; and transported humans to an astronomical object for the first time with the 1969 Apollo 11 Moon Landing.

Antiquity: before AD 500

The Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages: 500–1000

While the Roman Empire and Christian religion survived in an increasingly Hellenised form in the Byzantine Empire centered at Constantinople in the East, Western civilization suffered a collapse of literacy and organization following the fall of Rome in AD 476. Gradually however, the Christian religion re-asserted its influence over Western Europe.

After the Fall of Rome, the papacy served as a source of authority and continuity. In the absence of a magister militum living in Rome, even the control of military matters fell to the pope. Gregory the Great (c 540–604) administered the church with strict reform. A trained Roman lawyer and administrator, and a monk, he represents the shift from the classical to the medieval outlook and was a father of many of the structures of the later Roman Catholic Church. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, he looked upon Church and State as co-operating to form a united whole, which acted in two distinct spheres, ecclesiastical and secular, but by the time of his death, the papacy was the great power in Italy:[11]

Pope Gregory the Great made himself in Italy a power stronger than emperor or exarch, and established a political influence which dominated the peninsula for centuries. From this time forth the varied populations of Italy looked to the pope for guidance, and Rome as the papal capital continued to be the center of the Christian world.

According to tradition, it was a Romanized Briton, Saint Patrick who introduced Christianity to Ireland around the 5th century. Roman legions had never conquered Ireland, and as the Western Roman Empire collapsed, Christianity managed to survive there. Monks sought out refuge at the far fringes of the known world: like Cornwall, Ireland, or the Hebrides. Disciplined scholarship carried on in isolated outposts like Skellig Michael in Ireland, where literate monks became some of the last preservers in Western Europe of the poetic and philosophical works of Western antiquity.[12]

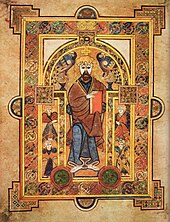

By around 800 they were producing illuminated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells. The missions of Gaelic monasteries led by monks like St Columba spread Christianity back into Western Europe during the Middle Ages, establishing monasteries initially in northern Britain, then through Anglo-Saxon England and the Frankish Empire during the Middle Ages. Thomas Cahill, in his 1995 book How the Irish Saved Civilization, credited Irish Monks with having "saved" Western Civilization during this period.[13] According to art historian Kenneth Clark, for some five centuries after the fall of Rome, virtually all men of intellect joined the Church and practically nobody in western Europe outside of monastic settlements had the ability to read or write.[12]

Around AD 500, Clovis I, the King of the Franks, became a Christian and united Gaul under his rule. Later in the 6th century, the Byzantine Empire restored its rule in much of Italy and Spain. Missionaries sent from Ireland by the Pope helped to convert England to Christianity in the 6th century as well, restoring that faith as the dominant in Western Europe.

Muhammed, the founder and Prophet of Islam was born in Mecca in AD 570. Working as a trader he encountered the ideas of Christianity and Judaism on the fringes of the Byzantine Empire, and around 610 began preaching of a new monotheistic religion, Islam, and in 622 became the civil and spiritual leader of Medina, soon after conquering Mecca in 630. Dying in 632, Muhammed's new creed conquered first the Arabian tribes, then the great Byzantine cities of Damascus in 635 and Jerusalem in 636. A multiethnic Islamic empire was established across the formerly Roman Middle East and North Africa. By the early 8th century, Iberia and Sicily had fallen to the Muslims. By the 9th century, Malta, Cyprus, and Crete had fallen – and for a time the region of Septimania.[14]

Only in 732 was the Muslim advance into Europe stopped by the Frankish leader Charles Martel, saving Gaul and the rest of the West from conquest by Islam. From this time, the "West" became synonymous with Christendom, the territory ruled by Christian powers, as Oriental Christianity fell to dhimmi status under the Muslim Caliphates. The cause to liberate the "Holy Land" remained a major focus throughout medieval history, fueling many consecutive crusades, only the first of which was successful (although it resulted in many atrocities, in Europe as well as elsewhere).

Charlemagne ("Charles the Great" in English) became king of the Franks. He conquered Gaul (modern day France), northern Spain, Saxony, and northern and central Italy. In 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor. Under his rule, his subjects in non-Christian lands like Germany converted to Christianity.

After his reign, the empire he created broke apart into the kingdom of France (from Francia meaning "land of the Franks"), Holy Roman Empire and the kingdom in between (containing modern day Switzerland, northern-Italy, Eastern France and the low-countries).

Starting in the late 8th century, the Vikings began seaborne attacks on the towns and villages of Europe. Eventually, they turned from raiding to conquest, and conquered Ireland, most of England, and northern France (Normandy). These conquests were not long-lasting, however. In 954 Alfred the Great drove the Vikings out of England, which he united under his rule, and Viking rule in Ireland ended as well. In Normandy the Vikings adopted French culture and language, became Christians and were absorbed into the native population.

By the beginning of the 11th century Scandinavia was divided into three kingdoms, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, all of which were Christian and part of Western civilization. Norse explorers reached Iceland, Greenland, and even North America, however only Iceland was permanently settled by the Norse. A period of warm temperatures from around 1000–1200 enabled the establishment of a Norse outpost in Greenland in 985, which survived for some 400 years as the most westerly outpost of Christendom. From here, Norseman attempted their short-lived European colony in North America, five centuries before Columbus.[14]

In the 10th century another marauding group of warriors swept through Europe, the Magyars. They eventually settled in what is today Hungary, converted to Christianity and became the ancestors of the Hungarian people.

A West Slavic people, the Poles, formed a unified state by the 10th century and having adopted Christianity also in the 10th century[15][16] but with pagan rising in the 11th century.

By the start of the second millennium AD, the West had become divided linguistically into three major groups. The Romance languages, based on Latin, the language of the Romans, the Germanic languages, and the Celtic languages. The most widely spoken Romance languages were French, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish. Four widely spoken Germanic languages were English, German, Dutch, and Danish. Irish and Scots Gaelic were two widely spoken Celtic languages in the British Isles.

High Middle Ages: 1000–1300

Art historian Kenneth Clark wrote that Western Europe's first "great age of civilisation" was ready to begin around the year 1000. From 1100, he wrote: "every branch of life – action, philosophy, organisation, technology extraordinary outpouring of energy, an intensification of existence". Upon this period rests the foundations of many of Europe's subsequent achievements. By Clark's account, the Catholic Church was very powerful, essentially internationalist and democratic in its structures and run by monastic organisations generally following the Rule of Saint Benedict. Men of intelligence usually joined religious orders and those of intellectual, administrative or diplomatic skill could advance beyond the usual restraints of society – leading churchmen from faraway lands were accepted in local bishoprics, linking European thought across wide distances. Complexes like the Abbey of Cluny became vibrant centres with dependencies spread throughout Europe. Ordinary people also trekked vast distances on pilgrimages to express their piety and pray at the site of holy relics.

Monumental abbeys and cathedrals were constructed and decorated with sculptures, hangings, mosaics and works belonging to one of the greatest epochs of art and providing stark contrast to the monotonous and cramped conditions of ordinary living. Abbot Suger of the Abbey of St. Denis is considered an influential early patron of Gothic architecture and believed that love of beauty brought people closer to God: "The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material". Clark calls this "the intellectual background of all the sublime works of art of the next century and in fact has remained the basis of our belief of the value of art until today".[12]

By the year 1000 feudalism had become the dominant social, economic and political system. At the top of society was the monarch, who gave land to nobles in exchange for loyalty. The nobles gave land to vassals, who served as knights to defend their monarch or noble. Under the vassals were the peasants or serfs. The feudal system thrived as long as peasants needed protection by the nobility from invasions originating inside and outside of Europe. So as the 11th century progressed, the feudal system declined along with the threat of invasion.[citation needed]

In 1054, after centuries of strained relations, the Great Schism occurred over differences in doctrine, splitting the Christian world between the Catholic Church, centered in Rome and dominant in the West, and the Orthodox Church, centered in Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire. The last pagan land in Europe was converted to Christianity with the conversion of the Baltic peoples in the High Middle Ages, bringing them into Western civilization as well.[17]

As the Medieval period progressed, the aristocratic military ideal of Chivalry and institution of knighthood based around courtesy and service to others became culturally important. Large Gothic cathedrals of extraordinary artistic and architectural intricacy were constructed throughout Europe, including Canterbury Cathedral in England, Cologne Cathedral in Germany and Chartres Cathedral in France (called the "epitome of the first great awakening in European civilisation" by Kenneth Clark[12]). The period produced ever more extravagant art and architecture, but also the virtuous simplicity of such as St Francis of Assisi (expressed in the Prayer of St Francis) and the epic poetry of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. As the Church grew more powerful and wealthy, many sought reform. The Dominican and Franciscan Orders were founded, which emphasized poverty and spirituality.[18]

Women were in many respects excluded from political and mercantile life, however, leading churchwomen were an exception. Medieval abbesses and female superiors of monastic houses were powerful figures whose influence could rival that of male bishops and abbots: "They treated with kings, bishops, and the greatest lords on terms of perfect equality;. . . they were present at all great religious and national solemnities, at the dedication of churches, and even, like the queens, took part in the deliberation of the national assemblies...".[19] The increasing popularity of devotion to the Virgin Mary (the mother of Jesus) secured maternal virtue as a central cultural theme of Catholic Europe. Kenneth Clark wrote that the 'Cult of the Virgin' in the early 12th century "had taught a race of tough and ruthless barbarians the virtues of tenderness and compassion".[12]

In 1095, Pope Urban II called for a Crusade to re-conquer the Holy Land from Muslim rule,[20] when the Seljuk Turks prevented Christians from visiting the holy sites there. For centuries prior to the emergence of Islam, Asia Minor and much of the Mid East had been a part of the Roman and later Byzantine Empires. The Crusades were originally launched in response to a call from the Byzantine Emperor for help to fight the expansion of the Turks into Anatolia.

The First Crusade succeeded in its task, but at a serious cost on the home front, and the crusaders established rule over the Holy Land. However, Muslim forces reconquered the land by the 13th century, and subsequent crusades were not very successful. The specific crusades to restore Christian control of the Holy Land were fought over a period of nearly 200 years, between 1095 and 1291. Other campaigns in Spain and Portugal (the Reconquista), and Northern Crusades continued into the 15th century.

The Crusades had major far-reaching political, economic, and social impacts on Europe. They further served to alienate Eastern and Western Christendom from each other and ultimately failed to prevent the march of the Turks into Europe through the Balkans and the Caucasus.[21]

After the fall of the Roman Empire, many of the classical Greek texts were translated into Arabic and preserved in the medieval Islamic world, from where the Greek classics along with Arabic science and philosophy were transmitted to Western Europe and translated into Latin during the Renaissance of the 12th century and 13th century.[22][23][24]

Cathedral schools began in the Early Middle Ages as centers of advanced education, some of them ultimately evolving into medieval universities. During the High Middle Ages, Chartres Cathedral operated the famous and influential Chartres Cathedral School. The medieval universities of Western Christendom were well-integrated across all of Western Europe, encouraged freedom of enquiry and produced a great variety of fine scholars and natural philosophers, including Robert Grosseteste of the University of Oxford, an early expositor of a systematic method of scientific experimentation;[25] and Saint Albert the Great, a pioneer of biological field research.[26] The Italian University of Bologna is considered the oldest continually operating university.[27][28]

Philosophy in the High Middle Ages focused on religious topics. Christian Platonism, which modified Plato's idea of the separation between the ideal world of the forms and the imperfect world of their physical manifestations to the Christian division between the imperfect body and the higher soul was at first the dominant school of thought. However, in the 12th century the works of Aristotle were reintroduced to the West, which resulted in a new school of inquiry known as scholasticism, which emphasized scientific observation. Two important philosophers of this period were Saint Anselm and Saint Thomas Aquinas, both of whom were concerned with proving God's existence through philosophical means. The Summa Theologica by Aquinas was one of the most influential documents in medieval philosophy and Thomism continues to be studied today in philosophy classes. Theologian Peter Abelard wrote in 1122 "I must understand in order that I may believe... by doubting we come to questioning, and by questioning we perceive the truth".[12]

In Normandy, the Vikings adopted French culture and language, mixed with the native population of mostly Frankish and Gallo-Roman stock and became known as the Normans. They played a major political, military, and cultural role in medieval Europe and even the Near East. They were famed for their martial spirit and Christian piety. They quickly adopted the Romance language of the land they settled in, their dialect becoming known as Norman, an important literary language. The Duchy of Normandy, which they formed by treaty with the French crown, was one of the great large fiefs of medieval France. The Normans are famed both for their culture, such as their unique Romanesque architecture, and their musical traditions, as well as for their military accomplishments and innovations. Norman adventurers established a kingdom in Sicily and southern Italy by conquest, and a Norman expedition on behalf of their duke led to the Norman Conquest of England. Norman influence spread from these new centres to the Crusader States in the Near East, to Scotland and Wales in Great Britain, and to Ireland.[29]

Relations between the major powers in Western society: the nobility, monarchy and clergy, sometimes produced conflict. If a monarch attempted to challenge church power, condemnation from the church could mean a total loss of support among the nobles, peasants, and other monarchs. The Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, one of the most powerful men of the 11th century, stood three days bare-headed in the snow at Canossa in 1077, in order to reverse his excommunication by Pope Gregory VII.[30] As monarchies centralized their power as the Middle Ages progressed, nobles tried to maintain their own authority. The sophisticated Court of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II was based in Sicily, where Norman, Byzantine, and Islamic civilization had intermingled. His realm stretched through Southern Italy, through Germany and in 1229, he crowned himself King of Jerusalem. His reign saw tension and rivalry with the Papacy over control of Northern Italy.[31] A patron of education,[32] Frederick founded the University of Naples.[33]

Plantagenet kings first ruled the Kingdom of England in the 12th century. Henry V left his mark with a famous victory against larger numbers at the Battle of Agincourt, while Richard the Lionheart, who had earlier distinguished himself in the Third Crusade, was later romanticised as an iconic figure in English folklore. A distinctive English culture emerged under the Plantagenets, encouraged by some of the monarchs who were patrons of the "father of English poetry", Geoffrey Chaucer. The Gothic architecture style was popular during the time, with buildings such as Westminster Abbey remodelled in that style. King John's sealing of the Magna Carta was influential in the development of common law and constitutional law. The 1215 Charter required the King to proclaim certain liberties, and accept that his will was not arbitrary — for example by explicitly accepting that no "freeman" (non-serf) could be punished except through the law of the land, a right which is still in existence today. Political institutions such as the Parliament of England and the Model Parliament originate from the Plantagenet period, as do educational institutions including the universities of Cambridge and Oxford.[34][35]

From the 12th century onward inventiveness had re-asserted itself outside of the Viking north and the Islamic south of Europe. Universities flourished, mining of coal commenced, and crucial technological advances such as the lock, which enabled sail ships to reach the thriving Belgian city of Bruges via canals, and the deep sea ship guided by magnetic compass and rudder were invented.[14]

Late Middle Ages: 1300–1500

A cooling in temperatures after about 1150 saw leaner harvests across Europe and consequent shortages of food and flax material for clothing. Famines increased and in 1316 serious famine gripped Ypres. In 1410, the last of the Greenland Norseman abandoned their colony to the ice. From Central Asia, Mongol invasions progressed towards Europe throughout the 13th century, resulting in the vast Mongol Empire which became the largest empire of history and ruled over almost half of the human population and expanded through the world by 1300.[14]

The Papacy had its court at Avignon from 1305 to 1378[36] This arose from the conflict between the Papacy and the French crown. A total of seven popes reigned at Avignon; all were French, and all were increasingly under the influence of the French crown. Finally in 1377 Gregory XI, in part because of the entreaties of the mystic Saint Catherine of Sienna, restored the Holy See to Rome, officially ending the Avignon papacy.[37] However, in 1378 the breakdown in relations between the cardinals and Gregory's successor, Urban VI, gave rise to the Western Schism — which saw another line of Avignon Popes set up as rivals to Rome (subsequent Catholic history does not grant them legitimacy).[38] The period helped weaken the prestige of the Papacy in the buildup to the Protestant Reformation.

In the Later Middle Ages, the Black Plague struck Europe, arriving in 1347.[39] Europe was overwhelmed by the outbreak of bubonic plague, probably brought to Europe by the Mongols. The fleas hosted by rats carried the disease and it devastated Europe. Major cities like Paris, Hamburg, Venice and Florence lost half their population. Around 20 million people – up to a third of Europe's population – died from the plague before it receded. The plague periodically returned over the coming centuries.[14]

The last centuries of the Middle Ages saw the waging of the Hundred Years' War between England and France. The war began in 1337 when the king of France laid claim to English-ruled Gascony in southern France, and the king of England claimed to be the rightful king of France. At first, the English conquered half of France and seemed likely to win the war, until the French were rallied by a peasant girl, who would later become a saint, Joan of Arc. Although she was captured and executed by the English, the French fought on and won the war in 1453. After the war, France gained all of Normandy, excluding the city of Calais, which it gained in 1558.[40]

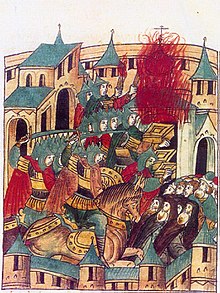

Following the Mongols from Central Asia came the Ottoman Turks. By 1400 they had captured most of modern-day Turkey and extended their rule into Europe through the Balkans and as far as the Danube, surrounding even the fabled city of Constantinople. Finally, in 1453, one of Europe's greatest cities fell to the Turks.[14] The Ottomans under the command of Sultan Mehmed II, fought a vastly outnumbered defending army commanded by Emperor Constantine XI — the last "Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire" — and blasted down the ancient walls with the terrifying new weaponry of the cannon. The Ottoman conquests sent refugee Greek scholars westward, contributing to the revival of the West's knowledge of the learning of Classical Antiquity.

Probably the first clock in Europe was installed in a Milan church in 1335, hinting at the dawning mechanical age.[14] By the 14th century, the middle class in Europe had grown in influence and number as the feudal system declined. This spurred the growth of towns and cities in the West and improved the economy of Europe. This, in turn helped begin a cultural movement in the West known as the Renaissance, which began in Italy. Italy was dominated by city-states, many of which were nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire, and were ruled by wealthy aristocrats like the Medicis, or in some cases, by the pope.

Renaissance and Reformation

The Renaissance: 14th to 17th century

The Renaissance, originating from Italy, ushered in a new age of scientific and intellectual inquiry and appreciation of ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. The merchant cities of Florence, Genoa, Ghent, Nuremberg, Geneva, Zürich, Lisbon and Seville provided patrons of the arts and sciences and unleashed a flurry of activity.

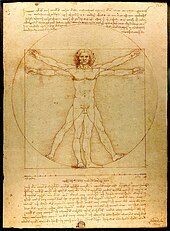

The Medici became the leading family of Florence and fostered and inspired the birth of the Italian Renaissance along with other families of Italy, such as the Visconti and Sforza of Milan, the Este of Ferrara, and the Gonzaga of Mantua. Greatest artists like Brunelleschi, Botticelli, Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Giotto, Donatello, Titian and Raphael produced inspired works – their paintwork was more realistic-looking than had been created by Medieval artists and their marble statues rivalled and sometimes surpassed those of Classical Antiquity. Michelangelo carved his masterpiece David from marble between 1501 and 1504.

Humanist historian Leonardo Bruni, split the history in the antiquity, Middle Ages and modern period.

Churches began being built in the Romanesque style for the first time in centuries. While art and architecture flourished in Italy and then the Netherlands, religious reformers flowered in Germany and Switzerland; printing was establishing itself in the Rhineland and navigators were embarking on extraordinary voyages of discovery from Portugal and Spain.[14]

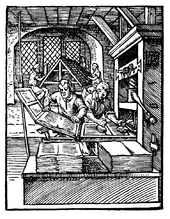

Around 1450, Johannes Gutenberg developed a printing press, which allowed works of literature to spread more quickly.[41] Secular thinkers like Machiavelli re-examined the history of Rome to draw lessons for civic governance. Theologians revisited the works of St Augustine. Important thinkers of the Renaissance in Northern Europe included the Catholic humanists Desiderius Erasmus, a Dutch theologian, and the English statesman and philosopher Thomas More, who wrote the seminal work Utopia in 1516. Humanism was an important development to emerge from the Renaissance. It placed importance on the study of human nature and worldly topics rather than religious ones. Important humanists of the time included the writers Petrarch and Boccaccio, who wrote in both Latin as had been done in the Middle Ages, as well as the vernacular, in their case Tuscan Italian.

As the calendar reached the year 1500, Europe was blossoming – with Leonardo da Vinci painting his Mona Lisa portrait not long after Christopher Columbus reached the Americas (1492), Amerigo Vespucci proofed that America is not a part of India, the Portuguese navigator Vasco Da Gama sailed around Africa into the Indian Ocean and Michelangelo completed his paintings of Old Testament themes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome (the expense of such artistic exuberance did much to spur the likes of Martin Luther in Northern Europe in their protests against the Church of Rome).[14]

For the first time in European history, events North of the Alps and on the Atlantic Coast were taking centre stage.[14] Important artists of this period included Bosch, Dürer, and Breugel. In Spain Miguel de Cervantes wrote the novel Don Quixote, other important works of literature in this period were the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer and Le Morte d'Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory. The most famous playwright of the era was the Englishman William Shakespeare whose sonnets and plays (including Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet and Macbeth) are considered some of the finest works ever written in the English language.

Meanwhile, the Christian kingdoms of northern Iberia continued their centuries-long fight to reconquer the peninsula from its Muslim rulers. In 1492, the last Islamic stronghold, Granada, fell, and Iberia was divided between the Christian kingdoms of Spain and Portugal. Iberia's Jewish and Muslim minorities were forced to convert to Catholicism or be exiled. The Portuguese immediately looked to expand outward sending expeditions to explore the coasts of Africa and engage in trade with the mostly Muslim powers on the Indian Ocean, making Portugal wealthy. In 1492, a Spanish expedition of Christopher Columbus found the Americas during an attempt to find a western route to East Asia.

From the East, however, the Ottoman Turks under Suleiman the Magnificent continued their advance into the heart of Christian Europe — besieging Vienna in 1529.[14]

The 16th century saw the flowering of the Renaissance in the rest of the West. In the Kingdom of Poland, astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus deduced that the geocentric model of the universe was incorrect, and that in fact the planets revolve around the sun. In the Netherlands, the invention of the telescope and the microscope resulted in the investigation of the universe and the microscopic world. The father of modern science Galileo and Christiaan Huygens developed more advance telescopes and used these in their scientific research. The father of microbiology, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek pioneered the use of the microscope in the study of microbes and established microbiology as a scientific discipline. Advances in medicine and understanding of the human anatomy also increased in this time. Gerolamo Cardano partially invented several machines and introduced essential mathematics theories. In England, Sir Isaac Newton pioneered the science of physics. These events led to the so-called scientific revolution, which emphasized experimentation.

The Reformation: 1500–1650

The other major movement in the West in the 16th century was the Reformation, which would profoundly change the West and end its religious unity. The Reformation began in 1517 when the Catholic monk Martin Luther wrote his 95 Theses, which denounced the wealth and corruption of the church, as well as many Catholic beliefs, including the institution of the papacy and the belief that, in addition to faith in Christ, "good works" were also necessary for salvation. Luther drew on the beliefs of earlier church critics, like the Bohemian Jan Hus and the Englishman John Wycliffe. Luther's beliefs eventually ended in his excommunication from the Catholic Church and the founding of a church based on his teachings: the Lutheran Church, which became the majority religion in northern Germany. Soon other reformers emerged, and their followers became known as Protestants. In 1525, Ducal Prussia became the first Lutheran state.[42]

In the 1540s the Frenchman John Calvin founded a church in Geneva which forbade alcohol and dancing, and which taught God had selected those destined to be saved from the beginning of time. His Calvinist Church gained about half of Switzerland and churches based on his teachings became dominant in the Netherlands (the Dutch Reformed Church) and Scotland (the Presbyterian Church). In England, when the Pope failed to grant King Henry VIII a divorce, he declared himself head of the Church in England (founding what would evolve into today's Church of England and Anglican Communion). Some Englishmen felt the church was still too similar to the Catholic Church and formed the more radical Puritanism. Many other small Protestant sects were formed, including Zwinglianism, Anabaptism and Mennonism. Although they were different in many ways, Protestants generally called their religious leaders ministers instead of priests, and believed only the Bible, and not Tradition offered divine revelation.

Britain and the Dutch Republic allowed Protestant dissenters to migrate to their North American colonies – thus the future United States found its early Protestant ethos – while Protestants were forbidden to migrate to the Spanish colonies (thus South America retained its Catholic hue). A more democratic organisational structure within some of the new Protestant movements – as in the Calvinists of New England – did much also to foster a democratic spirit in Britain's American colonies.[14]

The Catholic Church responded to the Reformation with the Counter Reformation. Some of Luther and Calvin's criticisms were heeded: the selling of indulgences was reined in by the Council of Trent in 1562. But exuberant baroque architecture and art was embraced as an affirmation of the faith and new seminaries and orders were established to lead missions to far off lands.[14] An important leader in this movement was Saint Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Society of Jesus (Jesuit Order) which gained many converts and sent such famous missionaries as Saints Matteo Ricci to China, Francis Xavier to India and Peter Claver to the Americas.

As princes, kings and emperors chose sides in religious debates and sought national unity, religious wars erupted throughout Europe, especially in the Holy Roman Empire. Emperor Charles V was able to arrange the Peace of Augsburg between the warring Catholic and Protestant nobility. However, in 1618, the Thirty Years' War began between Protestants and Catholics in the empire, which eventually involved neighboring countries like France. The devastating war finally ended in 1648. In the Peace of Westphalia ending the war, Lutheranism, Catholicism and Calvinism were all granted toleration in the empire. The two major centers of power in the empire after the war were Protestant Prussia in the north and Catholic Austria in the south. The Dutch, who were ruled by the Spanish at the time, revolted and gained independence, founding a Protestant country. The Elizabethan era is famous above all for the flourishing of English drama, led by playwrights such as William Shakespeare and for the seafaring prowess of English adventurers such as Sir Francis Drake. Her 44 years on the throne provided welcome stability and helped forge a sense of national identity. One of her first moves as queen was to support the establishment of an English Protestant church, of which she became the Supreme Governor of what was to become the Church of England.

By 1650, the religious map of Europe had been redrawn: Scandinavia, Iceland, north Germany, part of Switzerland, Netherlands and Britain were Protestant, while the rest of the West remained Catholic. A byproduct of the Reformation was increasing literacy as Protestant powers pursued an aim of educating more people to be able to read the Bible.[43]

Rise of Western empires: 1500–1800

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

From its dawn until modern times, the West had suffered invasions from Africa, Asia, and non-Western parts of Europe. By 1500 Westerners took advantage of their new technologies, sallied forth into unknown waters, expanded their power and the Age of Discovery began, with Western explorers from seafaring nations like Portugal and Castile (later Spain) and later Holland, France and England setting forth from the "Old World" to chart faraway shipping routes and discover "new worlds".

In 1492, the Genovese born mariner, Christopher Columbus set out under the auspices of the Crown of Castile (Spain) to seek an oversea route to the East Indies via the Atlantic Ocean. Rather than Asia, Columbus landed in the Bahamas, in the Caribbean. Spanish colonization followed and Europe established Western Civilization in the Americas. The Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama led the first sailing expedition directly from Europe to India in 1497–1499, by the Atlantic and Indian oceans, opening up the possibility of trade with the East other than via perilous overland routes like the Silk Road. Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer working for the Spanish Crown (under the Crown of Castile), led an expedition in 1519–1522 which became the first to sail from the Atlantic Ocean into the Pacific Ocean and the first to cross the Pacific. The Spanish explorer Juan Sebastián Elcano completed the first circumnavigation of the Earth (Magellan was killed in the Philippines).

The Americas were deeply affected by European expansion, due to conquest, sickness, and introduction of new technologies and ways of life. The Spanish Conquistadors conquered most of the Caribbean islands and overran the two great New World empires: the Aztec Empire of Mexico and the Inca Empire of Peru. From there, Spain conquered about half of South America, all of Central America and much of North America. Portugal also expanded in the Americas, attempting to establish some fishing colonies in northern North America first (with a relatively limited duration) and conquering half of South America and calling their colony Brazil. These Western powers were aided not only by superior technology like gunpowder, but also by Old World diseases which they inadvertently brought with them, and which wiped out large segments of the Amerindian population. The native populations, called Indians by Columbus, since he originally thought he had landed in Asia (but often called Amerindians by scholars today), were converted to Catholicism and adopted the language of their rulers, either Spanish or Portuguese. They also adopted much of Western culture. Many Iberian settlers arrived, and many of them intermarried with the Amerindians resulting in a so-called Mestizo population, which became the majority of the population of Spain's American empires.

Other European colonial powers followed in their wake, most prominently the English, Dutch, and French. All three nations established colonies through North and South America and the West Indies. English colonies were established on Caribbean islands such as Barbados, Saint Kitts and Antigua and on North America (largely through a proprietary system) in regions such as Maryland, Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Dutch and French colonization efforts followed a similar pattern, focusing on the Caribbean and North America. The islands of Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten gradually came under Dutch control, while the Dutch established the colony of New Netherland in North America. France gradually colonized Louisiana and Quebec during the 17th and 18th centuries, and transformed its West Indian colony of Saint-Domingue into the wealthiest European overseas possession in the 18th century through a slave-based plantation economy.[44]

In the Americas, it seems that only the most remote peoples managed to stave off complete assimilation by Western and Western-fashioned governments. These include some of the northern peoples (i.e., Inuit), some peoples in the Yucatán, Amazonian forest dwellers, and various Andean groups. Of these, the Quechua people, Aymara people, and Maya people are the most numerous: at around 10–11 million, 2 million, and 7 million, respectively.[45][46][47] Bolivia is the only country in the Americas with an indigenous majority.[48]

Contact between the Old and New Worlds produced the Columbian Exchange, named after Columbus. It involved the transfer of goods unique to one hemisphere to another. Westerners brought cattle, horses, and sheep to the New World, and from the New World Europeans received tobacco, potatoes, and bananas. Other items becoming important in global trade were the sugarcane and cotton crops of the Americas, and the gold and silver brought from the Americas not only to Europe but elsewhere in the Old World.

As European settlers began to colonize the Americas, numerous cash crop plantations sprung up to accommodate increasing demand in Europe. Initially, the labour source of these plantations came from European indentured servants; however, soon this system was supplemented by enslaved Africans imported by European slavers from Africa to the Americas via the transatlantic slave trade. Roughly 12 million enslaved Africans were forcibly transported to the Americas, primarily to the West Indies and South America. Once there, they were primarily forced to work on these plantations in brutal conditions, cultivating crops such as sugar, cotton and tobacco. Together with European trade to Africa and American trade to Europe, this trade was known as the "triangular trade".[49][50] Slavery continued to underpin the economies of European colonies throughout the Americas until the abolitionist movement and slave resistance led to its abolition in the 19th century.[51][52]

After trading with African rulers for some time, Westerners began establishing colonies in Africa. The Portuguese conquered ports in North, West and East Africa and inland territory in what is today Angola and Mozambique. They also established relations with the Kingdom of Kongo in central Africa before, and eventually the Kongolese converted to Catholicism. The Dutch established colonies in modern-day South Africa, which attracted many Dutch settlers. Western powers also established colonies in West Africa. However, most of the continent remained unknown to Westerners and their colonies were restricted to Africa's coasts.

Westerners also expanded in Asia. The Portuguese controlled port cities in the East Indies, India, Persian Gulf, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia and China. During this time, the Dutch began their colonisation of the Indonesian archipelago, which became the Dutch East Indies in the early 19th century, and gained port cities in Sri Lanka and Malaysia and India. Spain conquered the Philippines and converted the inhabitants to Catholicism. Missionaries from Iberia (including some from Italy and France) gained many converts in Japan until Christianity was outlawed by Japan's emperor. Some Chinese also became Christian, although most did not. Most of India was divided up between England and France.

As Western powers expanded they competed for land and resources. In the Caribbean, pirates attacked each other and the navies and colonial cities of countries, in hopes of stealing gold and other valuables from a ship or city. This was sometimes supported by governments. For example, England supported the pirate Sir Francis Drake in raids against the Spanish. Between 1652 and 1678, the three Anglo-Dutch wars were fought, of which the last two were won by the Dutch. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, England gained New Netherland (which was traded with Suriname and Dutch South Africa). In 1756, the Seven Years' War, or French and Indian War began. It involved several powers fighting on several continents. In North America, English soldiers and colonial troops defeated the French, and in India the French were also defeated by England. In Europe Prussia defeated Austria. When the war ended in 1763, New France and eastern Louisiana were ceded to England, while western Louisiana was given to Spain. France's lands in India were ceded to England. Prussia was given rule over more territory in what is today Germany.

The Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon had been the first documented Westerner to land in Australia in 1606[53][54][55] Another Dutchman, Abel Tasman later touched mainland Australia, and mapped Tasmania and New Zealand for the first time, in the 1640s. The English navigator James Cook became first to map the east coast of Australia in 1770. Cook's extraordinary seamanship greatly expanded European awareness of far shores and oceans: his first voyage reported favourably on the prospects of colonisation of Australia; his second voyage ventured almost to Antarctica (disproving long held European hopes of an undiscovered Great Southern Continent); and his third voyage explored the Pacific coasts of North America and Siberia and brought him to Hawaii, where an ill-advised return after a lengthy stay saw him clubbed to death by natives.[56]

Europe's period of expansion in early modern times greatly changed the world. New crops from the Americas improved European diets. This, combined with an improved economy thanks to Europe's new network of colonies, led to a demographic revolution in the West, with infant mortality dropping, and Europeans getting married younger and having more children. The West became more sophisticated economically, adopting Mercantilism, in which companies were state-owned and colonies existed for the good of the mother country.

Enlightenment

Absolutism and the Enlightenment: 1500–1800

The West in the early modern era went through great changes as the traditional balance between monarchy, nobility and clergy shifted. With the feudal system all but gone, nobles lost their traditional source of power. Meanwhile, in Protestant countries, the church was now often headed by a monarch, while in Catholic countries, conflicts between monarchs and the Church rarely occurred and monarchs were able to wield greater power than they ever had in Western history.[citation needed] Under the doctrine of the Divine right of kings, monarchs believed they were only answerable to God: thus giving rise to absolutism.

At the opening of the 15th century, tensions were still going on between Islam and Christianity. Europe, dominated by Christians, remained under threat from the Muslim Ottoman Turks. The Turks had migrated from central to western Asia and converted to Islam years earlier. Their capture of Constantinople in 1453, thus extinguishing the Eastern Roman Empire, was a crowning achievement for the new Ottoman Empire. They continued to expand across the Middle East, North Africa and the Balkans. Under the leadership of the Spanish, a Christian coalition destroyed the Ottoman navy at the battle of Lepanto in 1571 ending their naval control of the Mediterranean. However, the Ottoman threat to Europe was not ended until a Polish led coalition defeated the Ottoman at the Battle of Vienna in 1683.[57][58] The Turks were driven out of Buda (the eastern part of Budapest they had occupied for a century), Belgrade, and Athens – though Athens was to be recaptured and held until 1829.[14]

The 16th century is often called Spain's Siglo de Oro (golden century).[59] From its colonies in the Americas it gained large quantities of gold and silver, which helped make Spain the richest and most powerful country in the world. One of the greatest Spanish monarchs of the era was Charles I (1516–1556, who also held the title of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V). His attempt to unite these lands was thwarted by the divisions caused by the Reformation and ambitions of local rulers and rival rulers from other countries. Another great monarch was Philip II (1556–1598), whose reign was marked by several Reformation conflicts, like the loss of the Netherlands and the Spanish Armada. These events and an excess of spending would lead to a great decline in Spanish power and influence by the 17th century.

After Spain began to decline in the 17th century, the Dutch, by virtue of its sailing ships, became the greatest world power, leading the 17th century to be called the Dutch Golden Age. The Dutch followed Portugal and Spain in establishing an overseas colonial empire — often under the corporate colonialism model of the East India and West India Companies. After the Anglo-Dutch Wars, France and England emerged as the two greatest powers in the 18th century.[60]

Louis XIV became king of France in 1643. His reign was one of the most opulent in European history. He built a large palace in the town of Versailles.

The Holy Roman Emperor exerted no great influence on the lands of the Holy Roman Empire by the end of the Thirty Years' War. In the north of the empire, Prussia emerged as a powerful Protestant nation. Under many gifted rulers, like King Frederick the Great, Prussia expanded its power and defeated its rival Austria many times in war. Ruled by the Habsburg dynasty, Austria became a great empire, expanding at the expense of the Ottoman Empire and Hungary.

One land where absolutism did not take hold was England, which had trouble with revolutionaries. Elizabeth I, daughter of Henry VIII, had left no direct heir to the throne. The rightful heir was actually James VI of Scotland, who was crowned James I of England. James's son, Charles I resisted the power of Parliament. When Charles attempted to shut down Parliament, the Parliamentarians rose up and soon all of England was involved in a civil war. The English Civil War ended in 1649 with the defeat and execution of Charles I. Parliament declared a kingless Commonwealth but soon appointed the anti-absolutist leader and staunch Puritan Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector. Cromwell enacted many unpopular Puritan religious laws in England, like outlawing alcohol and theaters, although religious diversity may have grown. (It was Cromwell, after all, that invited the Jews back into England after the Edict of Expulsion.) After his death, the monarchy was restored under Charles's son, who was crowned Charles II. His son, James II succeeded him. James and his infant son were Catholics.

Not wanting to be ruled by a Catholic dynasty, Parliament invited James's daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange, to rule as co-monarchs. They agreed on the condition James would not be harmed. Realizing he could not count on the Protestant English army to defend him, he abdicated following the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Before William III and Mary II were crowned however, Parliament forced them to sign the English Bill of Rights, which guaranteed some basic rights to all Englishmen, granted religious freedom to non-Anglican Protestants, and firmly established the rights of Parliament. In 1707, the Act of Union of 1707 were passed by the parliaments of Scotland and England, merging Scotland and England into a single Kingdom of Great Britain, with a single parliament. This new kingdom also controlled Ireland which had previously been conquered by England. Following the Irish Rebellion of 1798, in 1801 Ireland was formally merged with Great Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Ruled by the Protestant Ascendancy, Ireland eventually became an English-speaking land, though the majority population preserved distinct cultural and religious outlooks, remaining predomininantly Catholic except in parts of Ulster and Dublin. By then, the British experience had already contributed to the American Revolution.

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was an important European center for the development of modern social and political ideas. It was famous for its rare quasi-democratic political system, praised by philosophers such as Erasmus; and, during the Counter-Reformation, was known for near-unparalleled religious tolerance, with peacefully coexisting Catholic, Jewish, Eastern Orthodox, Protestant and Muslim communities. With its political system the Commonwealth gave birth to political philosophers such as Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski (1503–1572), Wawrzyniec Grzymała Goślicki (1530–1607) and Piotr Skarga (1536–1612). Later, works by Stanisław Staszic (1755–1826) and Hugo Kołłątaj (1750–1812) helped pave the way for the Constitution of 3 May 1791, which historian Norman Davies calls "the first constitution of its kind in Europe".[61] Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth's constitution enacted revolutionary political principles for the first time on the European continent. The Komisja Edukacji Narodowej, Polish for Commission of National Education, formed in 1773, was the world's first national Ministry of Education and an important achievement of the Polish Enlightenment.[62]

The intellectual movement called the Age of Enlightenment began in this period as well. Its proponents opposed the absolute rule of the monarchs, and instead emphasized the equality of all individuals and the idea that governments should derive their existence from the consent of the governed. Enlightenment thinkers called philosophes (French for philosophers) idealized Europe's classical heritage. They looked at Athenian democracy and the Roman Republic as ideal governments. They believed reason held the key to creating an ideal society.[63]

The Englishman Francis Bacon espoused the idea that senses should be the primary means of knowing, while the Frenchman René Descartes advocated using reason over the senses. In his works, Descartes was concerned with using reason to prove his own existence and the existence of the external world, including God. Another belief system became popular among philosophes, Deism, which taught that a single god had created but did not interfere with the world. This belief system never gained popular support and largely died out by the early 19th century.

Thomas Hobbes was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy. His 1651 book Leviathan established the foundation for most of Western political philosophy from the perspective of social contract theory.[64] The theory was examined also by John Locke (Second Treatise of Government (1689)) and Rousseau (Du contrat social (1762)). Social contract arguments examine the appropriate relationship between government and the governed and posit that individuals unite into political societies by a process of mutual consent, agreeing to abide by common rules and accept corresponding duties to protect themselves and one another from violence and other kinds of harm.

In 1690 John Locke wrote that people have certain natural rights like life, liberty and property and that governments were created in order to protect these rights. If they did not, according to Locke, the people had a right to overthrow their government. The French philosopher Voltaire criticized the monarchy and the Church for what he saw as hypocrisy and for their persecution of people of other faiths. Another Frenchman, Montesquieu, advocated division of government into executive, legislative and judicial branches. The French author Rousseau stated in his works that society corrupted individuals. Many monarchs were affected by these ideas, and they became known to history as the enlightened despots. However, most only supported Enlightenment ideas that strengthened their own power.[citation needed]

The Scottish Enlightenment was a period in 18th century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. Scotland reaped the benefits of establishing Europe's first public education system and a growth in trade which followed the Act of Union with England of 1707 and expansion of the British Empire. Important modern attitudes towards the relationship between science and religion were developed by the philosopher/historian David Hume. Adam Smith developed and published The Wealth of Nations, the first work in modern economics. He believed competition and private enterprise could increase the common good. The celebrated bard Robert Burns is still widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland.

European cities like Paris, London, and Vienna grew into large metropolises in early modern times. France became the cultural center of the West. The middle class grew even more influential and wealthy. Great artists of this period included El Greco, Rembrandt, and Caravaggio.

By this time, many around the world wondered how the West had become so advanced, for example, the Orthodox Christian Russians, who came to power after conquering the Mongols that had conquered Kiev in the Middle Ages. They began westernizing under Czar Peter the Great, although Russia remained uniquely part of its own civilization. The Russians became involved in European politics, dividing up the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth with Prussia and Austria.

Revolution: 1770–1815

During the late 18th century and early 19th century, much of the West experienced a series of revolutions that would change the course of history, resulting in new ideologies and changes in society. The first of these revolutions began in North America. The Thirteen Colonies of British North America had by this period. The majority of the population was of English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish descent, while significant minorities included people of French, Dutch and German and Africa descent, as well as some Native Americans. Most of the population was Anglican, others were Congregationalist or Puritan, while minorities included other Protestant churches like the Society of Friends and the Lutherans, as well as some Roman Catholics and Jews. The colonies had their own great cities and universities and continually welcomed new immigrants, mostly from Britain. After the expensive Seven Years' War, Britain needed to raise revenue, and felt the colonists should bare the brunt of the new taxation it felt was necessary. The colonists greatly resented these taxes and protested the fact they could be taxed by Britain but had no representation in the government.

After Britain's King George III refused to seriously consider colonial grievances raised at the first Continental Congress, some colonists took up arms. Leaders of a new pro-independence movement were influenced by Enlightenment ideals and hoped to bring an ideal nation into existence. On 4 July 1776, the colonies declared independence with the signing of the United States Declaration of Independence. Drafted primarily by Thomas Jefferson, the document's preamble eloquently outlines the principles of governance that would come to increasingly dominate Western thinking over the ensuing century and a half:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.

George Washington led the new Continental Army against the British forces, who had many successes early in this American Revolution. After years of fighting, the colonists formed an alliance with France and defeated the British at Yorktown, Virginia in 1781. The treaty ending the war granted independence to the colonies, which became The United States of America.

The other major Western revolution at the turn of the 19th century was the French Revolution. In 1789 France faced an economical crisis. The King called, for the first time in more than two centuries, the Estates General, an assembly of representatives of each estate of the kingdom: the First Estate (the clergy), the Second Estate (the nobility), and the Third Estate (middle class and peasants); in order to deal with the crisis. As the French society was gained by the same Enlightenment ideals that led to the American revolution, in which many Frenchmen, such as Lafayette, took part; representatives of the Third Estate, joined by some representatives of the lower clergy, created the National Assembly, which, unlike the Estates General, provided the common people of France with a voice proportionate to their numbers.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=History_of_Western_civilization

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk