A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| History of Lithuania |

|---|

|

| Chronology |

|

|

The history of Lithuania dates back to settlements founded about 10,000 years ago,[1][2] but the first written record of the name for the country dates back to 1009 AD.[3] Lithuanians, one of the Baltic peoples, later conquered neighboring lands and established the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 13th century (and also a short-lived Kingdom of Lithuania). The Grand Duchy was a successful and lasting warrior state. It remained fiercely independent and was one of the last areas of Europe to adopt Christianity (beginning in the 14th century). A formidable power, it became the largest state in Europe in the 15th century spread from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, through the conquest of large groups of East Slavs who resided in Ruthenia.[4] In 1385, the Grand Duchy formed a dynastic union with Poland through the Union of Krewo. Later, the Union of Lublin (1569) created the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. During the Second Northern War, the Grand Duchy sought protection under the Swedish Empire through the Union of Kėdainiai in 1655. However, it soon returned to being a part of the Polish–Lithuanian state, which persisted until 1795 when the last of the Partitions of Poland erased both independent Lithuania and Poland from the political map. After the dissolution, Lithuanians lived under the rule of the Russian Empire until the 20th century, although there were several major rebellions, especially in 1830–1831 and 1863.

On 16 February 1918, Lithuania was re-established as a democratic state. It remained independent until the onset of World War II, when it was occupied by the Soviet Union under the terms of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. Following a brief occupation by Nazi Germany after the Nazis waged war on the Soviet Union, Lithuania was again absorbed into the Soviet Union for nearly 50 years. In 1990–1991, Lithuania restored its sovereignty with the Act of the Re-Establishment of the State of Lithuania. Lithuania joined the NATO alliance in 2004 and the European Union as part of its enlargement in 2004.

Before statehood

Early settlement

The first humans arrived on the territory of modern Lithuania in the second half of the 10th millennium BC after the glaciers receded at the end of the last glacial period.[2] According to the historian Marija Gimbutas, these people came from two directions: the Jutland Peninsula and from present-day Poland. They brought two different cultures, as evidenced by the tools they used. They were traveling hunters and did not form stable settlements. In the 8th millennium BC, the climate became much warmer, and forests developed. The inhabitants of what is now Lithuania then traveled less and engaged in local hunting, gathering and fresh-water fishing. During the 6th–5th millennium BC, various animals were domesticated and dwellings became more sophisticated in order to shelter larger families. Agriculture did not emerge until the 3rd millennium BC due to a harsh climate and terrain and a lack of suitable tools to cultivate the land. Crafts and trade also started to form at this time.

Speakers of North-Western Indo-European might have arrived with the Corded Ware culture around 3200/3100 BC.[5]

Baltic tribes

The first Lithuanian people were a branch of an ancient group known as the Balts.[a] The main tribal divisions of the Balts were the West Baltic Old Prussians and Yotvingians, and the East Baltic Lithuanians and Latvians. The Balts spoke forms of the Indo-European languages.[7] Today, the only remaining Baltic nationalities are the Lithuanians and Latvians, but there were more Baltic groups or tribes in the past. Some of these merged into Lithuanians and Latvians (Samogitians, Selonians, Curonians, Semigallians), while others no longer existed after they were conquered and assimilated by the State of the Teutonic Order (Old Prussians, Yotvingians, Sambians, Skalvians, and Galindians).[8]

The Baltic tribes did not maintain close cultural or political contacts with the Roman Empire, but they did maintain trade contacts (see Amber Road). Tacitus, in his study Germania, described the Aesti people, inhabitants of the south-eastern Baltic Sea shores who were probably Balts, around the year 97 AD.[9] The Western Balts differentiated and became known to outside chroniclers first. Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD knew of the Galindians and Yotvingians, and early medieval chroniclers mentioned Prussians, Curonians and Semigallians.[10]

Lithuania, located along the lower and middle Neman River basin, comprised mainly the culturally different regions of Samogitia (known for its early medieval skeletal burials), and further east Aukštaitija, or Lithuania proper (known for its early medieval cremation burials).[11] The area was remote and unattractive to outsiders, including traders, which accounts for its separate linguistic, cultural and religious identity and delayed integration into general European patterns and trends.[7]

The Lithuanian language is considered to be very conservative for its close connection to Indo-European roots. It is believed to have differentiated from the Latvian language, the most closely related existing language, around the 7th century.[12] Traditional Lithuanian pagan customs and mythology, with many archaic elements, were long preserved. Rulers' bodies were cremated up until the Christianization of Lithuania: the descriptions of the cremation ceremonies of the grand dukes Algirdas and Kęstutis have survived.[13]

The Lithuanian tribe is thought to have developed more recognizably toward the end of the first millennium.[10] The first known reference to Lithuania as a nation ("Litua") comes from the Annals of the Quedlinburg monastery, dated 9 March 1009.[14] In 1009, the missionary Bruno of Querfurt arrived in Lithuania and baptized the Lithuanian ruler "King Nethimer."[15]

Formation of a Lithuanian state

From the 9th to the 11th centuries, coastal Balts were subjected to raids by the Vikings, and the kings of Denmark collected tribute at times. During the 10–11th centuries, Lithuanian territories were among the lands paying tribute to Kievan Rus', and Yaroslav the Wise was among the Ruthenian rulers who invaded Lithuania (from 1040). From the mid-12th century, it was the Lithuanians who were invading Ruthenian territories. In 1183, Polotsk and Pskov were ravaged, and even the distant and powerful Novgorod Republic was repeatedly threatened by the excursions from the emerging Lithuanian war machine toward the end of the 12th century.[16]

In the 12th century and afterwards, mutual raids involving Lithuanian and Polish forces took place sporadically, but the two countries were separated by the lands of the Yotvingians. The late 12th century brought an eastern expansion of German settlers (the Ostsiedlung) to the mouth of the Daugava River area. Military confrontations with Lithuanians followed at that time and at the turn of the century, but for the time being the Lithuanians had the upper hand.[17]

From the late 12th century, an organized Lithuanian military force existed; it was used for external raids, plundering and the gathering of slaves. Such military and pecuniary activities fostered social differentiation and triggered a struggle for power in Lithuania. This initiated the formation of early statehood, from which the Grand Duchy of Lithuania developed.[7] In 1231, the Danish Census Book mentions Baltic lands paying tribute to the Danes, including Lithuania (Littonia).[18]

Grand Duchy of Lithuania (13th century–1569)

13th–14th century Lithuanian state

Mindaugas and his kingdom

From the early 13th century, frequent foreign military excursions became possible due to the increased cooperation and coordination among the Baltic tribes.[7] Forty such expeditions took place between 1201 and 1236 against Ruthenia, Poland, Latvia and Estonia, which were then being conquered by the Livonian Order. Pskov was pillaged and burned in 1213.[17] In 1219, twenty-one Lithuanian chiefs signed a peace treaty with the state of Galicia–Volhynia. This event is widely accepted as the first proof that the Baltic tribes were uniting and consolidating.[19]

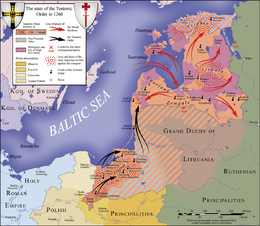

From the early 13th century, two German crusading military orders, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the Teutonic Knights, became established at the mouth of the Daugava River and in Chełmno Land respectively. Under the pretense of converting the population to Christianity, they proceeded to conquer much of the area that is now Latvia and Estonia, in addition to parts of Lithuania.[7] In response, a number of small Baltic tribal groups united under the rule of Mindaugas. Mindaugas, originally a kunigas or major chief, one of the five senior dukes listed in the treaty of 1219, is referred to as the ruler of all Lithuania as of 1236 in the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle.[20]

In 1236 the pope declared a crusade against the Lithuanians.[21] The Samogitians, led by Vykintas, Mindaugas' rival,[22] soundly defeated the Livonian Brothers and their allies in the Battle of Saule in 1236, which forced the Brothers to merge with the Teutonic Knights in 1237.[23] But Lithuania was trapped between the two branches of the Order.[21]

Around 1240, Mindaugas ruled over all of Aukštaitija. Afterwards, he conquered the Black Ruthenia region (which consisted of Grodno, Brest, Navahrudak and the surrounding territories).[7] Mindaugas was in process of extending his control to other areas, killing rivals or sending relatives and members of rival clans east to Ruthenia so they could conquer and settle there. They did that, but they also rebelled. The Ruthenian duke Daniel of Galicia sensed an occasion to recover Black Ruthenia and in 1249–1250 organized a powerful anti-Mindaugas (and "anti-pagan") coalition that included Mindaugas' rivals, Yotvingians, Samogitians and the Livonian Teutonic Knights. Mindaugas, however, took advantage of the divergent interests in the coalition he faced.[24]

In 1250, Mindaugas entered into an agreement with the Teutonic Order; he consented to receive baptism (the act took place in 1251) and relinquish his claim over some lands in western Lithuania, for which he was to receive a royal crown in return.[25] Mindaugas was then able to withstand a military assault from the remaining coalition in 1251, and, supported by the Knights, emerge as a victor to confirm his rule over Lithuania.[26]

On 17 July 1251, Pope Innocent IV signed two papal bulls that ordered the Bishop of Chełmno to crown Mindaugas as King of Lithuania, appoint a bishop for Lithuania, and build a cathedral.[27] In 1253, Mindaugas was crowned and a Kingdom of Lithuania was established for the first and only time in Lithuanian history.[28][29] Mindaugas "granted" parts of Yotvingia and Samogitia that he did not control to the Knights in 1253–1259. A peace with Daniel of Galicia in 1254 was cemented by a marriage deal involving Mindaugas' daughter and Daniel's son Shvarn. Mindaugas' nephew Tautvilas returned to his Duchy of Polotsk and Samogitia separated, soon to be ruled by another nephew, Treniota.[26]

In 1260, the Samogitians, victorious over the Teutonic Knights in the Battle of Durbe, agreed to submit themselves to Mindaugas' rule on the condition that he abandons the Christian religion; the king complied by terminating the emergent conversion of his country, renewed anti-Teutonic warfare (in the struggle for Samogitia)[30] and expanded further his Ruthenian holdings.[31] It is not clear whether this was accompanied by his personal apostasy.[7][30] Mindaugas thus established the basic tenets of medieval Lithuanian policy: defense against the German Order expansion from the west and north and conquest of Ruthenia in the south and east.[7]

Mindaugas was the principal founder of the Lithuanian state. He established for a while a Christian kingdom under the pope rather than the Holy Roman Empire, at a time when the remaining pagan peoples of Europe were no longer being converted peacefully, but conquered.[32]

Traidenis, Teutonic conquests of Baltic tribes

Mindaugas was murdered in 1263 by Daumantas of Pskov and Treniota, an event that resulted in great unrest and civil war. Treniota, who took over the rule of the Lithuanian territories, murdered Tautvilas, but was killed himself in 1264. The rule of Mindaugas' son Vaišvilkas followed. He was the first Lithuanian duke known to become an Orthodox Christian and settle in Ruthenia, establishing a pattern to be followed by many others.[30] Vaišvilkas was killed in 1267. A power struggle between Shvarn and Traidenis resulted; it ended in a victory for the latter. Traidenis' reign (1269–1282) was the longest and most stable during the period of unrest. Tradenis reunified all Lithuanian lands, repeatedly raided Ruthenia and Poland with success, defeated the Teutonic Knights in Prussia and in Livonia at the Battle of Aizkraukle in 1279. He also became the ruler of Yotvingia, Semigalia and eastern Prussia. Friendly relations with Poland followed, and in 1279, Tradenis' daughter Gaudemunda of Lithuania married Bolesław II of Masovia, a Piast duke.[7][31]

Pagan Lithuania was a target of northern Christian crusades of the Teutonic Knights and the Livonian Order.[33] In 1241, 1259 and 1275, Lithuania was also ravaged by raids from the Golden Horde, which earlier (1237–1240) debilitated Kievan Rus'.[31] After Traidenis' death, the German Knights finalized their conquests of Western Baltic tribes, and they could concentrate on Lithuania,[34] especially on Samogitia, to connect the two branches of the Order.[31] A particular opportunity opened in 1274 after the conclusion of the Great Prussian Rebellion and the conquest of the Old Prussian tribe. The Teutonic Knights then proceeded to conquer other Baltic tribes: the Nadruvians and Skalvians in 1274–1277 and the Yotvingians in 1283. The Livonian Order completed its conquest of Semigalia, the last Baltic ally of Lithuania, in 1291.[23]

Vytenis, Lithuania's great expansion under Gediminas

The family of Gediminas, whose members were about to form Lithuania's great native dynasty,[35] took over the rule of the Grand Duchy in 1285 under Butigeidis. Vytenis (r. 1295–1315) and Gediminas (r. 1315–1341), after whom the Gediminid dynasty is named, had to deal with constant raids and incursions from the Teutonic orders that were costly to repulse. Vytenis fought them effectively around 1298 and at about the same time was able to ally Lithuania with the German burghers of Riga. For their part, the Prussian Knights instigated a rebellion in Samogitia against the Lithuanian ruler in 1299–1300, followed by twenty incursions there in 1300–15.[31] Gediminas also fought the Teutonic Knights, and besides that made shrewd diplomatic moves by cooperating with the government of Riga in 1322–23 and taking advantage of the conflict between the Knights and Archbishop Friedrich von Pernstein of Riga.[36]

Gediminas expanded Lithuania's international connections by conducting correspondence with Pope John XXII as well as with rulers and other centers of power in Western Europe, and he invited German colonists to settle in Lithuania.[37] Responding to Gediminas' complaints about the aggression from the Teutonic Order, the pope forced the Knights to observe a four-year peace with Lithuania in 1324–1327.[36] Opportunities for the Christianization of Lithuania were investigated by the pope's legates, but they met with no success.[36] From the time of Mindaugas, the country's rulers attempted to break Lithuania's cultural isolation, join Western Christendom and thus be protected from the Knights, but the Knights and other interests had been able to block the process.[38] In the 14th century, Gediminas' attempts to become baptized (1323–1324) and establish Catholic Christianity in his country were thwarted by the Samogitians and Gediminas' Orthodox courtiers.[37] In 1325, Casimir, the son of the Polish king Władysław I, married Gediminas' daughter Aldona, who became queen of Poland when Casimir ascended the Polish throne in 1333. The marriage confirmed the prestige of the Lithuanian state under Gediminas, and a defensive alliance with Poland was concluded the same year. Yearly incursions of the Knights resumed in 1328–1340, to which the Lithuanians responded with raids into Prussia and Latvia.[7][36]

The reign of Grand Duke Gediminas constituted the first period in Lithuanian history in which the country was recognized as a great power, mainly due to the extent of its territorial expansion into Ruthenia.[7][39] Lithuania was unique in Europe as a pagan-ruled "kingdom" and fast-growing military power suspended between the worlds of Byzantine and Latin Christianity. To be able to afford the extremely costly defense against the Teutonic Knights, it had to expand to the east. Gediminas accomplished Lithuania's eastern expansion by challenging the Mongols, who from the 1230s sponsored a Mongol invasion of Rus'.[40] The collapse of the political structure of Kievan Rus' created a partial regional power vacuum that Lithuania was able to exploit.[38] Through alliances and conquest, in competition with the Principality of Moscow,[36] the Lithuanians eventually gained control of vast expanses of the western and southern portions of the former Kievan Rus'.[7][39] Gediminas' conquests included the western Smolensk region, southern Polesia and (temporarily) Kyiv, which was ruled around 1330 by Gediminas' brother Fiodor.[36] The Lithuanian-controlled area of Ruthenia grew to include most of modern Belarus and Ukraine (the Dnieper River basin) and comprised a massive state that stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea in the 14th and 15th centuries.[38][39]

In the 14th century, many Lithuanian princes installed to govern the Ruthenia lands accepted Eastern Christianity and assumed Ruthenian custom and names in order to appeal to the culture of their subjects. Through this means, integration into the Lithuanian state structure was accomplished without disturbing local ways of life.[7] The Ruthenian territories acquired were vastly larger, more densely populated and more highly developed in terms of church organization and literacy than the territories of core Lithuania. Thus the Lithuanian state was able to function because of the contributions of the Ruthenian culture representatives.[38] Historical territories of the former Ruthenian dukedoms were preserved under the Lithuanian rule, and the further they were from Vilnius, the more autonomous the localities tended to be.[41] Lithuanian soldiers and Ruthenians together defended Ruthenian strongholds, at times paying tribute to the Golden Horde for some of the outlying localities.[36] Ruthenian lands may have been ruled jointly by Lithuania and the Golden Horde as condominiums until the time of Vytautas, who stopped paying tribute.[42] Gediminas' state provided a counterbalance against the influence of Moscow and enjoyed good relations with the Ruthenian principalities of Pskov, Veliky Novgorod and Tver. Direct military confrontations with the Principality of Moscow under Ivan I occurred around 1335.[36]

Algirdas and Kęstutis

Around 1318, Gediminas' elder son Algirdas married Maria of Vitebsk, the daughter of Prince Yaroslav of Vitebsk, and settled in Vitebsk to rule the principality.[36] Of Gediminas' seven sons, four remained pagan and three converted to Orthodox Christianity.[7] Upon his death, Gediminas divided his domains among the seven sons, but Lithuania's precarious military situation, especially on the Teutonic frontier, forced the brothers to keep the country together.[43] From 1345, Algirdas took over as the Grand Duke of Lithuania. In practice, he ruled over Lithuanian Ruthenia only, whereas Lithuania proper was the domain of his equally able brother Kęstutis. Algirdas fought the Golden Horde Tatars and the Principality of Moscow; Kęstutis took upon himself the demanding struggle with the Teutonic Order.[7]

The warfare with the Teutonic Order continued from 1345, and in 1348, the Knights defeated the Lithuanians at the Battle of Strėva. Kęstutis requested King Casimir of Poland to mediate with the pope in hopes of converting Lithuania to Christianity, but the result was negative, and Poland took from Lithuania in 1349 the Halych area and some Ruthenian lands further north. Lithuania's situation improved from 1350, when Algirdas formed an alliance with the Principality of Tver. Halych was ceded by Lithuania, which brought peace with Poland in 1352. Secured by those alliances, Algirdas and Kęstutis embarked on the implementation of policies to expand Lithuania's territories further.[43]

Bryansk was taken in 1359, and in 1362, Algirdas captured Kyiv after defeating the Mongols at the Battle of Blue Waters.[39][40][43] Volhynia, Podolia and left-bank Ukraine were also incorporated. Kęstutis heroically fought for the survival of ethnic Lithuanians by attempting to repel about thirty incursions by the Teutonic Knights and their European guest fighters.[7] Kęstutis also attacked the Teutonic possessions in Prussia on numerous occasions, but the Knights took Kaunas in 1362.[44] The dispute with Poland renewed itself and was settled by the peace of 1366, when Lithuania gave up a part of Volhynia including Volodymyr. A peace with the Livonian Knights was also accomplished in 1367. In 1368, 1370 and 1372, Algirdas invaded the Grand Duchy of Moscow and each time approached Moscow itself. An "eternal" peace (the Treaty of Lyubutsk) was concluded after the last attempt, and it was much needed by Lithuania due to its involvement in heavy fighting with the Knights again in 1373–1377.[44]

The two brothers and Gediminas' other offspring left many ambitious sons with inherited territory. Their rivalry weakened the country in the face of the Teutonic expansion and the newly assertive Grand Duchy of Moscow, buoyed by the 1380 victory over the Golden Horde at the Battle of Kulikovo and intent on the unification of all Rus' lands under its rule.[7]

Jogaila's conflict with Kęstutis, Vytautas

Algirdas died in 1377, and his son Jogaila became grand duke while Kęstutis was still alive. The Teutonic pressure was at its peak, and Jogaila was inclined to cease defending Samogitia in order to concentrate on preserving the Ruthenian empire of Lithuania. The Knights exploited the differences between Jogaila and Kęstutis and procured a separate armistice with the older duke in 1379. Jogaila then made overtures to the Teutonic Order and concluded the secret Treaty of Dovydiškės with them in 1380, contrary to Kęstutis' principles and interests. Kęstutis felt he could no longer support his nephew and in 1381, when Jogaila's forces were preoccupied with quenching a rebellion in Polotsk, he entered Vilnius in order to remove Jogaila from the throne. A Lithuanian civil war ensued. Kęstutis' two raids against Teutonic possessions in 1382 brought back the tradition of his past exploits, but Jogaila retook Vilnius during his uncle's absence. Kęstutis was captured and died in Jogaila's custody. Kęstutis' son Vytautas escaped.[7][40][45]

Jogaila agreed to the Treaty of Dubysa with the Order in 1382, an indication of his weakness. A four-year truce stipulated Jogaila's conversion to Catholicism and the cession of half of Samogitia to the Teutonic Knights. Vytautas went to Prussia in seek of the support of the Knights for his claims, including the Duchy of Trakai, which he considered inherited from his father. Jogaila's refusal to submit to the demands of his cousin and the Knights resulted in their joint invasion of Lithuania in 1383. Vytautas, however, having failed to gain the entire duchy, established contacts with the grand duke. Upon receiving from him the areas of Grodno, Podlasie and Brest, Vytautas switched sides in 1384 and destroyed the border strongholds entrusted to him by the Order. In 1384, the two Lithuanian dukes, acting together, waged a successful expedition against the lands ruled by the Order.[7]

By that time, for the sake of its long-term survival, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had initiated the processes leading to its imminent acceptance of European Christendom.[7] The Teutonic Knights aimed at a territorial unification of their Prussian and Livonian branches by conquering Samogitia and all of Lithuania proper, following the earlier subordination of the Prussian and Latvian tribes. To dominate the neighboring Baltic and Slavic people and expand into a great Baltic power, the Knights used German and other volunteer fighters. They unleashed 96 onslaughts in Lithuania during the period 1345–1382, against which the Lithuanians were able to respond with only 42 retributive raids of their own. Lithuania's Ruthenian empire in the east was also threatened by both the unification of Rus' ambitions of Moscow and the centrifugal activities pursued by the rulers of some of the more distant provinces.[46]

13th–14th century Lithuanian society

The Lithuanian state of the later 14th century was primarily binational, Lithuanian and Ruthenian (in territories that correspond to the modern Belarus and Ukraine). Of its 800,000 square kilometers total area, 10% comprised ethnic Lithuania, probably populated by no more than 300,000 inhabitants. Lithuania was dependent for its survival on the human and material resources of the Ruthenian lands.[47]

The increasingly differentiated Lithuanian society was led by princes of the Gediminid and Rurik dynasties and the descendants of former kunigas chiefs from families such as the Giedraitis, Olshanski and Svirski. Below them in rank was the regular Lithuanian nobility (or boyars), in Lithuania proper strictly subjected to the princes and generally living on modest family farms, each tended by a few feudal subjects or, more often, slave workers if the boyar could afford them. For their military and administrative services, Lithuanian boyars were compensated by exemptions from public contributions, payments, and Ruthenian land grants. The majority of the ordinary rural workers were free. They were obligated to provide crafts and numerous contributions and services; for not paying these types of debts (or for other offences), one could be forced into slavery.[7][48]

The Ruthenian princes were Orthodox, and many Lithuanian princes also converted to Eastern Orthodoxy, even some who resided in Lithuania proper, or at least their wives. The masonry Ruthenian churches and monasteries housed learned monks, their writings (including Gospel translations such as the Ostromir Gospels) and collections of religious art. A Ruthenian quarter populated by Lithuania's Orthodox subjects, and containing their church, existed in Vilnius from the 14th century. The grand dukes' chancery in Vilnius was staffed by Orthodox churchmen, who, trained in the Church Slavonic language, developed Chancery Slavonic, a Ruthenian written language useful for official record keeping. The most important of the Grand Duchy's documents, the Lithuanian Metrica, the Lithuanian Chronicles and the Statutes of Lithuania, were all written in that language.[49]

German, Jewish and Armenian settlers were invited to live in Lithuania; the last two groups established their own denominational communities directly under the ruling dukes. The Tatars and Crimean Karaites were entrusted as soldiers for the dukes' personal guard.[49]

Towns developed to a much lesser degree than in nearby Prussia or Livonia. Outside of Ruthenia, the only cities were Vilnius (Gediminas' capital from 1323), the old capital of Trakai and Kaunas.[7][9][29] Kernavė and Kreva were the other old political centers.[36] Vilnius in the 14th century was a major social, cultural and trading center. It linked economically central and eastern Europe with the Baltic area. Vilnius merchants enjoyed privileges that allowed them to trade over most of the territories of the Lithuanian state. Of the passing Ruthenian, Polish and German merchants (many from Riga), many settled in Vilnius and some built masonry residencies. The city was ruled by a governor named by the grand duke and its system of fortifications included three castles. Foreign currencies and Lithuanian currency (from the 13th century) were widely used.[7][50]

The Lithuanian state maintained a patrimonial power structure. Gediminid rule was hereditary, but the ruler would choose the son he considered most able to be his successor. Councils existed, but could only advise the duke. The huge state was divided into a hierarchy of territorial units administered by designated officials who were also empowered in judicial and military matters.[7]

The Lithuanians spoke in a number of Aukštaitian and Samogitian (West-Baltic) dialects. But the tribal peculiarities were disappearing and the increasing use of the name Lietuva was a testimony to the developing Lithuanian sense of separate identity. The forming Lithuanian feudal system preserved many aspects of the earlier societal organization, such as the family clan structure, free peasantry and some slavery. The land belonged now to the ruler and the nobility. Patterns imported primarily from Ruthenia were used for the organization of the state and its structure of power.[51]

Following the establishment of Western Christianity at the end of the 14th century, the occurrence of pagan cremation burial ceremonies markedly decreased.[52]

Dynastic union with Poland, Christianization of the state

Jogaila's Catholic conversion and rule

As the power of the Lithuanian warlord dukes expanded to the south and east, the cultivated East Slavic Ruthenians exerted influence on the Lithuanian ruling class.[53] They brought with them the Church Slavonic liturgy of the Eastern Orthodox Christian religion, a written language (Chancery Slavonic) that was developed to serve the Lithuanian court's document-producing needs for a few centuries, and a system of laws. By these means, Ruthenians transformed Vilnius into a major center of Kievan Rus' civilization.[53] By the time of Jogaila's acceptance of Catholicism at the Union of Krewo in 1385, many institutions in his realm and members of his family had been to a large extent assimilated already into the Orthodox Christianity and became Russified (in part a result of the deliberate policy of the Gediminid ruling house).[53][54]

Catholic influence and contacts, including those derived from German settlers, traders and missionaries from Riga,[55] had been increasing for some time around the northwest region of the empire, known as Lithuania proper. The Franciscan and Dominican friar orders existed in Vilnius from the time of Gediminas. Kęstutis in 1349 and Algirdas in 1358 negotiated Christianization with the pope, the Holy Roman Empire and the Polish king. The Christianization of Lithuania thus involved both Catholic and Orthodox aspects. Conversion by force as practiced by the Teutonic Knights had actually been an impediment that delayed the progress of Western Christianity in the grand duchy.[7]

Jogaila, a grand duke since 1377, was himself still a pagan at the start of his reign. In 1386, agreed to the offer of the Polish crown by leading Polish nobles, who were eager to take advantage of Lithuania's expansion, if he become a Catholic and married the 13-year-old crowned king (not queen) Jadwiga.[56] For the near future, Poland gave Lithuania a valuable ally against increasing threats from the Teutonic Knights and the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Lithuania, in which Ruthenians outnumbered ethnic Lithuanians by several times, could ally with either the Grand Duchy of Moscow or Poland. A Russian deal was also negotiated with Dmitry Donskoy in 1383–1384, but Moscow was too distant to be able to assist with the problems posed by the Teutonic orders and presented a difficulty as a center competing for the loyalty of the Orthodox Lithuanian Ruthenians.[7][54]

Jogaila was baptized, given the baptismal name Władysław, married Queen Jadwiga, and was crowned King of Poland in February 1386.[57][58]

Jogaila's baptism and crowning were followed by the final and official Christianization of Lithuania.[59] In the fall of 1386, the king returned to Lithuania and the next spring and summer participated in mass conversion and baptism ceremonies for the general population.[60] The establishment of a bishopric in Vilnius in 1387 was accompanied by Jogaila's extraordinarily generous endowment of land and peasants to the Church and exemption from state obligations and control. This instantly transformed the Lithuanian Church into the most powerful institution in the country (and future grand dukes lavished even more wealth on it). Lithuanian boyars who accepted baptism were rewarded with a more limited privilege improving their legal rights.[61][62] Vilnius' townspeople were granted self-government. The Church proceeded with its civilizing mission of literacy and education, and the estates of the realm started to emerge with their own separate identities.[52]

Jogaila's orders for his court and followers to convert to Catholicism were meant to deprive the Teutonic Knights of the justification for their practice of forced conversion through military onslaughts. In 1403 the pope prohibited the Order from conducting warfare against Lithuania, and its threat to Lithuania's existence (which had endured for two centuries) was indeed neutralized. In the short term, Jogaila needed Polish support in his struggle with his cousin Vytautas.[52][54]

Lithuania at its peak under Vytautas

The Lithuanian Civil War of 1389–1392 involved the Teutonic Knights, the Poles, and the competing factions loyal to Jogaila and Vytautas in Lithuania. Amid ruthless warfare, the grand duchy was ravaged and threatened with collapse. Jogaila decided that the way out was to make amends and recognize the rights of Vytautas, whose original goal, now largely accomplished, was to recover the lands he considered his inheritance. After negotiations, Vytautas ended up gaining far more than that; from 1392 he became practically the ruler of Lithuania, a self-styled "Duke of Lithuania," under a compromise with Jogaila known as the Ostrów Agreement. Technically, he was merely Jogaila's regent with extended authority. Jogaila realized that cooperating with his able cousin was preferable to attempting to govern (and defend) Lithuania directly from Kraków.[62][63]

Vytautas had been frustrated by Jogaila's Polish arrangements and rejected the prospect of Lithuania's subordination to Poland.[64] Under Vytautas, a considerable centralization of the state took place, and the Catholicized Lithuanian nobility became increasingly prominent in state politics.[65] The centralization efforts began in 1393–1395, when Vytautas appropriated their provinces from several powerful regional dukes in Ruthenia.[66] Several invasions of Lithuania by the Teutonic Knights occurred between 1392 and 1394, but they were repelled with the help of Polish forces. Afterwards, the Knights abandoned their goal of conquest of Lithuania proper and concentrated on subjugating and keeping Samogitia. In 1395, Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia, the Order's formal superior, prohibited the Knights from raiding Lithuania.[67]

In 1395, Vytautas conquered Smolensk, and in 1397, he conducted a victorious expedition against a branch of the Golden Horde. Now he felt he could afford independence from Poland and in 1398 refused to pay the tribute due to Queen Jadwiga. Seeking freedom to pursue his internal and Ruthenian goals, Vytautas had to grant the Teutonic Order a large portion of Samogitia in the Treaty of Salynas of 1398. The conquest of Samogitia by the Teutonic Order greatly improved its military position as well as that of the associated Livonian Brothers of the Sword. Vytautas soon pursued attempts to retake the territory, an undertaking for which needed the help of the Polish king.[67][68]

During Vytautas' reign, Lithuania reached the peak of its territorial expansion, but his ambitious plans to subjugate all of Ruthenia were thwarted by his disastrous defeat in 1399 at the Battle of the Vorskla River, inflicted by the Golden Horde. Vytautas survived by fleeing the battlefield with a small unit and realized the necessity of a permanent alliance with Poland.[67][68]

The original Union of Krewo of 1385 was renewed and redefined on several occasions, but each time with little clarity due to the competing Polish and Lithuanian interests. Fresh arrangements were agreed to in the "unions" of Vilnius (1401), Horodło (1413), Grodno (1432) and Vilnius (1499).[69] In the Union of Vilnius, Jogaila granted Vytautas a lifetime rule over the grand duchy. In return, Jogaila preserved his formal supremacy, and Vytautas promised to "stand faithfully with the Crown and the King." Warfare with the Order resumed. In 1403, Pope Boniface IX banned the Knights from attacking Lithuania, but in the same year Lithuania had to agree to the Peace of Raciąż, which mandated the same conditions as in the Treaty of Salynas.[70]

Secure in the west, Vytautas turned his attention to the east once again. The campaigns fought between 1401 and 1408 involved Smolensk, Pskov, Moscow and Veliky Novgorod. Smolensk was retained, Pskov and Veliki Novgorod ended up as Lithuanian dependencies, and a lasting territorial division between the Grand Duchy and Moscow was agreed in 1408 in the treaty of Ugra, where a great battle failed to materialize.[70][71]

The decisive war with the Teutonic Knights (the Great War) was preceded in 1409 with a Samogitian uprising supported by Vytautas. Ultimately the Lithuanian–Polish alliance was able to defeat the Knights at the Battle of Grunwald on 15 July 1410, but the allied armies failed to take Marienburg, the Knights' fortress-capital. Nevertheless, the unprecedented total battlefield victory against the Knights permanently removed the threat that they had posed to Lithuania's existence for centuries. The Peace of Thorn (1411) allowed Lithuania to recover Samogotia, but only until the deaths of Jogaila and Vytautas, and the Knights had to pay a large monetary reparation.[72][73][74]

The Union of Horodło (1413) incorporated Lithuania into Poland again, but only as a formality. In practical terms, Lithuania became an equal partner with Poland, because each country was obliged to choose its future ruler only with the consent of the other, and the Union was declared to continue even under a new dynasty. Catholic Lithuanian boyars were to enjoy the same privileges as Polish nobles (szlachta). 47 top Lithuanian clans were colligated with 47 Polish noble families to initiate a future brotherhood and facilitate the expected full unity. Two administrative divisions (Vilnius and Trakai) were established in Lithuania, patterned after the existing Polish models.[75][76]

Vytautas practiced religious toleration and his grandiose plans also included attempts to influence the Eastern Orthodox Church, which he wanted to use as a tool to control Moscow and other parts of Ruthenia. In 1416, he elevated Gregory Tsamblak as his chosen Orthodox patriarch for all of Ruthenia (the established Orthodox Metropolitan bishop remained in Vilnius to the end of the 18th century).[66][77] These efforts were also intended to serve the goal of global unification of the Eastern and Western churches. Tsamblak led an Orthodox delegation to the Council of Constance in 1418.[78] The Orthodox synod, however, would not recognize Tsamblak.[77] The grand duke also established new Catholic bishoprics in Samogitia (1417)[78] and in Lithuanian Ruthenia (Lutsk and Kyiv).[77]

The Gollub War with the Teutonic Knights followed and in 1422, in the Treaty of Melno, the grand duchy permanently recovered Samogitia, which terminated its involvement in the wars with the Order.[79] Vytautas' shifting policies and reluctance to pursue the Order made the survival of German East Prussia possible for centuries to come.[80] Samogitia was the last region of Europe to be Christianized (from 1413).[78][81] Later, different foreign policies were prosecuted by Lithuania and Poland, accompanied by conflicts over Podolia and Volhynia, the grand duchy's territories in the southeast.[82]

Vytautas' greatest successes and recognition occurred at the end of his life, when the Crimean Khanate and the Volga Tatars came under his influence. Prince Vasily I of Moscow died in 1425, and Vytautas then administered the Grand Duchy of Moscow together with his daughter, Vasily's widow Sophia of Lithuania. In 1426–1428 Vytautas triumphantly toured the eastern reaches of his empire and collected huge tributes from the local princes.[80] Pskov and Veliki Novgorod were incorporated to the grand duchy in 1426 and 1428.[78] At the Congress of Lutsk in 1429, Vytautas negotiated the issue of his crowning as the King of Lithuania with Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund and Jogaila. That ambition was close to being fulfilled, but in the end was thwarted by last-minute intrigues and Vytautas' death. Vytautas' cult and legend originated during his later years and have continued until today.[80]

Around the first half of the 15th century

The dynastic link to Poland resulted in religious, political and cultural ties and increase of Western influence among the native Lithuanian nobility, and to a lesser extent among the Ruthenian boyars from the East, Lithuanian subjects.[64] Catholics were granted preferential treatment and access to offices because of the policies of Vytautas, officially pronounced in 1413 at the Union of Horodło, and even more so of his successors, aimed at asserting the rule of the Catholic Lithuanian elite over the Ruthenian territories.[65] Such policies increased the pressure on the nobility to convert to Catholicism. Ethnic Lithuania proper made up 10% of the area and 20% of the population of the Grand Duchy. Of the Ruthenian provinces, Volhynia was most closely integrated with Lithuania proper. Branches of the Gediminid family as well as other Lithuanian and Ruthenian magnate clans eventually became established there.[66]

During the period, a stratum of wealthy landowners, important also as a military force, was coming into being,[83] accompanied by the emerging class of feudal serfs assigned to them.[66] The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was for the time being largely preserved as a separate state with separate institutions, but efforts, originating mainly in Poland, were made to bring the Polish and Lithuanian elites and systems closer together.[75][76] Vilnius and other cities were granted the German system of laws (Magdeburg rights). Crafts and trade were developing quickly. Under Vytautas a network of chanceries functioned, first schools were established and annals written. Taking advantage of the historic opportunities, the great ruler opened Lithuania for the influence of the European culture and integrated his country with European Western Christianity.[78][83]

Under Jagiellonian rulers

The Jagiellonian dynasty founded by Jogaila (a member of one of the branches of the Gediminids) ruled Poland and Lithuania continuously between 1386 and 1572.

Following the deaths of Vytautas in 1430, another civil war ensued, and Lithuania was ruled by rival successors. Afterwards, the Lithuanian nobility on two occasions technically broke the union between Poland and Lithuania by selecting grand dukes unilaterally from the Jagiellonian dynasty. In 1440, the Lithuanian great lords elevated Casimir, Jogaila's second son, to the rule of the grand duchy. This issue was resolved by Casimir's election as king by the Poles in 1446. In 1492, Jogaila's grandson John Albert became the king of Poland, whereas his grandson Alexander became the grand duke of Lithuania. In 1501 Alexander succeeded John as king of Poland, which resolved the difficulty in the same manner as before.[68] A lasting connection between the two states was beneficial to Poles, Lithuanians, and Ruthenians, Catholic and Orthodox, as well as the Jagiellonian rulers themselves, whose hereditary succession rights in Lithuania practically guaranteed their election as kings in accordance with the customs surrounding the royal elections in Poland.[69]

On the Teutonic front, Poland continued its struggle, which in 1466 led to the Peace of Thorn and the recovery of much of the Piast dynasty territorial losses. A secular Duchy of Prussia was established in 1525. Its presence would greatly impact the futures of both Lithuania and Poland.[84]

The Tatar Crimean Khanate recognized the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire from 1475. Seeking slaves and booty, the Tatars raided vast portions of the grand duchy of Lithuania, burning Kyiv in 1482 and approaching Vilnius in 1505. Their activity resulted in Lithuania's loss of its distant territories on the Black Sea shores in the 1480s and 1490s. The last two Jagiellon kings were Sigismund I and Sigismund II Augustus, during whose reign the intensity of Tatar raids diminished due to the appearance of the military caste of Cossacks at the southeastern territories and the growing power of the Grand Duchy of Moscow.[85]

Lithuania needed a close alliance with Poland when, at the end of the 15th century, the increasingly assertive Grand Duchy of Moscow threatened some of Lithuania's Rus' principalities with the goal of "recovering" the formerly Orthodox-ruled lands. In 1492, Ivan III of Russia unleashed what turned out to be a series of Muscovite–Lithuanian Wars and Livonian Wars.[86]

In 1492, the border of Lithuania's loosely controlled eastern Ruthenian territory ran less than one hundred miles from Moscow. But as a result of the warfare, a third of the grand duchy's land area was ceded to the Russian state in 1503. Then the loss of Smolensk in July 1514 was particularly disastrous, even though it was followed by the successful Battle of Orsha in September, as the Polish interests were reluctantly recognizing the necessity of their own involvement in Lithuania's defense. The peace of 1537 left Gomel as the grand duchy's eastern edge.[86]

In the north, the Livonian War took place over the strategically and economically crucial region of Livonia, the traditional territory of the Livonian Order. The Livonian Confederation formed an alliance with the Polish-Lithuanian side in 1557 with the Treaty of Pozvol. Desired by both Lithuania and Poland, Livonia was then incorporated into the Polish Crown by Sigismund II. These developments caused Ivan the Terrible of Russia to launch attacks in Livonia beginning in 1558, and later on Lithuania. The grand duchy's fortress of Polotsk fell in 1563. This was followed by a Lithuanian victory at the Battle of Ula in 1564, but not a recovery of Polotsk. Russian, Swedish and Polish-Lithuanian occupations subdivided Livonia.[87]

Toward more integrated union

The Polish ruling establishment had been aiming at the incorporation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into Poland since before the Union of Krewo.[88] The Lithuanians were able to fend off this threat in the 14th and 15th centuries, but the dynamics of power changed in the 16th century. In 1508, the Polish Sejm voted funding for Lithuania's defense against Muscovy for the first time, and an army was fielded. The Polish nobility's executionist movement called for full incorporation of the Grand Duchy because of its increasing reliance on the support of the Polish Crown against Moscow's encroachments. This problem only grew more acute during the reign of Sigismund II Augustus, the last Jagiellonian king and grand duke of Lithuania, who had no heir who would inherit and continue the personal union between Poland and Lithuania. The preservation of the Polish-Lithuanian power arrangement appeared to require the monarch to force a decisive solution during his lifetime. The resistance to a closer and more permanent union was coming from Lithuania's ruling families, increasingly Polonized in cultural terms, but attached to the Lithuanian heritage and their patrimonial rule.[89][90]

Legal evolution had lately been taking place in Lithuania nevertheless. In the Privilege of Vilnius of 1563, Sigismund restored full political rights to the Grand Duchy's Orthodox boyars, which had been restricted up to that time by Vytautas and his successors; all members of the nobility were from then officially equal. Elective courts were established in 1565–66, and the Second Lithuanian Statute of 1566 created a hierarchy of local offices patterned on the Polish system. The Lithuanian legislative assembly assumed the same formal powers as the Polish Sejm.[89][90]

The Polish Sejm of January 1569, deliberating in Lublin, was attended by the Lithuanian lords at Sigismund's insistence. Most left town on 1 March, unhappy with the proposals of the Poles to establish rights to acquire property in Lithuania and other issues. Sigismund reacted by announcing the incorporation of the Grand Duchy's Volhynia and Podlasie voivodeships into the Polish Crown. Soon the large Kiev Voivodeship and Bratslav Voivodeship were also annexed. Ruthenian boyars in the formerly southeastern Grand Duchy mostly approved the territorial transfers, since it meant that they would become members of the privileged Polish nobility. But the king also pressured many obstinate deputies to agree on compromises important to the Lithuanian side. The arm twisting, combined with reciprocal guarantees for Lithuanian nobles' rights, resulted in the "voluntary" passage of the Union of Lublin on July 1. The combined polity would be ruled by a common Sejm, but the separate hierarchies of major state offices were to be retained. Many in the Lithuanian establishment found this objectionable, but in the end they were prudent to comply. For the time being, Sigismund managed to preserve the Polish-Lithuanian state as great power. Reforms necessary to protect its long-term success and survival were not undertaken.[89][90]

Lithuanian Renaissance

From the 16th to the mid-17th century, culture, arts, and education flourished in Lithuania, fueled by the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. The Lutheran ideas of the Reformation entered the Livonian Confederation by the 1520s, and Lutheranism soon became the prevailing religion in the urban areas of the region, while Lithuania remained Catholic.[91][92]

An influential book dealer was the humanist and bibliophile Francysk Skaryna (c. 1485—1540), who was the founding father of Belarusian letters. He wrote in his native Ruthenian (Chancery Slavonic) language,[93] as was typical for literati in the earlier phase of the Renaissance in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. After the middle of the 16th century, Polish predominated in literary productions.[94] Many educated Lithuanians came back from studies abroad to help build the active cultural life that distinguished 16th-century Lithuania, sometimes referred to as Lithuanian Renaissance (not to be confused with Lithuanian National Revival in the 19th century).

At this time, Italian architecture was introduced in Lithuanian cities, and Lithuanian literature written in Latin flourished. Also at this time, the first printed texts in the Lithuanian language emerged, and the formation of written Lithuanian language began. The process was led by Lithuanian scholars Abraomas Kulvietis, Stanislovas Rapalionis, Martynas Mažvydas and Mikalojus Daukša.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795)

New union with Poland

With the Union of Lublin of 1569, Poland and Lithuania formed a new state referred to as the Republic of Both Nations, but commonly known as Poland-Lithuania or the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Commonwealth, which officially consisted of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, was ruled by Polish and Lithuanian nobility, together with nobility-elected kings. The Union was designed to have a common foreign policy, customs and currency. Separate Polish and Lithuanian armies were retained, but parallel ministerial and central offices were established according to a practice developed by the Crown.[90] The Lithuanian Tribunal, a high court for the affairs of the nobility, was created in 1581.[95]

Following the death of Sigismund II Augustus in 1572, a joint Polish–Lithuanian monarch was to be elected as agreed in the Union of Lublin. According to the treaty, the title "Grand Duke of Lithuania" would be received by a jointly elected monarch in the Election sejm on his accession to the throne, thus losing its former institutional significance. However, the treaty guaranteed that the institution and the title "Grand Duke of Lithuania" will be preserved.[96][97]

On 20 April 1576 the congress of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania's nobles was held in Grodno which adopted an Universal. It was signed by the participating Lithuanian nobles who announced that if the delegates of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania will feel pressure from the Poles in the Election sejm, the Lithuanians will not be obliged by an oath of the Union of Lublin and will have the right to select a separate monarch.[98] On 29 May 1580 a ceremony was held in the Vilnius Cathedral during which bishop Merkelis Giedraitis presented Stephen Báthory (King of Poland since 1 May 1576) a luxuriously decorated sword and a cap adorned with pearls (both were sanctified by Pope Gregory XIII himself). Such ceremony manifested the sovereignty of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and had the meaning of elevation of the new Grand Duke of Lithuania, thus ignoring the stipulations of the Union of Lublin.[99][100]

Languages

The Lithuanian language fell into disuse in the circles of the grand ducal court in the second half of the 15th century in favor of Polish.[101] A century later, Polish was commonly used even by the ordinary Lithuanian nobility.[101] Following the Union of Lublin, Polonization increasingly affected all aspects of Lithuanian public life, but it took well over a century for the process to be completed. The 1588 Statutes of Lithuania were still written in the Ruthenian Chancery Slavonic language, just as earlier legal codifications were.[102] From about 1700, Polish was used in the Grand Duchy's official documents as a replacement for Ruthenian and Latin use.[103][104] The Lithuanian nobility became linguistically and culturally Polonized, while retaining a sense of Lithuanian identity.[105] The integrating process of the Commonwealth nobility was not regarded as Polonization in the sense of modern nationality, but rather as participation in the Sarmatism cultural-ideological current, erroneously understood to imply also a common (Sarmatian) ancestry of all members of the noble class.[104] The Lithuanian language survived, however, in spite of encroachments by the Ruthenian, Polish, Russian, Belarusian and German languages, as a peasant vernacular, and from 1547 in written religious use.[106]

Western Lithuania had an important role in the preservation of the Lithuanian language and its culture. In Samogitia, many nobles never ceased to speak Lithuanian natively. Northeastern East Prussia, sometimes referred to as Lithuania Minor, was populated mainly by Lithuanians[107] and predominantly Lutheran. The Lutherans promoted publishing of religious books in local languages, which is why the Catechism of Martynas Mažvydas was printed in 1547 in East Prussian Königsberg.[108]

Religion

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=History_of_LithuaniaText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk