A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Marine habitats |

|---|

|

| Coastal habitats |

| Ocean surface |

| Open ocean |

| Sea floor |

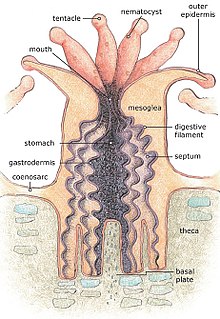

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate.[1] Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in groups.

Coral belongs to the class Anthozoa in the animal phylum Cnidaria, which includes sea anemones and jellyfish. Unlike sea anemones, corals secrete hard carbonate exoskeletons that support and protect the coral. Most reefs grow best in warm, shallow, clear, sunny and agitated water. Coral reefs first appeared 485 million years ago, at the dawn of the Early Ordovician, displacing the microbial and sponge reefs of the Cambrian.[2]

Sometimes called rainforests of the sea,[3] shallow coral reefs form some of Earth's most diverse ecosystems. They occupy less than 0.1% of the world's ocean area, about half the area of France, yet they provide a home for at least 25% of all marine species,[4][5][6][7] including fish, mollusks, worms, crustaceans, echinoderms, sponges, tunicates and other cnidarians.[8] Coral reefs flourish in ocean waters that provide few nutrients. They are most commonly found at shallow depths in tropical waters, but deep water and cold water coral reefs exist on smaller scales in other areas.

Shallow tropical coral reefs have declined by 50% since 1950, partly because they are sensitive to water conditions.[9] They are under threat from excess nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus), rising ocean heat content and acidification, overfishing (e.g., from blast fishing, cyanide fishing, spearfishing on scuba), sunscreen use,[10] and harmful land-use practices, including runoff and seeps (e.g., from injection wells and cesspools).[11][12][13]

Coral reefs deliver ecosystem services for tourism, fisheries and shoreline protection. The annual global economic value of coral reefs has been estimated at anywhere from US$30–375 billion (1997 and 2003 estimates)[14][15] to US$2.7 trillion (a 2020 estimate)[16] to US$9.9 trillion (a 2014 estimate).[17]

Though the shallow water tropical coral reefs are best known, there are also deeper water reef-forming corals, which live in colder water and in temperate seas.

Formation

Most coral reefs were formed after the Last Glacial Period when melting ice caused sea level to rise and flood continental shelves. Most coral reefs are less than 10,000 years old. As communities established themselves, the reefs grew upwards, pacing rising sea levels. Reefs that rose too slowly could become drowned, without sufficient light.[18] Coral reefs are also found in the deep sea away from continental shelves, around oceanic islands and atolls. The majority of these islands are volcanic in origin. Others have tectonic origins where plate movements lifted the deep ocean floor.

In The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs,[19] Charles Darwin set out his theory of the formation of atoll reefs, an idea he conceived during the voyage of the Beagle. He theorized that uplift and subsidence of Earth's crust under the oceans formed the atolls.[20] Darwin set out a sequence of three stages in atoll formation. A fringing reef forms around an extinct volcanic island as the island and ocean floor subside. As the subsidence continues, the fringing reef becomes a barrier reef and ultimately an atoll reef.

-

Darwin's theory starts with a volcanic island which becomes extinct

-

As the island and ocean floor subside, coral growth builds a fringing reef, often including a shallow lagoon between the land and the main reef.

-

As the subsidence continues, the fringing reef becomes a larger barrier reef further from the shore with a bigger and deeper lagoon inside.

-

Ultimately, the island sinks below the sea, and the barrier reef becomes an atoll enclosing an open lagoon.

Darwin predicted that underneath each lagoon would be a bedrock base, the remains of the original volcano.[21] Subsequent research supported this hypothesis. Darwin's theory followed from his understanding that coral polyps thrive in the tropics where the water is agitated, but can only live within a limited depth range, starting just below low tide. Where the level of the underlying earth allows, the corals grow around the coast to form fringing reefs, and can eventually grow to become a barrier reef.

Where the bottom is rising, fringing reefs can grow around the coast, but coral raised above sea level dies. If the land subsides slowly, the fringing reefs keep pace by growing upwards on a base of older, dead coral, forming a barrier reef enclosing a lagoon between the reef and the land. A barrier reef can encircle an island, and once the island sinks below sea level a roughly circular atoll of growing coral continues to keep up with the sea level, forming a central lagoon. Barrier reefs and atolls do not usually form complete circles but are broken in places by storms. Like sea level rise, a rapidly subsiding bottom can overwhelm coral growth, killing the coral and the reef, due to what is called coral drowning.[23] Corals that rely on zooxanthellae can die when the water becomes too deep for their symbionts to adequately photosynthesize, due to decreased light exposure.[24]

The two main variables determining the geomorphology, or shape, of coral reefs are the nature of the substrate on which they rest, and the history of the change in sea level relative to that substrate.

The approximately 20,000-year-old Great Barrier Reef offers an example of how coral reefs formed on continental shelves. Sea level was then 120 m (390 ft) lower than in the 21st century.[25][26] As sea level rose, the water and the corals encroached on what had been hills of the Australian coastal plain. By 13,000 years ago, sea level had risen to 60 m (200 ft) lower than at present, and many hills of the coastal plains had become continental islands. As sea level rise continued, water topped most of the continental islands. The corals could then overgrow the hills, forming cays and reefs. Sea level on the Great Barrier Reef has not changed significantly in the last 6,000 years.[26] The age of living reef structure is estimated to be between 6,000 and 8,000 years.[27] Although the Great Barrier Reef formed along a continental shelf, and not around a volcanic island, Darwin's principles apply. Development stopped at the barrier reef stage, since Australia is not about to submerge. It formed the world's largest barrier reef, 300–1,000 m (980–3,280 ft) from shore, stretching for 2,000 km (1,200 mi).[28]

Healthy tropical coral reefs grow horizontally from 1 to 3 cm (0.39 to 1.18 in) per year, and grow vertically anywhere from 1 to 25 cm (0.39 to 9.84 in) per year; however, they grow only at depths shallower than 150 m (490 ft) because of their need for sunlight, and cannot grow above sea level.[29]

Material

As the name implies, coral reefs are made up of coral skeletons from mostly intact coral colonies. As other chemical elements present in corals become incorporated into the calcium carbonate deposits, aragonite is formed. However, shell fragments and the remains of coralline algae such as the green-segmented genus Halimeda can add to the reef's ability to withstand damage from storms and other threats. Such mixtures are visible in structures such as Eniwetok Atoll.[30][page needed]

In the geologic past

The times of maximum reef development were in the Middle Cambrian (513–501 Ma), Devonian (416–359 Ma) and Carboniferous (359–299 Ma), owing to extinct order Rugosa corals, and Late Cretaceous (100–66 Ma) and Neogene (23 Ma–present), owing to order Scleractinia corals.[31]

Not all reefs in the past were formed by corals: those in the Early Cambrian (542–513 Ma) resulted from calcareous algae and archaeocyathids (small animals with conical shape, probably related to sponges) and in the Late Cretaceous (100–66 Ma), when reefs formed by a group of bivalves called rudists existed; one of the valves formed the main conical structure and the other, much smaller valve acted as a cap.[32]

Measurements of the oxygen isotopic composition of the aragonitic skeleton of coral reefs, such as Porites, can indicate changes in sea surface temperature and sea surface salinity conditions during the growth of the coral. This technique is often used by climate scientists to infer a region's paleoclimate.[33]

Types

Since Darwin's identification of the three classical reef formations – the fringing reef around a volcanic island becoming a barrier reef and then an atoll[34] – scientists have identified further reef types. While some sources find only three,[35][36] Thomas lists "Four major forms of large-scale coral reefs" – the fringing reef, barrier reef, atoll and table reef based on Stoddart, D.R. (1969).[37][38] Spalding et al. list four main reef types that can be clearly illustrated – the fringing reef, barrier reef, atoll, and "bank or platform reef"—and notes that many other structures exist which do not conform easily to strict definitions, including the "patch reef".[39]

Fringing reef

A fringing reef, also called a shore reef,[40] is directly attached to a shore,[41] or borders it with an intervening narrow, shallow channel or lagoon.[42] It is the most common reef type.[42] Fringing reefs follow coastlines and can extend for many kilometres.[43] They are usually less than 100 metres wide, but some are hundreds of metres wide.[44] Fringing reefs are initially formed on the shore at the low water level and expand seawards as they grow in size. The final width depends on where the sea bed begins to drop steeply. The surface of the fringe reef generally remains at the same height: just below the waterline. In older fringing reefs, whose outer regions pushed far out into the sea, the inner part is deepened by erosion and eventually forms a lagoon.[45] Fringing reef lagoons can become over 100 metres wide and several metres deep. Like the fringing reef itself, they run parallel to the coast. The fringing reefs of the Red Sea are "some of the best developed in the world" and occur along all its shores except off sandy bays.[46]

Barrier reef

Barrier reefs are separated from a mainland or island shore by a deep channel or lagoon.[42] They resemble the later stages of a fringing reef with its lagoon but differ from the latter mainly in size and origin. Their lagoons can be several kilometres wide and 30 to 70 metres deep. Above all, the offshore outer reef edge formed in open water rather than next to a shoreline. Like an atoll, it is thought that these reefs are formed either as the seabed lowered or sea level rose. Formation takes considerably longer than for a fringing reef, thus barrier reefs are much rarer.

The best known and largest example of a barrier reef is the Australian Great Barrier Reef.[42][47] Other major examples are the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System and the New Caledonian Barrier Reef.[47] Barrier reefs are also found on the coasts of Providencia,[47] Mayotte, the Gambier Islands, on the southeast coast of Kalimantan, on parts of the coast of Sulawesi, southeastern New Guinea and the south coast of the Louisiade Archipelago.

Platform reef

Platform reefs, variously called bank or table reefs, can form on the continental shelf, as well as in the open ocean, in fact anywhere where the seabed rises close enough to the surface of the ocean to enable the growth of zooxanthemic, reef-forming corals.[48] Platform reefs are found in the southern Great Barrier Reef, the Swain[49] and Capricorn Group[50] on the continental shelf, about 100–200 km from the coast. Some platform reefs of the northern Mascarenes are several thousand kilometres from the mainland. Unlike fringing and barrier reefs which extend only seaward, platform reefs grow in all directions.[48] They are variable in size, ranging from a few hundred metres to many kilometres across. Their usual shape is oval to elongated. Parts of these reefs can reach the surface and form sandbanks and small islands around which may form fringing reefs. A lagoon may form In the middle of a platform reef.

Platform reefs are typically situated within atolls, where they adopt the name "patch reefs" and often span a diameter of just a few dozen meters. In instances where platform reefs develop along elongated structures, such as old and weathered barrier reefs, they tend to arrange themselves in a linear formation. This is the case, for example, on the east coast of the Red Sea near Jeddah. In old platform reefs, the inner part can be so heavily eroded that it forms a pseudo-atoll.[48] These can be distinguished from real atolls only by detailed investigation, possibly including core drilling. Some platform reefs of the Laccadives are U-shaped, due to wind and water flow.

Atoll

Atolls or atoll reefs are a more or less circular or continuous barrier reef that extends all the way around a lagoon without a central island.[51] They are usually formed from fringing reefs around volcanic islands.[42] Over time, the island erodes away and sinks below sea level.[42] Atolls may also be formed by the sinking of the seabed or rising of the sea level. A ring of reefs results, which enclose a lagoon. Atolls are numerous in the South Pacific, where they usually occur in mid-ocean, for example, in the Caroline Islands, the Cook Islands, French Polynesia, the Marshall Islands and Micronesia.[47]

Atolls are found in the Indian Ocean, for example, in the Maldives, the Chagos Islands, the Seychelles and around Cocos Island.[47] The entire Maldives consist of 26 atolls.[52]

Other reef types or variants

- Apron reef – short reef resembling a fringing reef, but more sloped; extending out and downward from a point or peninsular shore. The initial stage of a fringing reef.[40]

- Bank reef – isolated, flat-topped reef larger than a patch reef and usually on mid-shelf regions and linear or semi-circular in shape; a type of platform reef.[47]

- Patch reef – common, isolated, comparatively small reef outcrop, usually within a lagoon or embayment, often circular and surrounded by sand or seagrass. Can be considered as a type of platform reef [who?] or as features of fringing reefs, atolls and barrier reefs.[47] The patches may be surrounded by a ring of reduced seagrass cover referred to as a grazing halo.[53]

- Ribbon reef – long, narrow, possibly winding reef, usually associated with an atoll lagoon. Also called a shelf-edge reef or sill reef.[40]

- Drying reef – a part of a reef which is above water at low tide but submerged at high tide[54]

- Habili – reef specific to the Red Sea; does not reach near enough to the surface to cause visible surf; may be a hazard to ships (from the Arabic for "unborn")

- Microatoll – community of species of corals; vertical growth limited by average tidal height; growth morphologies offer a low-resolution record of patterns of sea level change; fossilized remains can be dated using radioactive carbon dating and have been used to reconstruct Holocene sea levels[55]

- Cays – small, low-elevation, sandy islands formed on the surface of coral reefs from eroded material that piles up, forming an area above sea level; can be stabilized by plants to become habitable; occur in tropical environments throughout the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans (including the Caribbean and on the Great Barrier Reef and Belize Barrier Reef), where they provide habitable and agricultural land

- Seamount or guyot – formed when a coral reef on a volcanic island subsides; tops of seamounts are rounded and guyots are flat; flat tops of guyots, or tablemounts, are due to erosion by waves, winds, and atmospheric processes

Zones

Coral reef ecosystems contain distinct zones that host different kinds of habitats. Usually, three major zones are recognized: the fore reef, reef crest, and the back reef (frequently referred to as the reef lagoon).

The three zones are physically and ecologically interconnected. Reef life and oceanic processes create opportunities for the exchange of seawater, sediments, nutrients and marine life.

Most coral reefs exist in waters less than 50 m deep.[56] Some inhabit tropical continental shelves where cool, nutrient-rich upwelling does not occur, such as the Great Barrier Reef. Others are found in the deep ocean surrounding islands or as atolls, such as in the Maldives. The reefs surrounding islands form when islands subside into the ocean, and atolls form when an island subsides below the surface of the sea.

Alternatively, Moyle and Cech distinguish six zones, though most reefs possess only some of the zones.[57]

The reef surface is the shallowest part of the reef. It is subject to surge and tides. When waves pass over shallow areas, they shoal, as shown in the adjacent diagram. This means the water is often agitated. These are the precise condition under which corals flourish. The light is sufficient for photosynthesis by the symbiotic zooxanthellae, and agitated water brings plankton to feed the coral.

The off-reef floor is the shallow sea floor surrounding a reef. This zone occurs next to reefs on continental shelves. Reefs around tropical islands and atolls drop abruptly to great depths and do not have such a floor. Usually sandy, the floor often supports seagrass meadows which are important foraging areas for reef fish.

The reef drop-off is, for its first 50 m, habitat for reef fish who find shelter on the cliff face and plankton in the water nearby. The drop-off zone applies mainly to the reefs surrounding oceanic islands and atolls.

The reef face is the zone above the reef floor or the reef drop-off. This zone is often the reef's most diverse area. Coral and calcareous algae provide complex habitats and areas that offer protection, such as cracks and crevices. Invertebrates and epiphytic algae provide much of the food for other organisms.[57] A common feature on this forereef zone is spur and groove formations that serve to transport sediment downslope.

The reef flat is the sandy-bottomed flat, which can be behind the main reef, containing chunks of coral. This zone may border a lagoon and serve as a protective area, or it may lie between the reef and the shore, and in this case is a flat, rocky area. Fish tend to prefer it when it is present.[57]

The reef lagoon is an entirely enclosed region, which creates an area less affected by wave action and often contains small reef patches.[57]

However, the topography of coral reefs is constantly changing. Each reef is made up of irregular patches of algae, sessile invertebrates, and bare rock and sand. The size, shape and relative abundance of these patches change from year to year in response to the various factors that favor one type of patch over another. Growing coral, for example, produces constant change in the fine structure of reefs. On a larger scale, tropical storms may knock out large sections of reef and cause boulders on sandy areas to move.[58]

Locations

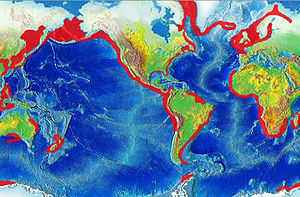

Coral reefs are estimated to cover 284,300 km2 (109,800 sq mi),[59] just under 0.1% of the oceans' surface area. The Indo-Pacific region (including the Red Sea, Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia and the Pacific) account for 91.9% of this total. Southeast Asia accounts for 32.3% of that figure, while the Pacific including Australia accounts for 40.8%. Atlantic and Caribbean coral reefs account for 7.6%.[5]

Although corals exist both in temperate and tropical waters, shallow-water reefs form only in a zone extending from approximately 30° N to 30° S of the equator. Tropical corals do not grow at depths of over 50 meters (160 ft). The optimum temperature for most coral reefs is 26–27 °C (79–81 °F), and few reefs exist in waters below 18 °C (64 °F).[60] When the net production by reef building corals no longer keeps pace with relative sea level and the reef structure permanently drowns a Darwin Point is reached. One such point exists at the northwestern end of the Hawaiian Archipelago; see Evolution of Hawaiian volcanoes#Coral atoll stage.[61][62]

However, reefs in the Persian Gulf have adapted to temperatures of 13 °C (55 °F) in winter and 38 °C (100 °F) in summer.[63] 37 species of scleractinian corals inhabit such an environment around Larak Island.[64]

Deep-water coral inhabits greater depths and colder temperatures at much higher latitudes, as far north as Norway.[65] Although deep water corals can form reefs, little is known about them.

The northernmost coral reef on Earth is located near Eilat, Israel.[66] Coral reefs are rare along the west coasts of the Americas and Africa, due primarily to upwelling and strong cold coastal currents that reduce water temperatures in these areas (the Humboldt, Benguela, and Canary Currents, respectively).[67] Corals are seldom found along the coastline of South Asia—from the eastern tip of India (Chennai) to the Bangladesh and Myanmar borders[5]—as well as along the coasts of northeastern South America and Bangladesh, due to the freshwater release from the Amazon and Ganges Rivers respectively.

Significant coral reefs include:

- The Great Barrier Reef—largest, comprising over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over 2,600 kilometers (1,600 mi) off Queensland, Australia

- The Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System—second largest, stretching 1,000 kilometers (620 mi) from Isla Contoy at the tip of the Yucatán Peninsula down to the Bay Islands of Honduras

- The New Caledonia Barrier Reef—second longest double barrier reef, covering 1,500 kilometers (930 mi)

- The Andros, Bahamas Barrier Reef—third largest, following the east coast of Andros Island, Bahamas, between Andros and Nassau

- The Red Sea—includes 6,000-year-old fringing reefs located along a 2,000 km (1,240 mi) coastline

- The Florida Reef Tract—largest continental US reef and the third-largest coral barrier reef, extends from Soldier Key, located in Biscayne Bay, to the Dry Tortugas in the Gulf of Mexico[68]

- Blake Plateau has the world's largest known deep-water coral reef, comprising a 6.4 million acre reef that stretches from Miami to Charleston, S. C. Its discovery was announced in January 2024.[69]

- Pulley Ridge—deepest photosynthetic coral reef, Florida

- Numerous reefs around the Maldives

- The Philippines coral reef area, the second-largest in Southeast Asia, is estimated at 26,000 square kilometres. 915 reef fish species and more than 400 scleractinian coral species, 12 of which are endemic are found there.

- The Raja Ampat Islands in Indonesia's West Papua province offer the highest known marine diversity.[70]

- Bermuda is known for its northernmost coral reef system, located at 32°24′N 64°48′W / 32.4°N 64.8°W. The presence of coral reefs at this high latitude is due to the proximity of the Gulf Stream. Bermuda coral species represent a subset of those found in the greater Caribbean.[71]

- The world's northernmost individual coral reef is located in the Finlayson Channel, in the inside passage of British Columbia, Canada.[72]

- The world's southernmost coral reef is at Lord Howe Island, in the Pacific Ocean off the east coast of Australia.

Coral

When alive, corals are colonies of small animals embedded in calcium carbonate shells. Coral heads consist of accumulations of individual animals called polyps, arranged in diverse shapes.[73] Polyps are usually tiny, but they can range in size from a pinhead to 12 inches (30 cm) across.

Reef-building or hermatypic corals live only in the photic zone (above 70 m), the depth to which sufficient sunlight penetrates the water.[74]

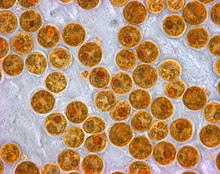

Zooxanthellae

Coral polyps do not photosynthesize, but have a symbiotic relationship with microscopic algae (dinoflagellates) of the genus Symbiodinium, commonly referred to as zooxanthellae. These organisms live within the polyps' tissues and provide organic nutrients that nourish the polyp in the form of glucose, glycerol and amino acids.[75] Because of this relationship, coral reefs grow much faster in clear water, which admits more sunlight. Without their symbionts, coral growth would be too slow to form significant reef structures. Corals get up to 90% of their nutrients from their symbionts.[76] In return, as an example of mutualism, the corals shelter the zooxanthellae, averaging one million for every cubic centimetre of coral, and provide a constant supply of the carbon dioxide they need for photosynthesis.

The varying pigments in different species of zooxanthellae give them an overall brown or golden-brown appearance and give brown corals their colors. Other pigments such as reds, blues, greens, etc. come from colored proteins made by the coral animals. Coral that loses a large fraction of its zooxanthellae becomes white (or sometimes pastel shades in corals that are pigmented with their own proteins) and is said to be bleached, a condition which, unless corrected, can kill the coral.

There are eight clades of Symbiodinium phylotypes. Most research has been conducted on clades A–D. Each clade contributes their own benefits as well as less compatible attributes to the survival of their coral hosts. Each photosynthetic organism has a specific level of sensitivity to photodamage to compounds needed for survival, such as proteins. Rates of regeneration and replication determine the organism's ability to survive. Phylotype A is found more in the shallow waters. It is able to produce mycosporine-like amino acids that are UV resistant, using a derivative of glycerin to absorb the UV radiation and allowing them to better adapt to warmer water temperatures. In the event of UV or thermal damage, if and when repair occurs, it will increase the likelihood of survival of the host and symbiont. This leads to the idea that, evolutionarily, clade A is more UV resistant and thermally resistant than the other clades.[77]

Clades B and C are found more frequently in deeper water, which may explain their higher vulnerability to increased temperatures. Terrestrial plants that receive less sunlight because they are found in the undergrowth are analogous to clades B, C, and D. Since clades B through D are found at deeper depths, they require an elevated light absorption rate to be able to synthesize as much energy. With elevated absorption rates at UV wavelengths, these phylotypes are more prone to coral bleaching versus the shallow clade A.

Clade D has been observed to be high temperature-tolerant, and has a higher rate of survival than clades B and C during modern bleaching events.[77]

Skeleton

Reefs grow as polyps and other organisms deposit calcium carbonate,[78][79] the basis of coral, as a skeletal structure beneath and around themselves, pushing the coral head's top upwards and outwards.[80] Waves, grazing fish (such as parrotfish), sea urchins, sponges and other forces and organisms act as bioeroders, breaking down coral skeletons into fragments that settle into spaces in the reef structure or form sandy bottoms in associated reef lagoons.

Typical shapes for coral species are named by their resemblance to terrestrial objects such as wrinkled brains, cabbages, table tops, antlers, wire strands and pillars. These shapes can depend on the life history of the coral, like light exposure and wave action,[81] and events such as breakages.[82]

Reproduction

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Corals reproduce both sexually and asexually. An individual polyp uses both reproductive modes within its lifetime. Corals reproduce sexually by either internal or external fertilization. The reproductive cells are found on the mesenteries, membranes that radiate inward from the layer of tissue that lines the stomach cavity. Some mature adult corals are hermaphroditic; others are exclusively male or female. A few species change sex as they grow.

Internally fertilized eggs develop in the polyp for a period ranging from days to weeks. Subsequent development produces a tiny larva, known as a planula. Externally fertilized eggs develop during synchronized spawning. Polyps across a reef simultaneously release eggs and sperm into the water en masse. Spawn disperse over a large area. The timing of spawning depends on time of year, water temperature, and tidal and lunar cycles. Spawning is most successful given little variation between high and low tide. The less water movement, the better the chance for fertilization. The release of eggs or planula usually occurs at night and is sometimes in phase with the lunar cycle (three to six days after a full moon).[84][85][86]

The period from release to settlement lasts only a few days, but some planulae can survive afloat for several weeks. During this process, the larvae may use several different cues to find a suitable location for settlement. At long distances sounds from existing reefs are likely important,[87] while at short distances chemical compounds become important.[88] The larvae are vulnerable to predation and environmental conditions. The lucky few planulae that successfully attach to substrate then compete for food and space.[citation needed]

Gallery of reef-building corals

|

|

Other reef builders

Corals are the most prodigious reef-builders. However many other organisms living in the reef community contribute skeletal calcium carbonate in the same manner as corals. These include coralline algae, some sponges and bivalves.[90] Reefs are always built by the combined efforts of these different phyla, with different organisms leading reef-building in different geological periods.[91]

Coralline algae

Coralline algae are important contributors to reef structure. Although their mineral deposition rates are much slower than corals, they are more tolerant of rough wave-action, and so help to create a protective crust over those parts of the reef subjected to the greatest forces by waves, such as the reef front facing the open ocean. They also strengthen the reef structure by depositing limestone in sheets over the reef surface.[citation needed]

Sponges

"Sclerosponge" is the descriptive name for all Porifera that build reefs. In the early Cambrian period, Archaeocyatha sponges were the world's first reef-building organisms, and sponges were the only reef-builders until the Ordovician. Sclerosponges still assist corals building modern reefs, but like coralline algae are much slower-growing than corals and their contribution is (usually) minor.[citation needed]

In the northern Pacific Ocean cloud sponges still create deep-water mineral-structures without corals, although the structures are not recognizable from the surface like tropical reefs. They are the only extant organisms known to build reef-like structures in cold water.[citation needed]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Coral_reefs

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk