A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series of overviews on |

| Marine life |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Plankton |

|---|

|

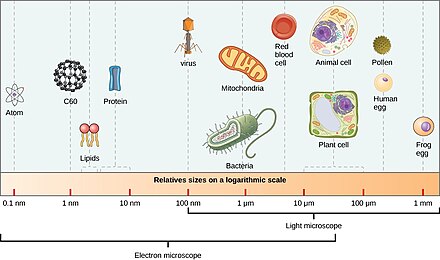

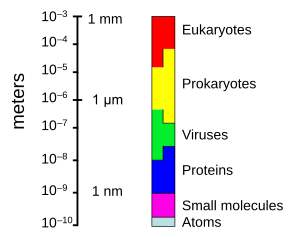

Marine microorganisms are defined by their habitat as microorganisms living in a marine environment, that is, in the saltwater of a sea or ocean or the brackish water of a coastal estuary. A microorganism (or microbe) is any microscopic living organism or virus, which is invisibly small to the unaided human eye without magnification. Microorganisms are very diverse. They can be single-celled[1] or multicellular and include bacteria, archaea, viruses, and most protozoa, as well as some fungi, algae, and animals, such as rotifers and copepods. Many macroscopic animals and plants have microscopic juvenile stages. Some microbiologists also classify viruses as microorganisms, but others consider these as non-living.[2][3]

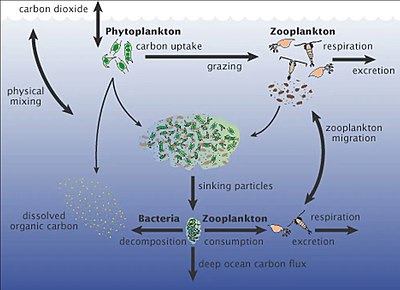

Marine microorganisms have been variously estimated to make up about 70%,[4] or about 90%,[5][6] of the biomass in the ocean. Taken together they form the marine microbiome. Over billions of years this microbiome has evolved many life styles and adaptations and come to participate in the global cycling of almost all chemical elements.[7] Microorganisms are crucial to nutrient recycling in ecosystems as they act as decomposers. They are also responsible for nearly all photosynthesis that occurs in the ocean, as well as the cycling of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and other nutrients and trace elements.[8] Marine microorganisms sequester large amounts of carbon and produce much of the world's oxygen.

A small proportion of marine microorganisms are pathogenic, causing disease and even death in marine plants and animals.[9] However marine microorganisms recycle the major chemical elements, both producing and consuming about half of all organic matter generated on the planet every year. As inhabitants of the largest environment on Earth, microbial marine systems drive changes in every global system.

In July 2016, scientists reported identifying a set of 355 genes from the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all life on the planet, including the marine microorganisms.[10] Despite its diversity, microscopic life in the oceans is still poorly understood. For example, the role of viruses in marine ecosystems has barely been explored even in the beginning of the 21st century.[11]

Overview

Microorganisms make up about 70% of the marine biomass.[4] A microorganism, or microbe, is a microscopic organism too small to be recognised adequately with the naked eye. In practice, that includes organisms smaller than about 0.1 mm.[12]: 13

Such organisms can be single-celled[1] or multicellular. Microorganisms are diverse and include all bacteria and archaea, most protists including algae, protozoa and fungal-like protists, as well as certain microscopic animals such as rotifers. Many macroscopic animals and plants have microscopic juvenile stages. Some microbiologists also classify viruses as microorganisms, but others consider these as non-living.[2][3]

Microorganisms are crucial to nutrient recycling in ecosystems as they act as decomposers. Some microorganisms are pathogenic, causing disease and even death in plants and animals.[9] As inhabitants of the largest environment on Earth, microbial marine systems drive changes in every global system. Microbes are responsible for virtually all the photosynthesis that occurs in the ocean, as well as the cycling of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and other nutrients and trace elements.[8]

| Marine microorganisms | |

While recent technological developments and scientific discoveries have been substantial, we still lack a major understanding at all levels of the basic ecological questions in relation to the microorganisms in our seas and oceans. These fundamental questions are:

1. What is out there? Which microorganisms are present in our seas and oceans and in what numbers do they occur?

2. What are they doing? What functions do each of these microorganisms perform in the marine environment and how do they contribute to the global cycles of energy and matter?

3. What are the factors that determine the presence or absence of a microorganism and how do they influence biodiversity and function and vice versa?

– European Science Foundation, 2012[12]: 14

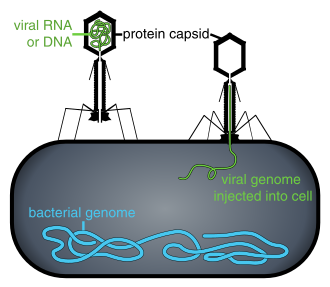

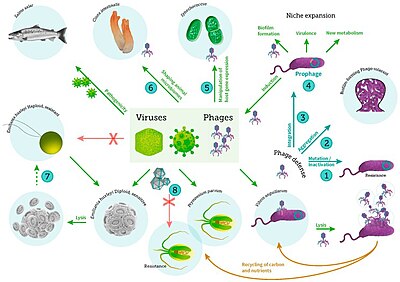

Microscopic life undersea is diverse and still poorly understood, such as for the role of viruses in marine ecosystems.[13] Most marine viruses are bacteriophages, which are harmless to plants and animals, but are essential to the regulation of saltwater and freshwater ecosystems.[14] They infect and destroy bacteria in aquatic microbial communities, and are the most important mechanism of recycling carbon in the marine environment. The organic molecules released from the dead bacterial cells stimulate fresh bacterial and algal growth.[15] Viral activity may also contribute to the biological pump, the process whereby carbon is sequestered in the deep ocean.[16]

A stream of airborne microorganisms circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes.[17] Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in sea spray. In 2018, scientists reported that hundreds of millions of viruses and tens of millions of bacteria are deposited daily on every square meter around the planet.[18][19]

Microscopic organisms live throughout the biosphere. The mass of prokaryote microorganisms — which includes bacteria and archaea, but not the nucleated eukaryote microorganisms — may be as much as 0.8 trillion tons of carbon (of the total biosphere mass, estimated at between 1 and 4 trillion tons).[20] Single-celled barophilic marine microbes have been found at a depth of 10,900 m (35,800 ft) in the Mariana Trench, the deepest spot in the Earth's oceans.[21][22] Microorganisms live inside rocks 580 m (1,900 ft) below the sea floor under 2,590 m (8,500 ft) of ocean off the coast of the northwestern United States,[21][23] as well as 2,400 m (7,900 ft; 1.5 mi) beneath the seabed off Japan.[24] The greatest known temperature at which microbial life can exist is 122 °C (252 °F) (Methanopyrus kandleri).[25] In 2014, scientists confirmed the existence of microorganisms living 800 m (2,600 ft) below the ice of Antarctica.[26][27] According to one researcher, "You can find microbes everywhere — they're extremely adaptable to conditions, and survive wherever they are."[21] Marine microorganisms serve as "the foundation of all marine food webs, recycling major elements and producing and consuming about half the organic matter generated on Earth each year".[28][29]

Marine viruses

including viral infection of bacteria, phytoplankton and fish[30]

A virus is a small infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of other organisms. Viruses can infect all types of life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.[31]

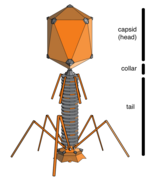

When not inside an infected cell or in the process of infecting a cell, viruses exist in the form of independent particles. These viral particles, also known as virions, consist of two or three parts: (i) the genetic material (genome) made from either DNA or RNA, long molecules that carry genetic information; (ii) a protein coat called the capsid, which surrounds and protects the genetic material; and in some cases (iii) an envelope of lipids that surrounds the protein coat when they are outside a cell. The shapes of these virus particles range from simple helical and icosahedral forms for some virus species to more complex structures for others. Most virus species have virions that are too small to be seen with an optical microscope. The average virion is about one one-hundredth the size of the average bacterium.

The origins of viruses in the evolutionary history of life are unclear: some may have evolved from plasmids—pieces of DNA that can move between cells—while others may have evolved from bacteria. In evolution, viruses are an important means of horizontal gene transfer, which increases genetic diversity.[32] Viruses are considered by some to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce, and evolve through natural selection. However, they lack key characteristics (such as cell structure) that are generally considered necessary to count as life. Because they possess some but not all such qualities, viruses have been described as "organisms at the edge of life"[33] and as replicators.[34]

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk