A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

The history of independent India or history of Republic of India began when the country became an independent sovereign state within the British Commonwealth on 15 August 1947. Direct administration by the British, which began in 1858, affected a political and economic unification of the subcontinent. When British rule came to an end in 1947, the subcontinent was partitioned along religious lines into two separate countries—India, with a majority of Hindus, and Pakistan, with a majority of Muslims.[1] Concurrently the Muslim-majority northwest and east of British India was separated into the Dominion of Pakistan, by the Partition of India. The partition led to a population transfer of more than 10 million people between India and Pakistan and the death of about one million people. Indian National Congress leader Jawaharlal Nehru became the first Prime Minister of India, but the leader most associated with the independence struggle, Mahatma Gandhi, accepted no office. The constitution adopted in 1950 made India a democratic republic with Westminster style parliamentary system of government, both at federal and state level respectively. The democracy has been sustained since then. India's sustained democratic freedoms are unique among the world's newly independent states.[2]

The country has faced religious violence, naxalism, terrorism and regional separatist insurgencies. India has unresolved territorial disputes with China which escalated into a war in 1962 and 1967, and with Pakistan which resulted in wars in 1947, 1965, 1971 and 1999. India was neutral in the Cold War, and was a leader in the Non-Aligned Movement. However, it made a loose alliance with the Soviet Union from 1971, when Pakistan was allied with the United States and the People's Republic of China.

| History of India |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

India is a nuclear-weapon state, having conducted its first nuclear test in 1974, followed by another five tests in 1998. From the 1950s to the 1980s, India followed socialist-inspired policies. The economy was influenced by extensive regulation, protectionism and public ownership, leading to pervasive corruption and slow economic growth. Since 1991, India has pursued more economic liberalisation. Today, India is the third largest and one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

From being a relatively struggling country in its formative years,[3] the Republic of India has emerged as a fast growing G20 major economy.[4][5] India has sometimes been referred to as a great power and a potential superpower given its large and growing economy, military and population.[6][7][8][9]

1947–1950: Dominion of India

Independent India's first years were marked with turbulent events—a massive exchange of population with Pakistan, the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 and the integration of over 500 princely states to form a united nation.[10] Vallabhbhai Patel, Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi also ensured that the constitution of independent India would be secular.[11]

Partition of India

The partition of India was outlined in the Indian Independence Act 1947. It led to the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: India and Pakistan.[12][13] The change of political borders notably included the division of two provinces of British India,[a] Bengal and Punjab.[14] The majority Muslim districts in these provinces were awarded to Pakistan and the majority non-Muslim to India. The other assets that were divided included the British Indian Army, the Royal Indian Navy, the Royal Indian Air Force, the Indian Civil Service, the railways, and the central treasury. Self-governing independent Pakistan and India legally came into existence at midnight on 14 and 15 August 1947 respectively.

The partition caused large-scale loss of life and an unprecedented migration between the two dominions.[15] Among refugees who survived, it solidified the belief that safety lay among co-religionists. In the instance of Pakistan, it made palpable a hitherto only-imagined refuge for the Muslims of British India.[16] The migrations took place hastily and with little warning. It is thought that between 14 million and 18 million people moved, and perhaps more. Excess mortality during the period of the partition is usually estimated to have been around one million.[17] The violent nature of the partition created an atmosphere of hostility and suspicion between India and Pakistan that affects their relationship to this day.

An estimated 3.5 million[18] Hindus and Sikhs living in West Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Baluchistan, East Bengal and Sind migrated to India in fear of domination and suppression in Muslim Pakistan. Communal violence killed an estimated one million Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, and gravely destabilised both dominions along their Punjab and Bengal boundaries, and the cities of Calcutta, Delhi and Lahore. The violence was stopped by early September owing to the co-operative efforts of both Indian and Pakistani leaders, and especially due to the efforts of Mohandas Gandhi, the leader of the Indian freedom struggle, who undertook a fast-unto-death in Calcutta and later in Delhi to calm people and emphasise peace despite the threat to his life. Both governments constructed large relief camps for incoming and leaving refugees, and the Indian Army was mobilised to provide humanitarian assistance on a massive scale.

I find no parallel in history for a body of converts and their descendants claiming to be a nation apart from the parent stock.

The assassination of Mohandas Gandhi on 30 January 1948 was carried out by Nathuram Godse, who held him responsible for partition and charged that Mohandas Gandhi was appeasing Muslims. More than one million people flooded the streets of Delhi to follow the procession to cremation grounds and pay their last respects.

In 1949, India recorded almost 1 million Hindu refugees into West Bengal and other states from East Pakistan, owing to communal violence, intimidation, and repression from Muslim authorities. The plight of the refugees outraged Hindus and Indian nationalists, and the refugee population drained the resources of Indian states, who were unable to absorb them. While not ruling out war, Prime Minister Nehru and Sardar Patel invited Liaquat Ali Khan for talks in Delhi. Although many Indians termed this appeasement, Nehru signed a pact with Liaquat Ali Khan that pledged both nations to the protection of minorities and creation of minority commissions. Although opposed to the principle, Patel decided to back this pact for the sake of peace, and played a critical role in garnering support from West Bengal and across India, and enforcing the provisions of the pact. Khan and Nehru also signed a trade agreement, and committed to resolving bilateral disputes through peaceful means. Steadily, hundreds of thousands of Hindus returned to East Pakistan, but the thaw in relations did not last long, primarily owing to the Kashmir dispute.

| |||||

Integration of princely statesedit

In July 1946, Jawaharlal Nehru pointedly observed that no princely state could prevail militarily against the army of independent India.[20] In January 1947, Nehru said that independent India would not accept the divine right of kings.[21] In May 1947, he declared that any princely state which refused to join the Constituent Assembly would be treated as an enemy state.[22] British India consisted of 17 provinces, which existed alongside 565 princely states. The provinces were given to India or Pakistan, in two particular cases—Punjab and Bengal—after being partitioned. The princes of the princely states, however, were given the right to either remain independent or accede to either dominion. Thus India's leaders were faced with the prospect of inheriting a fragmented country with independent states and kingdoms dispersed across the mainland. Under the leadership of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the new Government of India employed political negotiations backed with the option (and, on several occasions, the use) of military action to ensure the primacy of the central government and of the Constitution then being drafted. Sardar Patel and V. P. Menon convinced the rulers of princely states contiguous to India to accede to India. Many rights and privileges of the rulers of the princely states, especially their personal estates and privy purses, were guaranteed to convince them to accede. Some of them were made Rajpramukh (governor) and Uprajpramukh (deputy governor) of the merged states. Many small princely states were merged to form viable administrative states such as Saurashra, PEPSU, Vindhya Pradesh and Madhya Bharat. Some princely states such as Tripura and Manipur acceded later in 1949.

There were three states that proved more difficult to integrate than others:

- Junagadh (Hindu-majority state with a Muslim Nawab)—a December 1947 plebiscite resulted in a 99% vote[23] to merge with India, annulling the controversial accession to Pakistan, which was made by the Nawab against the wishes of the people of the state who were overwhelmingly Hindu and despite Junagadh not being contiguous with Pakistan.

- Hyderabad (Hindu-majority state with a Muslim nizam)—Patel ordered the Indian army to depose the government of the Nizam, code-named Operation Polo, after the failure of negotiations, which was done between 13 and 29 September 1948. It was incorporated as a state of India the next year.

- The state of Jammu and Kashmir (a Muslim-majority state with a Hindu king) in the far north of the subcontinent quickly became a source of controversy that erupted into the First Indo-Pakistani War which lasted from 1947 to 1949. Eventually, a United Nations-overseen ceasefire was agreed that left India in control of two-thirds of the contested region. Jawaharlal Nehru initially agreed to Mountbatten's proposal that a plebiscite be held in the entire state as soon as hostilities ceased, and a UN-sponsored cease-fire was agreed to by both parties on 1 January 1949. No statewide plebiscite was held, however, for in 1954, after Pakistan began to receive arms from the United States, Nehru withdrew his support. The Indian Constitution came into force in Kashmir on 26 January 1950 with special clauses for the state.

Constitutionedit

The Constitution of India was adopted by the Constituent Assembly on 26 November 1949 and became effective on 26 January 1950.[24] The constitution replaced the Government of India Act 1935 as the country's fundamental governing document, and the Dominion of India became the Republic of India. To ensure constitutional autochthony, its framers repealed prior acts of the British parliament in Article 395.[25] The constitution declares India a sovereign, socialist, secular,[26] and democratic republic, assures its citizens justice, equality, and liberty, and endeavours to promote fraternity.[27] Key features of the constitution were Universal suffrage for all adults,Westminster style parliamentary system of government at the federal and state level, and independent judiciary.[28] The constitution also required the Union Government and the States and Territories of India to set reserved quotas or seats, at particular percentage in Education Admissions, Employments, Political Bodies, Promotions, etc., for "socially and educationally backward citizens."[29][30] The constitution has had more than 100 amendments since it was enacted.[31]

India celebrates its constitution on 26 January as Republic Day.[32]

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948edit

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948 was fought between India and Pakistan over the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu from 1947 to 1948. It was the first of four Indo-Pakistan Wars fought between the two newly independent nations. Pakistan precipitated the war a few weeks after independence by launching tribal lashkar (militia) from Waziristan,[33] in an effort to secure Kashmir, the future of which hung in the balance. A United Nations-mediated ceasefire took place on 5 January 1949.

Indian losses in the war totalled 1,104 killed and 3,154 wounded;[34] Pakistani, about 6,000 killed and 14,000 wounded.[35] Neutral assessments state India emerged victorious as it successfully defended the majority of the contested territory.[36][37][38][39][40]

Governance and politicsedit

India held its first national elections under the Constitution in 1952, where a turnout of over 60% was recorded. The Indian National Congress won an overwhelming majority, and Jawaharlal Nehru began a second term as prime minister. President Prasad was also elected to a second term by the electoral college of the first Parliament of India.[41]

Nehru administration (1952–1964)edit

Nehru can be regarded as the founder of the modern Indian state. Parekh attributes this to the national philosophy Nehru formulated for India. For him, modernisation was the national philosophy, with seven goals: national unity, parliamentary democracy, industrialisation, socialism, development of the scientific temper, and non-alignment. In Parekh's opinion, the philosophy and the policies that resulted from this benefited a large section of society such as public sector workers, industrial houses, and middle and upper peasantry. However, it failed to benefit or satisfy the urban and rural poor, the unemployed and the Hindu fundamentalists.[42]

The death of Vallabhbhai Patel in 1950 left Nehru as the sole remaining iconic national leader, and soon the situation became such that Nehru could implement his vision for India without hindrance.[43]

Nehru implemented economic policies based on import substitution industrialisation and advocated a mixed economy where the government-controlled public sector would co-exist with the private sector.[44] He believed the establishment of basic and heavy industry was fundamental to the development and modernisation of the Indian economy. The government, therefore, directed investment primarily into key public sector industries—steel, iron, coal, and power—promoting their development with subsidies and protectionist policies.[45]

Nehru led the Congress to further election victories in 1957 and 1962. During his tenure, the Indian Parliament passed extensive reforms that increased the legal rights of women in Hindu society,[46][47][48][49] and further legislated against caste discrimination and untouchability.[citation needed] Nehru advocated a strong initiative to enroll India's children to complete primary education, and thousands of schools, colleges and institutions of advanced learning, such as the Indian Institutes of Technology, were founded across the nation.[50] Nehru advocated a socialist model for the economy of India. After India achieved independence, a formal model of planning was adopted, and accordingly the Planning Commission, reporting directly to the Prime Minister, was established in 1950, with Nehru as the chairman. The commission was tasked with formulating Five-Year Plans for economic development which were shaped by the Soviet model based on centralised and integrated national economic programs[51]—no taxation for Indian farmers, minimum wage and benefits for blue-collar workers, and the nationalisation of heavy industries such as steel, aviation, shipping, electricity, and mining. Village common lands were seized, and an extensive public works and industrialisation campaign resulted in the construction of major dams, irrigation canals, roads, thermal and hydroelectric power stations, and many more.[citation needed]

States reorganisationedit

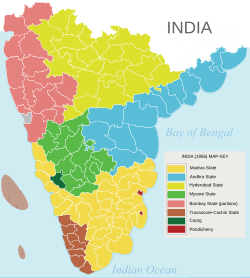

Potti Sreeramulu's fast-unto-death, and consequent death for the demand of an Andhra State in 1952 sparked a major re-shaping of the Indian Union. Nehru appointed the States Re-organisation Commission, upon whose recommendations the States Reorganisation Act was passed in 1956. Old states were dissolved and new states created on the lines of shared linguistic and ethnic demographics. The separation of Kerala and the Telugu-speaking regions of Madras State enabled the creation of an exclusively Tamil-speaking state of Tamil Nadu. On 1 May 1960, the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat were created out of the bilingual Bombay State, and on 1 November 1966, the larger Punjab state was divided into the smaller, Punjabi-speaking Punjab and Haryanvi-speaking Haryana states.[52]

Development of a multi-party systemedit

In pre-independence India, the main parties were the Congress and the Muslim league.There were also many other parties such as the Hindu mahasabha, Justice party, the Akali dal, the Communist party etc. during this period with limited or regional appeal. With the eclipse of the Muslim league due to partition, the Congress party was able to dominate Indian politics during the 1950s.This started breaking down during the 60s and 70s.This period saw formation of many new parties.These included those founded by former congress leaders such as the Swatantra party, many Socialist leaning parties, and the Bharatiya Jan Sangh, the political arm of the Hindu nationalist RSS.[53]

Swatantra Partyedit

On 4 June 1959, shortly after the Nagpur session of the Indian National Congress, C. Rajagopalachari,[54] along with Murari Vaidya of the newly established Forum of Free Enterprise (FFE)[55] and Minoo Masani, a classical liberal and critic of socialist leaning Nehru, announced the formation of the new Swatantra Party at a meeting in Madras.[56] Conceived by disgruntled heads of former princely states such as the Raja of Ramgarh, the Maharaja of Kalahandi and the Maharajadhiraja of Darbhanga, the party was conservative in character.[57][58] Later, N. G. Ranga, K. M. Munshi, Field Marshal K. M. Cariappa and the Maharaja of Patiala joined the effort.[58] Rajagopalachari, Masani and Ranga also tried but failed to involve Jayaprakash Narayan in the initiative.[59]

In his short essay "Our Democracy", Rajagopalachari argued the necessity of a right-wing alternative to the Congress: "since ... the Congress Party has swung to the Left, what is wanted is not an ultra or outer-Left viz. the CPI or the Praja Socialist Party, PSP, but a strong and articulate Right."[57] Rajagopalachari also said the opposition must: "operate not privately and behind the closed doors of the party meeting, but openly and periodically through the electorate."[57] He outlined the goals of the Swatantra Party through twenty-one "fundamental principles" in the foundation document.[60] The party stood for equality and opposed government control over the private sector.[61][62] Rajagopalachari sharply criticised the bureaucracy and coined the term "licence-permit Raj" to describe Nehru's elaborate system of permissions and licences required for an individual to set up a private enterprise. Rajagopalachari's personality became a rallying point for the party.[57]

Rajagopalachari's efforts to build an anti-Congress front led to a patch-up with his former adversary C. N. Annadurai of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam.[63] During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Annadurai grew close to Rajagopalachari and sought an alliance with the Swatantra Party for the 1962 Madras Legislative Assembly elections. Although there were occasional electoral pacts between the Swatantra Party and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), Rajagopalachari remained non-committal on a formal tie-up with the DMK due to its existing alliance with Communists whom he dreaded.[64] The Swatantra Party contested 94 seats in the Madras state assembly elections and won six[65] as well as won 18 parliamentary seats in the 1962 Lok Sabha elections.[66]

Foreign policy and military conflictsedit

Nehru's foreign policy was the inspiration of the Non-Aligned Movement, of which India was a co-founder. Nehru maintained friendly relations with both the United States and the Soviet Union, and encouraged the People's Republic of China to join the global community of nations. In 1956, when the Suez Canal Company was seized by the Egyptian government, an international conference voted 18–4 to take action against Egypt. India was one of the four backers of Egypt, along with Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and the USSR. India had opposed the partition of Palestine and the 1956 invasion of the Sinai by Israel, the United Kingdom and France, but did not oppose the Chinese direct control over Tibet,[67] and the suppression of a pro-democracy movement in Hungary by the Soviet Union. Although Nehru disavowed nuclear ambitions for India, Canada and France aided India in the development of nuclear power stations for electricity. India also negotiated an agreement in 1960 with Pakistan on the just use of the waters of seven rivers shared by the countries. Nehru had visited Pakistan in 1953, but owing to political turmoil in Pakistan, no headway was made on the Kashmir dispute.[68]

India has fought a total of four wars/military conflicts with its neighbouring rival state Pakistan, two in this period. In the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, fought over the disputed territory of Kashmir, Pakistan captured one-third of Kashmir (which India claims as its territory), and India captured three-fifths (which Pakistan claims as its territory). In the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, India attacked Pakistan on all fronts by crossing the international border after attempts by Pakistani troops to infiltrate Indian-controlled Kashmir by crossing the de facto border between India and Pakistan in Kashmir.

In 1961, after continual petitions for a peaceful handover, India invaded and annexed the Portuguese colony of Goa on the west coast of India.[69]

In 1962 China and India engaged in the brief Sino-Indian War over the border in the Himalayas. The war was a complete rout for the Indians and led to a refocusing on arms build-up and an improvement in relations with the United States. China withdrew from disputed territory in the contested Chinese South Tibet and Indian North-East Frontier Agency that it crossed during the war. India disputes China's sovereignty over the smaller Aksai Chin territory that it controls on the western part of the Sino-Indian border.[70]

-

Indian Army officers of the 4th Sikh Regiment captured a Police Station in Lahore, Pakistan, after winning the Battle of Burki, during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.

-

The Indian Air Force used 20 small and lightweight Canberra bombers against the Portuguese forces during Operation Vijay, which led to the Annexation of Goa.

-

Disputed areas in the western sector of the Sino-Indian border including Aksai Chin, 1988 CIA map

1960s after Nehruedit

Jawaharlal Nehru died on 27 May 1964, and Lal Bahadur Shastri succeeded him as prime minister. In 1965, India and Pakistan again went to war over Kashmir, but without any definitive outcome or alteration of the Kashmir boundary. The Tashkent Agreement was signed under the mediation of the Soviet government, but Shastri died on the night after the signing ceremony. A leadership election resulted in the elevation of Indira Gandhi, Nehru's daughter who had been serving as Minister for Information and Broadcasting, as the third prime minister. She defeated right-wing leader Morarji Desai. The Congress Party won a reduced majority in the 1967 elections owing to widespread disenchantment over rising prices of commodities, unemployment, economic stagnation, and food crisis. Indira Gandhi had started on a rocky note after agreeing to a devaluation of the rupee, which created much hardship for Indian businesses and consumers, and the import of wheat from the United States fell through due to political disputes.[71]

In 1967, India and China again engaged with each other in Sino-Indian War of 1967 after the PLA soldiers opened fire on the Indian soldiers who were making a fence on the border in Nathu La. The Indian forces successfully repelled Chinese forces and the outcome saw Chinese defeat with their withdrawal from Sikkim.

Morarji Desai entered Gandhi's government as deputy prime minister and finance minister, and with senior Congress politicians attempted to constrain Gandhi's authority. But following the counsel of her political advisor P. N. Haksar, Gandhi resuscitated her popular appeal by a major shift towards socialist policies. She successfully ended the Privy Purse guarantee for former Indian royalty, and waged a major offensive against party hierarchy over the nationalisation of India's banks. Although resisted by Desai and India's business community, the policy was popular with the masses. When Congress politicians attempted to oust Gandhi by suspending her Congress membership, Gandhi was empowered with a large exodus of members of parliament to her own Congress (R). The bastion of the Indian freedom struggle, the Indian National Congress, had split in 1969. Gandhi continued to govern with a slim majority.[72]

1970sedit

In 1971, Indira Gandhi and her Congress (R) were returned to power with a massively increased majority. The nationalisation of banks was carried out, and many other socialist economic and industrial policies enacted. India intervened in the Bangladesh War of Independence, a civil war taking place in Pakistan's Bengali half, after millions of refugees had fled the persecution of the Pakistani army. The clash resulted in the independence of East Pakistan, which became known as Bangladesh, and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's elevation to immense popularity. Relations with the United States grew strained, and India signed a 20-year treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union—breaking explicitly for the first time from non-alignment. In 1974, India tested its first nuclear weapon in the desert of Rajasthan, near Pokhran.

Merger of Sikkimedit

In 1973, anti-royalist riots took place in the Kingdom of Sikkim. In 1975, the Prime Minister of Sikkim appealed to the Indian Parliament for Sikkim to become a state of India. In April of that year, the Indian Army took over the city of Gangtok and disarmed the Chogyal's palace guards. Thereafter, a referendum was held in which 97.5 percent of voters supported abolishing the monarchy, effectively approving union with India.

India is said to have stationed 20,000–40,000 troops in a country of only 200,000 during the referendum.[73] On 16 May 1975, Sikkim became the 22nd state of the Indian Union, and the monarchy was abolished.[74] To enable the incorporation of the new state, the Indian Parliament amended the Indian Constitution. First, the 35th Amendment laid down a set of conditions that made Sikkim an "associate state", a special designation not used by any other state. A month later, the 36th Amendment repealed the 35th Amendment, and made Sikkim a full state, adding its name to the First Schedule of the Constitution.[75]

Formation of Northeastern statesedit

In the Northeast India, the state of Assam was divided into several states beginning in 1970 within the borders of what was then Assam. In 1963, the Naga Hills district became the 16th state of India under the name of Nagaland. Part of Tuensang was added to Nagaland. In 1970, in response to the demands of the Khasi, Jaintia and Garo people of the Meghalaya Plateau, the districts embracing the Khasi Hills, Jaintia Hills, and Garo Hills were formed into an autonomous state within Assam; in 1972 this became a separate state under the name of Meghalaya. In 1972, Arunachal Pradesh (the North-East Frontier Agency) and Mizoram (from the Mizo Hills in the south) were separated from Assam as union territories; both became states in 1986.[76]

-

Assam till the 1950s: The new states of Nagaland, Meghalaya and Mizoram formed in the 1960-70s. From Shillong, the capital of Assam was shifted to Dispur, now a part of Guwahati. After the Sino-Indian War in 1962, Arunachal Pradesh was also separated.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=History_of_India_(1947–present)

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk