A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

A circular economy (also referred to as circularity or CE)[2] is a model of resource production and consumption in any economy that involves sharing, leasing, reusing, repairing, refurbishing, and recycling existing materials and products for as long as possible.[3][4][5][6] The concept aims to tackle global challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution by emphasizing the design-based implementation of the three base principles of the model. The main three principles required for the transformation to a circular economy are: designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems.[7] CE is defined in contradistinction to the traditional linear economy.[8][9] The idea and concepts of a circular economy have been studied extensively in academia, business, and government over the past ten years. It has been gaining popularity because it can help to minimize carbon emissions and the consumption of raw materials, open up new market prospects, and, principally, increase the sustainability of consumption.[10][11]

At a government level, a circular economy is viewed as a method of combating global warming, as well as a facilitator of long-term growth.[12] CE may geographically connect actors and resources to stop material loops at the regional level.[13] In its core principle, the European Parliament defines CE as "a model of production and consumption that involves sharing, leasing, reusing, repairing, refurbishing, and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible. In this way, the life cycle of products is extended."[4] Global implementation of circular economy can reduce global emissions by 22.8 billion tons, 39% of global emissions in the year 2019.[14] By implementing circular economy strategies in five sectors alone: cement, aluminum, steel, plastics, and food 9.3 billion metric tons of CO2 equivalent (equal to all current emissions from transportation), can be reduced.[15][16][17]

In a circular economy, business models play a crucial role in enabling the shift from linear to circular processes. Various business models have been identified that support circularity, including product-as-a-service, sharing platforms, and product life extension models, among others.[18] These models aim to optimize resource utilization, reduce waste, and create value for businesses and customers alike, while contributing to the overall goals of the circular economy.

Businesses can also make the transition to the circular economy, where holistic adaptations in firms' business models are needed.[19][20] The implementation of circular economy principles often requires new visions and strategies and a fundamental redesign of product concepts, service offerings, and channels towards long-life solutions, resulting in the so-called 'circular business models'.[21] [22]

Definition

There are many definitions of the circular economy.[23] For example, in China, CE is promoted as a top-down national political objective, meanwhile in other areas, such as the European Union, Japan, and the USA, it is a tool to design bottom-up environmental and waste management policies. The ultimate goal of promoting CE is the decoupling of environmental pressure from economic growth.[24] A comprehensive definition could be: "Circular economy is an economic system that targets zero waste and pollution throughout materials lifecycles, from environment extraction to industrial transformation, and final consumers, applying to all involved ecosystems. Upon its lifetime end, materials return to either an industrial process or, in the case of a treated organic residual, safely back to the environment as in a natural regenerating cycle. It operates by creating value at the macro, meso, and micro levels and exploiting to the fullest the sustainability nested concept. Used energy sources are clean and renewable. Resource use and consumption are efficient. Government agencies and responsible consumers play an active role in ensuring the correct system long-term operation."[25]

More generally, circular development is a model of economic, social, and environmental production and consumption that aims to build an autonomous and sustainable society in tune with the issue of environmental resources.[26] The circular economy aims to transform our economy into one that is regenerative. An economy that innovates to reduce waste and the ecological and environmental impact of industries prior to happening, rather than waiting to address the consequences of these issues.[27] This is done by designing new processes and solutions for the optimization of resources, decoupling reliance on finite resources.[26]

The circular economy is a framework of three principles, driven by design: eliminating waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems.[8] It is based increasingly on renewable energy and materials, and it is accelerated by digital innovation. It is a resilient, distributed, diverse, and inclusive economic model. The circular economy is an economic concept often linked to sustainable development, provision of the Sustainable Development Goals (Global Development Goals), and an extension of a green economy.[citation needed]

Other definitions and precise thresholds that separate linear from circular activity have also been developed in the economic literature.[28][23][24]

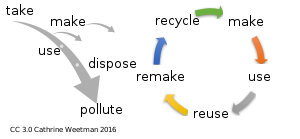

In a linear economy, natural resources are turned into products that are ultimately destined to become waste because of the way they have been designed and manufactured. This process is often summarized as "take, make, waste."[29] By contrast, a circular economy aims to transition from a 'take-make-waste' approach to a more restorative and regenerative system. It employs reuse, sharing, repair, refurbishment, remanufacturing and recycling to create a closed-loop system, reducing the use of resource inputs and the creation of waste, pollution, and carbon emissions.[30] The circular economy aims to keep products, materials, equipment, and infrastructure[31] in use for longer, thus improving the productivity of these resources. Waste materials and energy should become input for other processes through waste valorization: either as a component for another industrial process or as regenerative resources for nature (e.g., compost). The Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) defines the circular economy as an industrial economy that is restorative or regenerative by value and design.[32][33]

Circular economy strategies can be applied at various scales, from individual products and services to entire industries and cities. For example, industrial symbiosis is a strategy where waste from one industry becomes an input for another, creating a network of resource exchange and reducing waste, pollution, and resource consumption.[34] Similarly, circular cities aim to integrate circular principles into urban planning and development, foster local resource loops, and promote sustainable lifestyles among their citizens.[35] Less than 10% of economic activity worldwide in 2022 and 2023 is circular.[16][36] Every year, the global population uses approximately 100 billion tonnes of materials, with more than 90% of them being wasted. The circular economy seeks to address this by eliminating waste entirely.[37]

History and aims

The concept of a circular economy cannot be traced back to one single date or author, rather to different schools of thought.[38]

The concept of a circular economy can be linked to various schools of thought, including industrial ecology, biomimicry, and cradle-to-cradle design principles. Industrial ecology is the study of material and energy flows through industrial systems, which forms the basis of the circular economy. Biomimicry involves emulating nature's time-tested patterns and strategies in designing human systems. Cradle-to-cradle design is a holistic approach to designing products and systems that considers their entire life cycle, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal, and seeks to minimize waste and maximize resource efficiency. These interrelated concepts contribute to the development and implementation of the circular economy.[39]

General systems theory, founded by the biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy, considers growth and energy for open and closed state systems. This theory was then applied to other areas, such as, in the case of the circular economy, economics.[citation needed] Economist Kenneth E. Boulding, in his paper "The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth," argued that a circular economic system is a prerequisite for the maintenance of the sustainability of human life on Earth.[40] Boulding describes the so-called "cowboy economy" as an open system in which the natural environment is typically perceived as limitless: no limit exists on the capacity of the outside to supply or receive energy and material flows.

Walter R. Stahel and Geneviève Reday-Mulvey, in their book "The Potential for Substituting Manpower for Energy," lay the foundation for the principles of the circular economy by describing how increasing labour may reduce energy intensive activities.

Simple economic models have ignored the economy-environment interrelationships. Allan Kneese in "The Economics of Natural Resources" indicates how resources are not endlessly renewable, and mentions the term circular economy for the first time explicitly in 1988.[41]

In their book Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment, Pearce and Turner explain the shift from the traditional linear or open-ended economic system to the circular economic system (Pearce and Turner, 1990).[42] They describe an economic system where waste at extraction, production, and consumption stages is turned into inputs.

In the early 2000s, China integrated the notion into its industrial and environmental policies to make them resource-oriented, production-oriented, waste-oriented, use-oriented, and life cycle-oriented.[43] The Ellen MacArthur Foundation [44] was instrumental in the diffusion of the concept in Europe and the Americas.[45]

In 2010, the concept of circular economy started to become popular internationally after the publication of several reports.[40]

The European Union introduced its vision of the circular economy in 2014, with a New Circular Economy Action Plan launched in 2020 that "shows the way to a climate-neutral, competitive economy of empowered consumers".[45]

The original diffusion of the notion benefited from three major events: the explosion of raw material prices between 2000 and 2010, the Chinese control of rare earth materials, and the 2008 economic crisis.[46] Today, the climate emergency and environmental challenges induce companies and individuals in rethink their production and consumption patterns. The circular economy is framed as one of the answers to these challenges. Key macro-arguments in favour of the circular economy are that it could enable economic growth that does not add to the burden on natural resource extraction but decouples resource uses from the development of economic welfare for a growing population, reduces foreign dependence on critical materials, lowers CO2 emissions, reduces waste production, and introduces new modes of production and consumption able to create further value.[4] Corporate arguments in favour of the circular economy are that it could secure the supply of raw materials, reduce the price volatility of inputs and control costs, reduce spills and waste, extend the life cycle of products, serve new segments of customers, and generate long-term shareholder value. A key idea behind the circular business models is to create loops throughout to recapture value that would otherwise be lost.[47]

Of particular concern is the irrevocable loss of raw materials due to their increase in entropy in the linear business model.[48] Starting with the production of waste in manufacturing, the entropy increases further by mixing and diluting materials in their manufacturing assembly, followed by corrosion and wear and tear during the usage period. At the end of the life cycle, there is an exponential increase in disorder arising from the mixing of materials in landfills.[48] As a result of this directionality of the entropy law, the world's resources are effectively "lost forever".[citation needed]

Circular development is directly linked to the circular economy and aims to build a sustainable society based on recyclable and renewable resources, to protect society from waste, and to be able to form a model that no longer considering resources as infinite.[26] This new model of economic development focuses on the production of goods and services, taking into account environmental and social costs.[26] Circular development, therefore, supports the circular economy to create new societies in line with new waste management and sustainability objectives that meet the needs of citizens. It is about enabling economies and societies, in general, to become more sustainable.[citation needed]

However, critiques of the circular economy[49] suggest that proponents of the circular economy may overstate the potential benefits of the circular economy. These critiques put forward the idea that the circular economy has too many definitions to be delimited, making it an umbrella concept that, although exciting and appealing, is hard to understand and assess. Critiques mean that the literature ignores much-established knowledge. In particular, it neglects the thermodynamic principle that one can neither create nor destroy matter. Therefore, a future where waste no longer exists, where material loops are closed, and products are recycled indefinitely is, in any practical sense, impossible. They point out that a lack of inclusion of indigenous discourses from the Global South means that the conversation is less eco-centric than it depicts itself. There is a lack of clarity as to whether the circular economy is more sustainable than the linear economy and what its social benefits might be, in particular, due to diffuse contours.[50] Other issues include the increasing risks of cascading failures which are a feature of highly interdependent systems, and have potential harm to the general public. When implemented in bad faith, touted "Circular Economy" activities can often be little more than reputation and impression management for public relations purposes by large corporations and other vested interests; constituting a new form of greenwashing. It may thus not be the panacea many had hoped for.[51]

Sustainability

Intuitively, the circular economy would appear to be more sustainable than the current linear economic system. Reducing the resources used and the waste and leakage created conserves resources and helps to reduce environmental pollution. However, it is argued by some that these assumptions are simplistic and that they disregard the complexity of existing systems and their potential trade-offs. For example, the social dimension of sustainability seems to be only marginally addressed in many publications on the circular economy. Some cases that might require different or additional strategies, like purchasing new, more energy-efficient equipment. By reviewing the literature, a team of researchers from Cambridge and TU Delft showed that there are at least eight different relationship types between sustainability and the circular economy.[30] In addition, it is important to underline the innovation aspect at the heart of sustained development based on circular economy components.[52]

Scope

The circular economy can have a broad scope. Researchers have focused on different areas such as industrial applications with both product-oriented and natural resources and services,[53] practices and policies[54] to better understand the limitations that the CE currently faces, strategic management for details of the circular economy and different outcomes such as potential re-use applications[55] and waste management.[56]

The circular economy includes products, infrastructure, equipment, services[57] and buildings [58]and applies to every industry sector. It includes 'technical' resources (metals, minerals, fossil resources) and 'biological' resources (food, fibres, timber, etc.).[33] Most schools of thought advocate a shift from fossil fuels to the use of renewable energy, and emphasize the role of diversity as a characteristic of resilient and sustainable systems. The circular economy includes a discussion of the role of money and finance as part of the wider debate, and some of its pioneers have called for a revamp of economic performance measurement tools.[59] One study points out how modularization could become a cornerstone to enabling a circular economy and enhancing the sustainability of energy infrastructure.[60] One example of a circular economy model is the implementation of renting models in traditional ownership areas (e.g., electronics, clothes, furniture, transportation). By renting the same product to several clients, manufacturers can increase revenues per unit, thus decreasing the need to produce more to increase revenues. Recycling initiatives are often described as circular economy and are likely to be the most widespread models.[59]

According to a report of the organization "Circle economy" global implementation of circular economy can reduce global emissions by 22.8 billion tons, 39% of global emissions in the year 2019.[14] By 2050, 9.3 billion metric tons ofCO2 equivalent, or almost half of the global greenhouse gas emissions from the production of goods, might be reduced by implementing circular economy strategies in only five significant industries: cement, aluminum, steel, plastics, and food. That would equal to eliminating all current emissions caused by transportation.[15][16][61]

Background

As early as 1966, Kenneth Boulding raised awareness of an "open economy" with unlimited input resources and output sinks, in contrast with a "closed economy," in which resources and sinks are tied and remain as long as possible part of the economy. Boulding's essay "The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth"[62] is often cited as the first expression of the "circular economy",[63] although Boulding does not use that phrase.[citation needed]

The circular economy is grounded in the study of feedback-rich (non-linear) systems, particularly living systems.[33] The contemporary understanding of the circular economy and its practical applications to economic systems has evolved, incorporating different features and contributions from a variety of concepts sharing the idea of closed loops. Some of the relevant theoretical influences are cradle to cradle, laws of ecology (e.g., Barry Commoner § The Closing Circle), looped and performance economy (Walter R. Stahel), regenerative design, industrial ecology, biomimicry and blue economy (see section "Related concepts").[30]

The circular economy was further modelled by British environmental economists David W. Pearce and R. Kerry Turner in 1989. In Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment,[64] they pointed out that a traditional open-ended economy was developed with no built-in tendency to recycle, which was reflected by treating the environment as a waste reservoir.[65]

In the early 1990s, Tim Jackson began to create the scientific basis for this new approach to industrial production in his edited collection Clean Production Strategies,[66] including chapters from preeminent writers in the field such as Walter R Stahel, Bill Rees and Robert Constanza. At the time still called 'preventive environmental management', his follow-on book Material Concerns: Pollution, Profit and Quality of Life[67] synthesized these findings into a manifesto for change, moving industrial production away from an extractive linear system towards a more circular economy.[citation needed]

Emergence of the idea

In their 1976 research report to the European Commission, "The Potential for Substituting Manpower for Energy," Walter Stahel and Genevieve Reday sketched the vision of an economy in loops (or a circular economy) and its impact on job creation, economic competitiveness, resource savings and waste prevention. The report was published in 1982 as the book Jobs for Tomorrow: The Potential for Substituting Manpower for Energy.[68]

In 1982, Walter Stahel was awarded third prize in the Mitchell Prize competition on sustainable business models with his paper, The Product-Life Factor. The first prize went to the then US Secretary of Agriculture, the second prize to Amory and Hunter Lovins, and fourth prize to Peter Senge.[citation needed]

Considered one of the first pragmatic and credible sustainability think tanks, the main goals of Stahel's institute are to extend the working life of products, to make goods last longer, to reuse existing goods, and ultimately to prevent waste. This model emphasizes the importance of selling services rather than products, an idea referred to as the "functional service economy" and sometimes put under the wider notion of "performance economy." This model also advocates "more localization of economic activity".[69]

Promoting a circular economy was identified as a national policy in China's 11th five-year plan starting in 2006.[70] The Ellen MacArthur Foundation has more recently outlined the economic opportunity of a circular economy, bringing together complementary schools of thought in an attempt to create a coherent framework, thus giving the concept a wide exposure and appeal.[71]

Most frequently described as a framework for thinking, its supporters claim it is a coherent model that has value as part of a response to the end of the era of cheap oil and materials and, moreover, contributes to the transition to a low-carbon economy. In line with this, a circular economy can contribute to meeting the COP 21 Paris Agreement. The emissions reduction commitments made by 195 countries at the COP 21 Paris Agreement are not sufficient to limit global warming to 1.5 °C. To reach the 1.5 °C ambition, it is estimated that additional emissions reductions of 15 billion tonnes of CO2 per year need to be achieved by 2030. Circle Economy and Ecofys estimated that circular economy strategies may deliver emissions reductions that could bridge the gap by half.[72]

Moving away from the linear model

Linear "take, make, dispose" industrial processes, and the lifestyles dependent on them, use up finite reserves to create products with a finite lifespan, which end up in landfills or in incinerators. The circular approach, by contrast, takes insights from living systems. It considers that our systems should work like organisms, processing nutrients that can be fed back into the cycle—whether biological or technical—hence the "closed loop" or "regenerative" terms usually associated with it. The generic circular economy label can be applied to or claimed by several different schools of thought, but all of them gravitate around the same basic principles.[citation needed]

One prominent thinker on the topic is Walter R. Stahel, an architect, economist, and founding father of industrial sustainability. Credited with having coined the expression "Cradle to Cradle" (in contrast with "Cradle to Grave," illustrating our "Resource to Waste" way of functioning), in the late 1970s, Stahel worked on developing a "closed loop" approach to production processes, co-founding the Product-Life Institute in Geneva. In the UK, Steve D. Parker researched waste as a resource in the UK agricultural sector in 1982, developing novel closed-loop production systems. These systems mimicked and worked with the biological ecosystems they exploited.[citation needed]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Circular_economy

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk