A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

The area that is now Massachusetts was colonized by English settlers in the early 17th century and became the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the 18th century. Before that, it was inhabited by a variety of Native American tribes. Massachusetts is named after the Massachusett tribe that inhabited the area of present-day Greater Boston. The Pilgrim Fathers who sailed on the Mayflower established the first permanent settlement in 1620 at Plymouth Colony which set precedents but never grew large. A large-scale Puritan migration began in 1630 with the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and that spawned the settlement of other New England colonies.

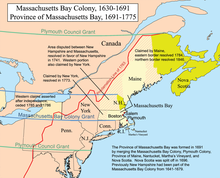

As the Colony grew, businessmen established wide-ranging trade, sending ships to the West Indies and Europe. Britain began to increase taxes on the New England colonies, and tensions grew with implementation of the Navigation Acts. These political and trade issues led to the revocation of the Massachusetts charter in 1684. The king established the Dominion of New England in 1686 to govern all of New England, and to centralize royal control and weaken local government. Sir Edmund Andros's intensely unpopular rule came to a sudden end in 1689 with an uprising sparked by the Glorious Revolution in England. The new king William III established the Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1691 to govern a territory roughly equivalent to the modern states of Massachusetts and Maine. Its governors were appointed by the crown, unlike the predecessor colonies that had elected their own governors. This increased friction between the colonists and the crown, which reached its height in the days leading up to the American Revolution in the 1760s and 1770s over the question of who could levy taxes. The American Revolutionary War began in Massachusetts in 1775 when London tried to shut down American self-government.

The commonwealth formally adopted the state constitution in 1780, electing John Hancock as its first governor. In the 19th century, New England became America's center of manufacturing with the development of precision manufacturing and weaponry in Springfield and Hartford, Connecticut, and large-scale textile mill complexes in Worcester, Haverhill, Lowell, and other communities throughout New England using their rivers for power. New England also was an intellectual center and center of abolitionism. The Springfield Armory made most of the weaponry for the Union in the American Civil War. After the war, immigrants from Europe, The Middle East and Asia flooded into Massachusetts, continuing to expand its industrial base until the 1950s when textiles and other industries started to fade away, leaving a "rust belt" of empty mills and factories. Labor unions were important after the 1860s, as was big-city politics. The state's strength as a center of education contributed to the development of an economy based on information technology and biotechnology in the later years of the 20th century, leading to the "Massachusetts Miracle" of the late 1980s.

Before European settlement

Massachusetts was originally inhabited by tribes of the Algonquian language family such as the Wampanoag, Narragansetts, Nipmucs, Pocomtucs, Mahicans, and Massachusetts.[1][2] The Vermont and New Hampshire borders and the Merrimack River valley was the traditional home of the Pennacook tribe. Cape Cod, Nantucket, Martha's Vineyard, and southeast Massachusetts were the home of the Wampanoags who established a close bond with the Pilgrim Fathers. The extreme end of the Cape was inhabited by the closely related Nauset tribe. Much of the central portion and the Connecticut River valley was home to the loosely organized Nipmucs. The Berkshires were the home of both the Pocomtuc and the Mahican tribes. Narragansetts from Rhode Island and Mahicans from Connecticut Colony were also present.

These tribes were generally dependent on hunting and fishing for most of their food supply.[1] Villages consisted of lodges called wigwams as well as long houses,[2] and tribes were led by male or female elders known as sachems.[3] Europeans began exploring the coast in the 16th century, but they made few attempts at permanent settlement anywhere. Early European explorers of the New England coast included Bartholomew Gosnold who named Cape Cod in 1602, Samuel de Champlain who charted the northern coast as far as Cape Cod in 1605 and 1606, John Smith, and Henry Hudson. Fishing ships from Europe also worked in the rich waters off the coast, and may have traded with some of the tribes. Large numbers of Indians were decimated by virgin soil epidemics, perhaps including smallpox, measles, influenza, or leptospirosis.[4] In 1617–1619, a disease killed 90 percent of the Indians in the region.[5]

Pilgrims and Puritans: 1620–1629

The first settlers in Massachusetts were the Pilgrims who established Plymouth Colony in 1620 and developed friendly relations with the Wampanoag people.[6] This was the second permanent English colony in America following Jamestown Colony. The Pilgrims had migrated from England to Holland to escape religious persecution for rejecting England's official church. They were allowed religious liberty in Holland, but they gradually became concerned that the next generation would lose their distinct English heritage. They approached the Virginia Company and asked to settle "as a distinct body of themselves"[citation needed] in America. In the fall of 1620, they sailed to America on the Mayflower, first landing near Provincetown at the tip of Cape Cod. The area did not lie within their charter, so the Pilgrims created the Mayflower Compact before landing, one of America's first documents of self-governance. The first year was extremely difficult, with inadequate supplies and very harsh weather, but Wampanoag sachem Massasoit and his people assisted them.

In 1621, the Pilgrims celebrated their first Thanksgiving Day together to thank God for the blessings of good harvest and survival. This Thanksgiving came to represent the peace that existed at that time between the Wampanoags and the Pilgrims, although only about half of the Mayflower company survived the first year. The colony grew slowly over the next ten years, and was estimated to have 300 inhabitants by 1630.[7]

A group of fur-trappers and traders established Wessagusset Colony near the Plymouth colony in Weymouth in 1622. They abandoned it in 1623, and it was replaced by another small colony led by Robert Gorges. This settlement also failed, and individuals from these colonies returned to England, joined the Plymouth colonists, or established individual outposts elsewhere on the shores of Massachusetts Bay. In 1624, the Dorchester Company established a settlement on Cape Ann. This colony only survived until 1626, although a few settlers remained.

Massachusetts Bay Colony: 1628–1686

The Pilgrims were followed by Puritans who established the Massachusetts Bay Colony at Salem (1629) and Boston (1630).[8] The Puritans strongly dissented from the theology and church polity of the Church of England, and they came to Massachusetts for religious freedom.[9] The Bay Colony was founded under a royal charter, unlike Plymouth Colony. The Puritan migration was mainly from East Anglia and southwestern regions of England, with an estimated 20,000 immigrants between 1628 and 1642. Massachusetts Bay colony quickly eclipsed Plymouth in population and economy, the chief factors being the large influx of population, more suitable harbor facilities for trade, and the growth of a prosperous merchant class.

Religious dissension and expansionism led to the founding of several new colonies shortly after Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay. Dissenters such as Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson were banished due to religious disagreements with Massachusetts Bay authorities. Williams established Providence Plantations in 1636. Over the next few years, another group, which included Hutchinson, established Newport and Portsmouth; these settlements eventually joined to form the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Others left Massachusetts Bay in order to establish other settlements, including Connecticut Colony on the Connecticut River and New Haven Colony on the coast.

In 1636, a group of settlers led by William Pynchon founded Springfield, Massachusetts (originally named Agawam), after scouting for the region's most advantageous location for trading and farming.[10][11] Springfield is located just north of the first of Connecticut River's unnavigable waterfalls, and it also sits amid the fertile valley which contains New England's best agricultural land. The Indian tribes surrounding Springfield were friendly, which was not always the case for the fledgling Connecticut colonies.[11][12] Pynchon annexed Springfield to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1640 rather than the much closer Connecticut Colony over tensions with Connecticut following the Pequot War.[13] Massachusetts Bay Colony's southern and western borders were thus established in 1640.[14]

King Philip's War (1675–76) was the bloodiest Indian war of the colonial period. In little over a year, Indians attacked nearly half of the region's towns, and they burned to the ground the major settlements at Providence and Springfield. New England's economy was all but ruined, and much of its population was killed.[15][16] Proportionately, it was one of the bloodiest and costliest wars in the history of North America.[17]

In 1645, the General Court ordered rural towns to increase sheep production. Sheep provided meat and especially wool for the local cloth industry, avoiding the expense of imports of British cloth.[18] In 1652, the General Court authorized Boston silversmith John Hull to produce local coinage in shilling, sixpence and threepence denominations to address a coin shortage in the colony.[19] To that point, the colony's economy had been entirely dependent on barter and foreign currency, including English, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese and counterfeit coins.[20]

Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660 and began to scrutinize the governmental oversight in the colonies, and Parliament passed the Navigation Acts to regulate trade for England's benefit. Massachusetts and Rhode Island had thriving merchant fleets, and they often ran afoul of the trade regulations. The English government also considered the Boston mint to be treasonous.[21] However, the colony ignored the English demands to cease mint operations until at least 1682.[22] King Charles formally vacated the Massachusetts charter in 1684.[23]

Dominion of New England: 1686–1692

In 1660, King Charles II was restored to the throne. Colonial matters brought to his attention led him to propose the amalgamation of all of the New England colonies into a single administrative unit. In 1685, he was succeeded by James II, an outspoken Catholic who implemented the proposal. In June 1684, the charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was annulled, but its government continued to rule until James appointed Joseph Dudley to the new post of President of New England in 1686. Dudley established his authority later in New Hampshire and the King's Province (part of current Rhode Island), maintaining this position until Sir Edmund Andros arrived to become the Royal Governor of the Dominion of New England. The rule of Andros was unpopular. He ruled without a representative assembly, vacated land titles, restricted town meetings, enforced the Navigation Acts, and promoted the Church of England, angering virtually every segment of Massachusetts colonial society. Andros dealt a major blow to the colonists by challenging their title to the land; unlike England the great majority of New Englanders were land-owners. Taylor says that because they "regarded secure real estate as fundamental to their liberty, status, and prosperity, the colonists felt horrified by the sweeping and expensive challenge to their land titles."[24]

After James II was overthrown by William III and Mary II in late 1688, Boston colonists overthrew Andros and his officials in 1689. Both Massachusetts and Plymouth returned to their previous governments until 1692. During King William's War (1689–1697), the colony launched an unsuccessful expedition against Quebec under Sir William Phips in 1690, which had been financed by issuing paper bonds set against the gains expected from taking the city.[25] The colony continued to be on the front lines of the war, and experienced widespread French and Indian raids on its northern and western frontiers.

Royal Province of Massachusetts Bay: 1692–1774

| Part of a series on |

| Reformed Christianity |

|---|

|

|

|

In 1691, William and Mary chartered the Province of Massachusetts Bay, combining the territories of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Maine, Nova Scotia (which then included New Brunswick), and the islands south of Cape Cod. For its first governor they chose Sir William Phips. Phips came to Boston in 1692 to begin his rule, and was immediately thrust into the witchcraft hysteria in Salem. He established the court that heard the notorious Salem witch trials, and oversaw the war effort until he was recalled in 1694.

Economy

The province was the largest and most economically important in New England, and one where many American institutions and traditions were formed. Unlike southern colonies, it was built around small towns rather than scattered farms. The westernmost portion of Massachusetts, the Berkshires, was settled during the three decades following the end of the French and Indian War, largely by Scots. Sir Francis Bernard, the Royal Governor, named this new area "Berkshire" after his home county in England. The largest settlement in Berkshire County was Pittsfield, Massachusetts, founded in 1761.[26]

The educational system, headed by Harvard College, was the best in the 13 colonies. Newspapers became a major communications system in the 18th century, with Boston taking a leading role in the British colonies.[27] Teenaged Benjamin Franklin (born January 17, 1706, in Milk Street) worked on one of the earliest newspapers, The New-England Courant (owned by his brother) until he ran away to Philadelphia in 1723. Five Boston newspapers presented a full range of opinions during the coming of the American revolution. In Worcester, printer Isaiah Thomas made the Massachusetts Spy the influential voice of the western settlers.[28]

Farming was the largest economic activity. Most farming towns were largely self-sufficient, with families trading with each other for items they did not produce themselves; the surplus was sold to cities.[29] and Fishing was important in coastal towns like Marblehead. Great quantities of cod were exported to the slave colonies in the West Indies.[30] Merchant trade was based in Salem and Boston, and numerous wealthy merchants traded internationally. They typically stationed their sons and nephews as agents in ports around the empire.[31] Their business grew dramatically after 1783 when they no longer were confined to the British Empire.[32] Shipbuilding was a fast-growing industry. Most other manufactured products were imported from Britain (or smuggled in from the Netherlands).

Banking

In 1690, the Massachusetts Bay Colony became the first to issue paper money in what would become the United States, but soon others began printing their own money as well. The demand for currency in the colonies was due to the scarcity of coins, which had been the primary means of trade.[33] Colonies' paper currencies were used to pay for their expenses and lend money to the colonies' citizens. Paper money quickly became the primary means of exchange within each colony, and it even began to be used in financial transactions with other colonies.[34] However, some of the currencies were not redeemable in gold or silver, which caused them to depreciate.[33] With the Currency Act of 1751, the British parliament limited the ability of the New England colonies to issue fiat paper currency. Under the 1751 act, the New England colonial governments could make paper money legal tender for the payment of public debts (such as taxes), and could issue bills of credit as a tool of government finance, but barred the use of paper money as legal tender for private debts.[35] Under continued pressure from the British merchant-creditors who disliked being paid in depreciated paper currency, the subsequent Currency Act of 1764 banned the issuance of bills of credit (paper money) throughout the colonies.[35][36] Colonial governments used workarounds to accept paper notes as payment for taxes and pressured Parliament to repeal the prohibition on paper money as legal tender for public debts, which Parliament ultimately did in 1773.[35]

The colony was always short of gold and silver and printed a great deal of paper money, which caused inflation that favored farmers but angered business interests. By 1750, however, the colony recalled its paper currency and transitioned to a specie currency based on the British reimbursement (in gold and silver) for its spending in the French and Indian wars. The large-scale merchants and Royal officials welcomed the transition but many farmers and smaller businessmen were opposed.[37]

Wars with France

The colony fought alongside British regulars in a series of French and Indian Wars characterized by brutal border raids and attacks by Indians organized and supplied by New France. Particularly in King William's War (1689–97) and Queen Anne's War (1702–13), the colony's rural communities were directly exposed to French and Indian attacks, with Deerfield raided in 1704 and Haverhill raided in 1708. Boston responded, launching naval expeditions against Acadia and Quebec in both wars.

During Queen Anne's War, Massachusetts men were involved in the Conquest of Acadia (1710), which became the Province of Nova Scotia. The province was also involved in Dummer's War, which drove Indian tribes from northern New England. In 1745, during King George's War, Massachusetts provincial forces successfully besieged Fortress Louisbourg. The fortress was returned to France at the end of the war, angering many colonists who viewed it as a threat to their security. During the French and Indian War, Governor William Shirley was instrumental in the Expulsion of the Acadians from Nova Scotia and trying to settle them in New England. After the expulsion, Shirley also was involved in transporting New England Planters to settle Nova Scotia on the former Acadian farms.[38] Many troops from Massachusetts participated in the successful Siege of Havana in 1762. Britain's victory in the war led to its acquisition of New France, removing the immediate northern threat to Massachusetts that the French had posed.

Disasters

Boston was hit by a major smallpox epidemic in 1721. Some colonial leaders called for use of the new technique of inoculation, whereby a patient would get a weak form of the disease and become permanently immune. Puritan minister Cotton Mather and physician Zabdiel Boylston led the drive for inoculation, while physician William Douglass and newspaper editor James Franklin led the opposition.[39]

In 1755, about 4:15 am on Tuesday, November 18, was the most destructive earthquake yet known in New England. The first pulsations of the ground were followed for about a minute of tremulous motion. Next came a quick vibration and several jerks much worse than the first. Houses rocked and cracked; furniture fell over. Dr. Edward A. Holyoke, of Salem, wrote in his diary that he "thought of nothing less than being buried instantly in the ruins of the house." The shaking continued for two to three minutes more, and seemed to move from northwest to southeast. The ocean along the coast was affected; ships shook so much that sleeping sailors awoke, thinking they had run aground. In Boston, the earthquake threw dishes on the floor, stopped clocks, and bent vane-rods on churches and Faneuil Hall. Stone walls collapsed. New springs appeared, and old springs dried up. Subterranean streams changed their courses, emptying many wells. The worst damage was to chimneys. In Boston alone, about a hundred were leveled; about fifteen hundred were damaged, the streets in some places almost covered with fallen bricks. Falling chimneys broke some roofs. Many wooden buildings in Boston were thrown down, and some brick buildings suffered; the gable ends of twelve or fifteen were knocked down to the eaves. Despite the danger and many narrow escapes, no one was killed or seriously injured. Aftershocks continued for four days.[40][41]

Politics

The relationship between the provincial government and the crown-appointed governor was often difficult and contentious. The governors sought to assert the royal prerogatives granted in the provincial charter, and the provincial government sought to strip or minimize the governor's power. For example, each governor was ordered to enact legislation for providing permanent salaries for crown officials, but the legislature refused to do so, using its ability to grant stipends annually as a means of control over the governor. The province's periodic issuance of paper currency was also a persistent source of friction between factions in the province, due to its inflationary effects. Notable royal governors during this period were Joseph Dudley, Thomas Hutchinson, Jonathan Belcher, Francis Bernard, and General Thomas Gage. Gage was the last British governor of Massachusetts, and his effective rule extended to little more than Boston.

Revolutionary Massachusetts: 1760s–1780s

Massachusetts was a center of the movement for independence from Great Britain, earning it the nickname, the "Cradle of Liberty". Colonists here had long had uneasy relations with the British monarchy, including open rebellion under the Dominion of New England in the 1680s.[42] The Boston Tea Party is an example of the protest spirit in the early 1770s, while the Boston Massacre escalated the conflict.[43] Anti-British activity by men like Sam Adams and John Hancock, followed by reprisals by the British government, were a primary reason for the unity of the Thirteen Colonies and the outbreak of the American Revolution.[44] The Battles of Lexington and Concord initiated the American Revolutionary War and were fought in the Massachusetts towns of Lexington and Concord.[45] Future President George Washington took over what would become the Continental Army after the battle. His first victory was the Siege of Boston in the winter of 1775–76, after which the British were forced to evacuate the city.[46] The event is still celebrated in Suffolk County as Evacuation Day.[47] In 1777, George Washington and Henry Knox founded the Arsenal at Springfield, which catalyzed many innovations in Massachusetts' Connecticut River Valley.

Boston Massacre

Boston was the center of revolutionary activity in the decade before 1775, with Massachusetts natives Samuel Adams, John Adams, and John Hancock as leaders who would become important in the revolution. Boston had been under military occupation since 1768. When customs officials were attacked by mobs, two regiments of British regulars arrived. They had been housed in the city with increasing public outrage.

In Boston on March 5, 1770, what began as a rock-throwing incident against a few British soldiers ended in the shooting of five men by British soldiers in what became known as the Boston Massacre. The incident caused further anger against British authority in the commonwealth over taxes and the presence of the British soldiers.

Boston Tea Party

One of the many taxes protested by the colonists was a tax on tea, imposed when Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, and retained when most of the provisions of those acts were repealed. With the passage of the Tea Act in 1773, tea sold by the British East India Company would become less expensive than smuggled tea, and there would be reduced profit-making opportunities for Massachusetts merchants traded in tea. This led to protests against the delivery of the company's tea to Boston. On December 16, 1773, when a tea ship of the East India Company was planning to land taxed tea in Boston, a group of local men known as the Sons of Liberty sneaked onto the boat the night before it was to be unloaded and dumped all the tea into the harbor, an act known as the Boston Tea Party.

American Revolution

The Boston Tea Party prompted the British government to pass the Intolerable Acts in 1774 that brought stiff punishment on Massachusetts. They closed the port of Boston, the economic lifeblood of the Commonwealth, and reduced self-government. Local self-government was ended and the colony put under military rule. The Patriots formed the Massachusetts Provincial Congress after the provincial legislature was disbanded by Governor Gage. The suffering of Boston and the tyranny of its rule caused great sympathy and stirred resentment throughout the Thirteen Colonies. On February 9, 1775, the British Parliament declared Massachusetts to be in rebellion, and sent additional troops to restore order to the colony. With the local population largely opposing British authority, troops moved from Boston on April 18, 1775, to destroy the military supplies of local resisters in Concord. Paul Revere made his famous ride to warn the locals in response to this march. On the 19th, in the Battles of Lexington and Concord, where the famous "shot heard 'round the world" was fired, British troops, after running over the Lexington militia, were forced back into the city by local resistors. The city was quickly brought under siege. Fighting broke out again in June when the British took the Charlestown Peninsula in the Battle of Bunker Hill after the colonial militia fortified Breed's Hill. The British won the battle, but at a very large cost, and were unable to break the siege. The British made a desperate attempt by using biological weapons against the Americans by sending infected civilians with smallpox behind American lines but this was soon contained by Continental General George Washington who launched a vaccination program to ensure his troops and civilians were in good health after the damage biological warfare caused. Soon after the Battle of Bunker Hill, General George Washington took charge of the rebel army, and when he acquired heavy cannon in March 1776, the British were forced to leave, marking the first great colonial victory of the war. Ever since, "Evacuation Day" has been celebrated as a state holiday.

Massachusetts was not invaded again but in 1779 the disastrous Penobscot Expedition took place in the District of Maine, then part of the Commonwealth. Trapped by the British fleet, the American sailors sank the ships of the Massachusetts state navy before it could be captured by the British. In May 1778, the section of Freetown that later became Fall River was raided by the British, and in September 1778, the communities of Martha's Vineyard and New Bedford were also subjected to a British raid.

John Adams was a leader in the independence movement and he helped secure a unanimous vote for independence and on July 4, 1776, the United States Declaration of Independence was adopted in Philadelphia. It was signed first by Massachusetts resident John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress. Soon afterward the Declaration of Independence was read to the people of Boston from the balcony of the State House. Massachusetts was no longer a colony; it was a state and part of a new nation, the United States of America.

Federalist Era: 1780–1815

A Constitutional Convention drew up a state constitution, which was drafted primarily by John Adams, and ratified by the people on June 15, 1780. Adams, along with Samuel Adams and James Bowdoin, wrote in the Preamble to the Constitution of the Commonwealth:

We, therefore, the people of Massachusetts, acknowledging, with grateful hearts, the goodness of the Great Legislator of the Universe, in affording us, in the course of His Providence, an opportunity, deliberately and peaceably, without fraud, violence or surprise, on entering into an Original, explicit, and Solemn Compact with each other; and of forming a new Constitution of Civil Government, for Ourselves and Posterity, and devoutly imploring His direction in so interesting a design, Do agree upon, ordain and establish, the following Declaration of Rights, and Frame of Government, as the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Bostonian John Adams, known as the "Atlas of Independence", was an important figure in both the struggle for independence as well as the formation of the new United States.[48] Adams was highly involved in the push for separation from Britain and the writing of the Massachusetts Constitution in 1780 (which, in the Elizabeth Freeman and Quock Walker cases, effectively made Massachusetts the first state to have a constitution that declared universal rights and, as interpreted by Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice William Cushing, abolished slavery).[48][49] Adams became minister to Britain in the 1780s, Vice President in 1789 and succeeded Washington as President in 1797. His son, John Quincy Adams, would go on to become the sixth US president.

The new constitution

Massachusetts was the first state in the United States to abolish slavery. (Vermont, which became part of the U.S. in 1791, abolished adult slavery somewhat earlier than Massachusetts, in 1777.) The new constitution also dropped any religious tests for political office, though local tax money had to be paid to support local churches. People who belonged to non-Congregational churches paid their tax money to their own church, and the churchless paid to the Congregationalists. Baptist leader Isaac Backus vigorously fought these provisions, arguing people should have freedom of choice regarding financial support of religion. Adams drafted most of the document and despite numerous amendments it still follows his line of thought. He distrusted utopians and pure democracy, and put his faith in a system of checks and balances; he admired the principles of the unwritten British Constitution. He insisted on a bicameral legislature which would represent both the gentlemen and the common citizen. Above all he insisted on a government by laws, not men.[50] The constitution also changed the name of the Massachusetts Bay State to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Still in force, it is the oldest constitution in current use in the world.

Shays' Rebellion

The economy of rural Massachusetts suffered an economic depression after the war ended. Merchants, pressured for hard currency by overseas partners, made similar demands on local debtors, and the state raised taxes in order to pay off its own war debts. Efforts to collect both public and private debts from cash-poor farmers led to protests that flared into direct action in August 1786. Rebels calling themselves Regulators (after the North Carolina Regulator movement of the 1760s) succeeded in shutting down courts meeting to hear debt and tax collection cases. By the end of 1786 a farmer in western Massachusetts named Daniel Shays emerged as one of the ringleaders, and government attempts to squelch the protests only served to radicalize the protestors. In January 1787 Shays and Luke Day organized an attempt to take the federal Springfield Armory; state militia holding the armory beat back the attempt with cannon fire. A private militia raised by wealthy Boston merchants and led by General Benjamin Lincoln broke the back of the rebellion in early February at Petersham, but small-scale resistance continued in the western parts of the state for a while.[51]

The state put down the rebellion—but if it had been too weak to do so it would be no help to call on the ineffective federal government. The event led nationalists like George Washington to redouble efforts to strengthen the weak national government as necessary for survival in a dangerous world. Massachusetts, divided along class lines polarized by the rebellion, only narrowly ratified the United States Constitution in 1788.[52]

Johnny Appleseed

John Chapman often called Johnny "Appleseed" (born September 26, 1774, in Leominster, Massachusetts) was an American folk hero and pioneer nurseryman who introduced apple trees and established orchards to many areas in the Midwestern region of the country including Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana. Today, Appleseed is the official folk hero of Massachusetts and his stature has served a focus in many children's books, movies, and folk tales since the end of the Civil War.[53]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=History_of_Massachusetts

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk