A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Paul VI | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

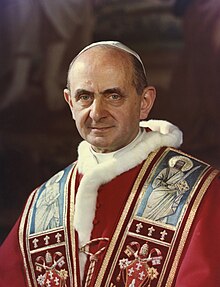

Official portrait, 1969 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Church | Catholic Church | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Papacy began | 21 June 1963 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Papacy ended | 6 August 1978 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | John XXIII | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | John Paul I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ordination | 29 May 1920 by Giacinto Gaggia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consecration | 12 December 1954 by Eugène Tisserant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Created cardinal | 15 December 1958 by John XXIII | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini 26 September 1897 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 6 August 1978 (aged 80) Castel Gandolfo, Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Previous post(s) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | University of Milan (JCD) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coat of arms |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sainthood | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feast day |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Venerated in |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beatified | 19 October 2014 Saint Peter's Square, Vatican City by Pope Francis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canonized | 14 October 2018 Saint Peter's Square, Vatican City by Pope Francis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Attributes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Patronage |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shrines | None | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ordination history | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other popes named Paul | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pope Paul VI (Latin: Paulus VI; Italian: Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, Italian: [dʒoˈvanni batˈtista enˈriːko anˈtɔːnjo maˈriːa monˈtiːni]; 26 September 1897 – 6 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his death in August 1978. Succeeding John XXIII, he continued the Second Vatican Council, which he closed in 1965, implementing its numerous reforms. He fostered improved ecumenical relations with Eastern Orthodox and Protestant churches, which resulted in many historic meetings and agreements. In January 1964, he flew to Jordan, the first time a reigning pontiff had left Italy in more than a century.[9]

Montini served in the Holy See's Secretariat of State from 1922 to 1954, and along with Domenico Tardini was considered the closest and most influential advisor of Pope Pius XII. In 1954, Pius named Montini Archbishop of Milan, the largest Italian diocese. Montini later became the Secretary of the Italian Bishops' Conference. John XXIII elevated Montini to the College of Cardinals in 1958, and after his death, Montini was, with little opposition, elected his successor, taking the name Paul VI.[10]

He re-convened the Second Vatican Council, which had been suspended during the interregnum. After its conclusion, Paul VI took charge of the interpretation and implementation of its mandates, finely balancing the conflicting expectations of various Catholic groups. The resulting reforms were among the widest and deepest in the Chuch's history.

Paul VI spoke repeatedly to Marian conventions and Mariological meetings, visited Marian shrines and issued three Marian encyclicals. Following Ambrose of Milan, he named Mary as the Mother of the Church during the Second Vatican Council.[11] He described himself as a humble servant of a suffering humanity and demanded significant changes from the rich in North America and Europe in favour of the poor in the Third World.[12] His opposition to birth control in the 1968 encyclical Humanae vitae was strongly contested, especially in Western Europe and North America. The same opposition emerged in reaction to some of his political doctrines.

Pope Benedict XVI, citing his heroic virtue, proclaimed him venerable on 20 December 2012. Pope Francis beatified Paul VI on 19 October 2014, after the recognition of a miracle attributed to his intercession. His liturgical feast was celebrated on the date of his birth, 26 September, until 2019 when it was changed to the date of his priestly ordination, 29 May.[1] Pope Francis canonised him on 14 October 2018.

Early life

Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini was born in the village of Concesio, in the Province of Brescia, Lombardy, Italy, in 1897. His father, Giorgio Montini (1860–1943), was a lawyer, journalist, director of the Catholic Action, and member of the Italian Parliament. His mother, Giudetta Alghisi (1874–1943), was from a family of rural nobility. He had two brothers, Francesco Montini (1900–1971), who became a physician, and Lodovico Montini (1896–1990), who became a lawyer and politician.[13][14] On 30 September 1897, he was baptised with the name Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini.[15] He attended the Cesare Arici school, run by the Jesuits, and in 1916 received a diploma from the Arnaldo da Brescia public school in Brescia. His education was often interrupted by bouts of illness.

In 1916, he entered the seminary to become a Catholic priest. He was ordained on 29 May 1920 in Brescia and celebrated his first Mass at the Santa Maria delle Grazie, Brescia.[16] Montini concluded his studies in Milan with a doctorate in canon law in the same year.[17] He later studied at the Gregorian University, the University of Rome La Sapienza and, at the request of Giuseppe Pizzardo, the Pontifical Academy of Ecclesiastical Nobles. In 1922, at the age of twenty-five, again at the request of Giuseppe Pizzardo, Montini entered the Secretariat of State, where he worked under Pizzardo together with Francesco Borgongini-Duca, Alfredo Ottaviani, Carlo Grano, Domenico Tardini and Francis Spellman.[18] Consequently, he never had an appointment as a parish priest. In 1925 he helped found the publishing house Morcelliana in Brescia, focused on promoting a 'Christian-inspired culture'.[19]

Vatican career

Diplomatic service

Montini had just one foreign posting in the diplomatic service of the Holy See as Secretary in the office of the papal nuncio to Poland in 1923. Of the nationalism he experienced there he wrote: "This form of nationalism treats foreigners as enemies, especially foreigners with whom one has common frontiers. Then one seeks the expansion of one's own country at the expense of the immediate neighbours. People grow up with a feeling of being hemmed in. Peace becomes a transient compromise between wars."[20] He described his experience in Warsaw as "useful, though not always joyful".[21] When he became pope, the Communist government of Poland refused him permission to visit Poland on a Marian pilgrimage.

Roman Curia

His organisational skills led him to a career in the Roman Curia, the papal civil service. On 19 October 1925, he was appointed a papal chamberlain in the rank of Supernumerary Privy Chamberlain of His Holiness.[22] In 1931, Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli appointed him to teach history at the Pontifical Academy for Diplomats;[17] he was promoted to Domestic Prelate of His Holiness on 8 July of the same year.[23] On 24 September 1936, he was appointed a Referendary Prelate of the Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura.[24]

On 16 December 1937,[25] after his mentor Giuseppe Pizzardo was named a cardinal and was succeeded by Domenico Tardini, Montini was named Substitute for Ordinary Affairs under Cardinal Pacelli, the Secretary of State. His immediate supervisor was Domenico Tardini, with whom he got along well. He was further appointed Consultor of the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office and of the Sacred Consistorial Congregation on 24 December,[26] and was promoted to Protonotary apostolic (ad instar participantium), the most senior class of papal prelate, on 10 May 1938.[27]

Pacelli became Pope Pius XII in 1939 and confirmed Montini's appointment as Substitute under the new Cardinal Secretary of State Luigi Maglione. In that role, roughly that of a chief of staff, he met the Pope every morning until 1954 and developed a rather close relationship with him. Of his service to two popes he wrote:

It is true, my service to the Pope was not limited to the political or extraordinary affairs according to Vatican language. The goodness of Pope Pius XII opened to me the opportunity to look into the thoughts, even into the soul of this great pontiff. I could quote many details how Pius XII, always using measured and moderate speech, was hiding, nay revealing a noble position of great strength and fearless courage.[28]

When war broke out, Maglione, Tardini, and Montini were the principal figures in the Secretariat of State of the Holy See.[29][page needed] Montini dispatched "ordinary affairs" in the morning, while in the afternoon he moved informally to the third floor Office of the Private Secretary of the Pontiff, serving in place of a personal secretary.[30] During the war years, he replied to thousands of letters from all parts of the world with understanding and prayer, and arranging for help when possible.[30]

At the request of the Pope, Montini created an information office regarding prisoners of war and refugees, which from 1939 to 1947 received almost ten million requests for information about missing persons and produced over eleven million replies.[31] Montini was several times attacked by Benito Mussolini's government for meddling in politics, but the Holy See consistently defended him.[32] When Maglione died in 1944, Pius XII appointed Tardini and Montini as joint heads of the Secretariat, each a Pro-Secretary of State. Montini described Pius XII with a filial admiration:

His richly cultivated mind, his unusual capacity for thought and study led him to avoid all distractions and every unnecessary relaxation. He wished to enter fully into the history of his own afflicted time: with a deep understanding, that he was himself a part of that history. He wished to participate fully in it, to share his sufferings in his own heart and soul.[33]

As Pro-Secretary of State, Montini coordinated the activities of assistance to persecuted fugitives hidden in Catholic convents, parishes, seminaries, and schools.[34] At the Pope's instruction, Montini, Ferdinando Baldelli, and Otto Faller established the Pontificia Commissione di Assistenza (Pontifical Commission for Assistance), which supplied a large number of Romans and refugees from everywhere with shelter, food and other necessities. In Rome alone it distributed almost two million portions of free food in 1944.[35] The Papal Residence of Castel Gandolfo was opened to refugees, as was Vatican City in so far as space allowed. Some 15,000 lived in Castel Gandolfo, supported by the Pontificia Commissione di Assistenza.[35] Montini was also involved in the re-establishment of Church Asylum, extending protection to hundreds of Allied soldiers escaped from prison camps, to Jews, anti-Fascists, Socialists, Communists, and after the liberation of Rome, to German soldiers, partisans, displaced persons and others.[36] As pope in 1971, Montini turned the Pontificia Commissione di Assistenza into Caritas Italiana.[37]

Archbishop of Milan

After the death of Cardinal Alfredo Ildefonso Schuster in 1954, Montini was appointed to succeed him as Archbishop of Milan, which made him the secretary of the Italian Bishops Conference.[38] Pius XII presented the new archbishop "as his personal gift to Milan". He was consecrated bishop in Saint Peter's Basilica by Cardinal Eugène Tisserant, the Dean of the College of Cardinals, since Pius XII was severely ill.

On 12 December 1954, Pius XII delivered a radio address from his sick-bed about Montini's appointment to the crowd in St. Peter's Basilica.[39] Both Montini and the Pope had tears in their eyes when Montini departed for his diocese with its 1,000 churches, 2,500 priests and 3,500,000 souls.[40] On 5 January 1955, Montini formally took possession of his Cathedral of Milan. Montini settled well into his new tasks among all groups of the faithful in the city, meeting cordially with intellectuals, artists and writers.[41]

Montini's philosophy

In his first months Montini showed his interest in working conditions and labour issues by speaking to many unions and associations. He initiated the building of over 100 new churches, believing them the only non-utilitarian buildings in modern society, places for spiritual rest.[42]

His public speeches were noticed not only in Milan but in Rome and elsewhere. Some considered him a liberal, when he asked lay people to love not only Catholics but also schismatics, Protestants, Anglicans, the indifferent, Muslims, pagans, and atheists.[43] He gave a friendly welcome to a group of Anglican clergy visiting Milan in 1957 and subsequently exchanged letters with the Archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Fisher.[44]

Pope Pius XII revealed at the 1952 secret consistory that both Montini and Tardini had declined appointments to the cardinalate[45][46] and in fact Montini was never to be made a cardinal by Pius XII, who held no consistory and created no cardinals from the time he appointed Montini to Milan and his own death four years later. After Montini's friend Angelo Roncalli became Pope John XXIII, he made Montini a cardinal in December 1958.

When the new pope announced an Ecumenical Council, Cardinal Montini reacted with disbelief and said to Giulio Bevilacqua: "This old boy does not know what a hornets nest he is stirring up."[47] Montini was appointed to the Central Preparatory Commission in 1961. During the council, Pope John XXIII asked him to live in the Vatican, where he was a member of the Commission for Extraordinary Affairs, though he did not engage much in the floor debates. His main advisor was Giovanni Colombo, whom he later appointed as his successor in Milan[48] The commission was greatly overshadowed by the insistence of John XXIII that the Council complete all its work before Christmas 1962, to coincide with the 400th anniversary of the Council of Trent, an insistence which may have also been influenced by the Pope's having recently been told that he had cancer.[49]

John had a vision but "did not have a clear agenda. His rhetoric seems to have had a note of over-optimism, a confidence in progress, which was characteristic of the 1960s."[50]

Pastoral progressivism

During his period in Milan, Montini was widely seen as a progressive member of the Catholic hierarchy. He adopted new approaches to reach the faithful with pastoral care, and carried through the liturgical reforms of Pius XII at the local level. For example, huge posters announced throughout the city that 1,000 voices would speak to them from 10 to 24 November 1957: more than 500 priests and many bishops, cardinals and lay people delivered 7,000 sermons, not only in churches but in factories, meeting halls, houses, courtyards, schools, offices, military barracks, hospitals, hotels and wherever people congregated.[51] His goal was the re-introduction of faith to a city without much religion. "If only we can say Our Father and know what this means, then we would understand the Christian faith."[52]

Pius XII asked Archbishop Montini to Rome October 1957, where he gave the main presentation to the Second World Congress of Lay Apostolate. As Pro-Secretary of State, he had worked hard to form this worldwide organisation of lay people in 58 nations, representing 42 national organisations. He had presented them to Pius XII in Rome in 1951. The second meeting in 1957 gave Montini an opportunity to express the lay apostolate in modern terms: "Apostolate means love. We will love all, but especially those, who need help... We will love our time, our technology, our art, our sports, our world."[53]

Cardinal

On 20 June 1958, Saul Alinsky recalled meeting with Montini: "I had three wonderful meetings with Montini and I am sure that you have heard from him since". Alinsky also wrote to George Nauman Shuster,[54] two days before the papal conclave that elected John XXIII: "No, I don't know who the next Pope will be, but if it's to be Montini, the drinks will be on me for years to come."[55]

Although some cardinals seem to have viewed Montini as a likely papabile candidate, possibly receiving some votes in the 1958 conclave,[56] he had the handicap of not yet being a cardinal.[a] Angelo Roncalli was elected pope on 28 October 1958 and took the name John XXIII. On 17 November 1958, L'Osservatore Romano announced a consistory for the creation of new cardinals, with Montini at the top of the list.[57] When the Pope raised Montini to the cardinalate on 15 December 1958, he became Cardinal-Priest of Ss. Silvestro e Martino ai Monti. The Pope appointed him simultaneously to several Vatican congregations, drawing him frequently to Rome in the coming years.[58]

Cardinal Montini journeyed to Africa in 1962, visiting Ghana, Sudan, Kenya, Congo, Rhodesia, South Africa, and Nigeria. After this journey, John XXIII called Montini to a private audience to report on his trip, speaking for several hours. In fifteen other trips he visited Brazil (1960) and the USA (1960), including New York City, Washington DC, Chicago, the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. He usually vacationed in Engelberg Abbey, a secluded Benedictine monastery in Switzerland.[59]

Papacy

| Papal styles of Pope Paul VI | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | Saint |

Papal conclave

Montini was generally seen as the most likely papal successor, being close to both Popes Pius XII and John XXIII, as well as his pastoral and administrative background, his insight, and his determination.[60] John XXIII had previously known the Vatican as an official until his appointment to Venice was a papal diplomat, but returning to Rome at age 66, he may at times have felt uncertain in dealing with the professional Roman Curia, but Montini had learned its innermost workings while working in it for a generation.[60]

Unlike the papabile cardinals Giacomo Lercaro of Bologna and Giuseppe Siri of Genoa, Montini was identified neither left nor right, nor as a radical reformer. He was viewed as most likely to continue the Second Vatican Council,[60] which had adjourned without tangible results.

In the conclave after John XXIII's death, Montini was elected pope on the sixth ballot, on 21 June. When the Dean of the College of Cardinals Eugène Tisserant asked if he accepted the election, Montini said "Accepto, in nomine Domini" ("I accept, in the name of the Lord"). He took the name "Paul VI," in honor of Paul the Apostle.[61]

At one point during the conclave on 20 June, it was said that Cardinal Gustavo Testa lost his temper and demanded that opponents of Montini halt their efforts to thwart his election.[62] Montini, fearful of causing strife, started to rise to dissuade the cardinals from voting for him, but Cardinal Giovanni Urbani dragged him back, muttering, "Eminence, shut up!"[63]

The white smoke first rose from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel at 11:22 am, when Protodeacon Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani announced to the public the successful election of Montini. When the new pope appeared on the central loggia, he gave the shorter episcopal blessing as his first apostolic blessing rather than the longer, traditional Urbi et Orbi.

Of the papacy, Paul VI wrote in his journal: "The position is unique. It brings great solitude. 'I was solitary before, but now my solitude becomes complete and awesome.'"[64]

Less than two years later, on 2 May 1965, Paul informed the dean of the College of Cardinals that his health might make it impossible to function as pope. He wrote that "In case of infirmity, which is believed to be incurable or is of long duration and which impedes us from sufficiently exercising the functions of our apostolic ministry; or in the case of another serious and prolonged impediment", he would renounce his office "both as bishop of Rome as well as head of the same holy Catholic Church".[65]

Reforms of papal ceremony

Paul VI did away with much of the papacy's regal splendor. His coronation on 30 June 1963 was the last such ceremony;[67] his successor Pope John Paul I substituted an inauguration (which Paul had substantially modified, but which he left mandatory in his 1975 apostolic constitution Romano Pontifici Eligendo). At his coronation Paul wore a tiara presented by the Archdiocese of Milan. At the end of the second session of the Second Vatican Council in 1963, Paul VI descended the steps of the papal throne in St. Peter's Basilica and ascended the altar, on which he laid the tiara as a sign of the renunciation of human glory and power in keeping with the innovative spirit of the council. It was announced that the tiara would be sold for charity.[68] The purchasers arranged for it to be displayed as a gift to American Catholics in the crypt of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C.

In 1968, with the motu proprio Pontificalis Domus, he discontinued most of the ceremonial functions of the old Papal nobility at the court (reorganized as the household), save for the Prince Assistants to the Papal Throne. He also abolished the Palatine Guard and the Noble Guard, leaving the Pontifical Swiss Guard as the sole military order of the Vatican.

Completion of the Vatican Council

Paul VI decided to reconvene Vatican II and brought it to completion in 1965. Faced with conflicting interpretations and controversies, he directed the implementation of its reform goals.

Ecumenical orientation

During Vatican II, the council fathers avoided statements which might anger Christians of other faiths.[69][page needed] Cardinal Augustin Bea, the President of the Christian Unity Secretariat, always had the full support of Paul VI in his attempts to ensure that the Council language was friendly and open to the sensitivities of Protestant and Orthodox Churches, whom he had invited to all sessions at the request of Pope John XXIII. Bea also was strongly involved in the passage of Nostra aetate, which regulates the church's relations with the Jewish faith and members of other religions.[b]

Dialogue with the world

After his election as Bishop of Rome, Paul VI first met with the priests in his new diocese. He told them that in Milan he started a dialogue with the modern world and asked them to seek contact with all people from all walks of life. Six days after his election he announced that he would continue Vatican II and convened the opening on 29 September 1963.[38] In a radio address to the world, Paul VI praised his predecessors, the strength of Pius XI, the wisdom and intelligence of Pius XII, and the love of John XXIII. As his pontifical goals he mentioned the continuation and completion of Vatican II, the reform of the Canon Law, and improved social peace and justice in the world. The Unity of Christianity would be central to his activities.[38]

Council priorities

The Pope re-opened the Ecumenical Council on 29 September 1963 giving it four key priorities:

- A better understanding of the Catholic Church

- Church reforms

- Advancing the unity of Christianity

- Dialogue with the world[38]

He reminded the Council Fathers that only a few years earlier Pope Pius XII had issued the encyclical Mystici corporis about the mystical body of Christ. He asked them not to repeat or create new dogmatic definitions but to explain in simple words how the church sees itself. He thanked the representatives of other Christian communities for their attendance and asked for their forgiveness if the Catholic Church was at fault for their separation. He also reminded the Council Fathers that many bishops from the east had been forbidden to attend by their national governments.[70]

Third and fourth sessions

Paul VI opened the third period on 14 September 1964, telling the Council Fathers that he viewed the text about the church as the most important document to come out from the council. As the Council discussed the role of bishops in the papacy, Paul VI issued an explanatory note confirming the primacy of the papacy, a step which was viewed by some as meddling in the affairs of the Council.[71] American bishops pushed for a speedy resolution on religious freedom, but Paul VI insisted this to be approved together with related texts such as ecumenism.[72] The Pope concluded the session on 21 November 1964, with the formal pronouncement of Mary as Mother of the Church.[72]

Between the third and fourth sessions the Pope announced reforms in the areas of Roman Curia, revision of Canon law, regulations for mixed marriages involving several faiths, and birth control issues. He opened the final session of the council, concelebrating with bishops from countries where the church was persecuted. Several texts proposed for his approval had to be changed. But all texts were finally agreed upon. The council was concluded on 8 December 1965, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception.[72]

In the final session of the council, Paul VI announced that he would open the canonisation processes of his immediate predecessors: Pope Pius XII and Pope John XXIII.

Universal call to holiness

According to Pope Paul VI, "the most characteristic and ultimate purpose of the teachings of the Council" is the universal call to holiness:[73] "all the faithful of Christ of whatever rank or status, are called to the fullness of the Christian life and to the perfection of charity; by this holiness as such a more human manner of living is promoted in this earthly society." This teaching is found in Lumen Gentium, the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, promulgated by Paul VI on 21 November 1964.

Church reforms

Synod of Bishops

On 14 September 1965, he established the Synod of Bishops as a permanent institution of the Catholic Church and an advisory body to the papacy. Several meetings were held on specific issues during his pontificate, such as the Synod of Bishops on evangelisation in the modern world, which started 9 September 1974.[74]

Curia reform

Pope Paul VI knew the Roman Curia well, having worked there for a generation from 1922 to 1954. He implemented his reforms in stages. On 1 March 1968, he issued a regulation, a process that had been initiated by Pius XII and continued by John XXIII. On 28 March, with Pontificalis Domus, and in several additional Apostolic Constitutions in the following years, he revamped the entire Curia, which included reduction of bureaucracy, streamlining of existing congregations and a broader representation of non-Italians in the curial positions.[75]

Age limits and restrictions

On 6 August 1966, Paul VI asked all bishops to submit their resignations to the pontiff by their 75th birthday. They were not required to do so but "earnestly requested of their own free will to tender their resignation from office".[76] He extended this request to all cardinals in Ingravescentem aetatem on 21 November 1970, with the further provision that cardinals would relinquish their offices in the Roman Curia upon reaching their 80th birthday.[77] These retirement rules enabled the Pope to fill several positions with younger prelates and reduce the Italian domination of the Roman Curia.[78] His 1970 measures also revolutionised papal elections by restricting the right to vote in papal conclaves to cardinals who had not yet reached their 80th birthday, a class known since then as "cardinal electors". This reduced the power of the Italians and the Curia in the next conclave. Some senior cardinals objected to losing their voting privilege, without effect.[79][80] Paul VI's measures also limited the number of cardinal-electors to a maximum of 120,[81] a rule disregarded on several occasions by his successors.

Some prelates questioned whether he should not apply these retirement rules to himself.[82] When Pope Paul was asked towards the end of his papacy whether he would retire at age 80, he replied "Kings can abdicate, Popes cannot."[83]

Liturgy

Reform of the liturgy, an aim of the 20th-century liturgical movement, mainly in France and Germany, was officially recognised as legitimate by Pius XII in his encyclical Mediator Dei. During his pontificate, he eased regulations on the obligatory use of Latin in Catholic liturgies, permitting some use of vernacular languages during baptisms, funerals and other events. In 1951 and 1955, he revised the Easter liturgies, most notably that of the Easter Triduum.[84] The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) gave some directives in its document Sacrosanctum Concilium for a general revision of the Roman Missal. Within four years of the close of the council, Paul VI promulgated in 1969 the first postconciliar edition, which included three new Eucharistic Prayers in addition to the Roman Canon, until then the only anaphora in the Roman Rite. Use of vernacular languages was expanded by decision of episcopal conferences, not by papal command. In addition to his revision of the Roman Missal, Pope Paul VI issued instructions in 1964, 1967, 1968, 1969 and 1970, reforming other elements of the liturgy of the Roman Church.[85]

These reforms were not universally welcomed. Questions were raised about the need to replace the 1962 Roman Missal, which, though decreed on 23 June 1962[86] became available only in 1963, a few months before the Second Vatican Council's Sacrosanctum Concilium decree ordered that it be altered;[87] but attachment to it led to open ruptures, of which the most widely known is that of Marcel Lefebvre. Pope John Paul II granted bishops the right to authorise use of the 1962 Missal (Quattuor abhinc annos and Ecclesia Dei) and in 2007 Pope Benedict XVI, while stating that the Mass of Paul VI and John Paul II "obviously is and continues to be the normal Form – the Forma ordinaria – of the Eucharistic Liturgy",[88] gave general permission to priests of the Latin Church to use either the 1962 Missal or the post-Vatican II Missal both privately and, under certain conditions, publicly.[89] In 2021, Pope Francis removed many of faculties granted by Pope Benedict XVI with the publishing of his motu proprio, Traditionis Custodes, thus limiting the use of 1962 Roman Missal.[90]

Relations and dialogues

To Paul VI, a dialogue with all of humanity was essential not as an aim but as a means to find the truth. Dialogue according to Paul, is based on full equality of all participants. This equality is rooted in the common search for the truth.[91] He said: "Those who have the truth, are in a position as not having it, because they are forced to search for it every day in a deeper and more perfect way. Those who do not have it, but search for it with their whole heart, have already found it."[91]

Dialogues

In 1964, Paul VI created a Secretariat for non-Christians, later renamed the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue and a year later a new Secretariat (later Pontifical Council) for Dialogue with Non-Believers. This latter was in 1993 incorporated by Pope John Paul II in the Pontifical Council for Culture, which he had established in 1982. In 1971, Paul VI created a papal office for economic development and catastrophic assistance. To foster common bonds with all persons of good will, he decreed an annual peace day to be celebrated on January first of every year. Trying to improve the condition of Christians behind the Iron Curtain, Paul VI engaged in dialogue with Communist authorities at several levels, receiving Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko and Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet Nikolai Podgorny in 1966 and 1967 in the Vatican. The situation of the church in Hungary, Poland and Romania, improved during his pontificate.[92]

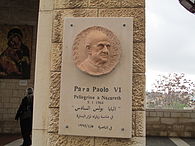

Foreign travelsedit

Pope Paul VI became the first pope to visit six continents. He was also the first pontiff to travel on an airplane, visit the Holy Land on pilgrimage, and travel outside of Italy in a century. He travelled more widely than any of his predecessors, earning the nickname "the Pilgrim Pope". He visited the Holy Land in 1964 and participated in Eucharistic Congresses in Bombay, India and Bogotá, Colombia. In 1966, he was twice denied permission to visit Poland for the 1,000th anniversary of the introduction of Christianity in Poland. In 1967, he visited the shrine of Our Lady of Fátima in Portugal on the fiftieth anniversary of the apparitions there. He undertook a pastoral visit to Uganda in 1969,[93] the first by a reigning pope to Africa.[94] Pope Paul VI became the first reigning pontiff to visit the Western hemisphere when he addressed the United Nations in New York City in October 1965.[c] As the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War was escalating, Paul VI pleaded for peace before the UN:

Our very brief visit has given us a great honour; that of proclaiming to the whole world, from the Headquarters of the United Nations, Peace! We shall never forget this extraordinary hour. Nor can We bring it to a more fitting conclusion than by expressing the wish that this central seat of human relationships for the civil peace of the world may ever be conscious and worthy of this high privilege.[99]

No more war, never again war. Peace, it is peace that must guide the destinies of people and of all mankind."[100]

Attempted assassinationedit

Shortly after arriving at Manila International Airport, Philippines on 27 November 1970, the Pope, closely followed by President Ferdinand Marcos and personal aide Pasquale Macchi, who was private secretary to Pope Paul VI, were encountered suddenly by a crew-cut, cassock-clad man who tried to attack the Pope with a knife. Macchi pushed the man away; police identified the would-be assassin as Benjamin Mendoza y Amor, 35, of La Paz, Bolivia. Mendoza was an artist living in the Philippines. The Pontiff continued with his trip and thanked Marcos and Macchi, who both had moved to protect him during the attack.[101]

New diplomacyedit

Like his predecessor Pius XII, Paul VI put much emphasis on the dialogue with all nations of the world through establishing diplomatic relations. The number of foreign embassies accredited to the Vatican doubled during his pontificate.[102] This was a reflection of a new understanding between church and state, which had been formulated first by Pius XI and Pius XII but decreed by Vatican II. The pastoral constitution Gaudium et spes stated that the Catholic Church is not bound to any form of government and willing to co-operate with all forms. The church maintained its right to select bishops on its own without any interference by the State.[103]

Pope Paul VI sent one of 73 Apollo 11 Goodwill Messages to NASA for the historic first lunar landing. The message still rests on the lunar surface today. It has the words of the 8th Psalm and the Pope wrote, "To the Glory of the name of God who gives such power to men, we ardently pray for this wonderful beginning."[104]

Theologyedit

Mariologyedit

Pope Paul VI made extensive contributions to Mariology (theological teaching and devotions) during his pontificate. He attempted to present the Marian teachings of the church in view of her new ecumenical orientation. In his inaugural encyclical Ecclesiam suam (section below), the Pope called Mary the ideal of Christian perfection. He regards "devotion to the Mother of God as of paramount importance in living the life of the Gospel."[105]

Encyclicalsedit

Paul VI authored seven encyclicals.

Ecclesiam suamedit

Ecclesiam suam was given at St. Peter's, Rome, on the Feast of the Transfiguration, 6 August 1964, the second year of his pontificate. It is considered an important document, identifying the Catholic Church with the Body of Christ. A later Council document Lumen gentium stated that the church subsists in the Body of Christ, raising questions as to the difference between "is" and "subsists in". Paul VI appealed to "all people of good will" and discussed necessary dialogues within the church and between the churches and with atheism.[74]

Mense maioedit

The encyclical Mense maio (from 29 April 1965) focused on the Virgin Mary, to whom traditionally the month of May is dedicated as the Mother of God. Paul VI writes that Mary is rightly to be regarded as the way by which people are led to Christ. Therefore, the person who encounters Mary cannot help but encounter Christ.[106]

Mysterium fideiedit

On 3 September 1965, Paul VI issued Mysterium fidei, on the mystery of the faith. He opposed relativistic notions which would have given the Eucharist a symbolic character only. The church, according to Paul VI, has no reason to give up the deposit of faith in such a vital matter.[74]

Christi Matriedit

On 15 September 1966, Paul VI issued Christi Matri, a request of the faithful to pray for peace during the month of October 1966. As reasons for this call to prayer, Paul VI alludes to the Vietnam War and lists concern about "the growing nuclear armaments race, the senseless nationalism, the racism, the obsession for revolution, the separations imposed upon citizens, the nefarious plots, the slaughter of innocent people."[107]

Populorum progressioedit

Populorum progressio, released on 26 March 1967, dealt with the topic of "the development of peoples" and that the economy of the world should serve mankind and not just the few. It touches on a variety of traditional principles of Catholic social teaching: the right to a just wage; the right to security of employment; the right to fair and reasonable working conditions; the right to join a union and strike as a last resort; and the universal destination of resources and goods.

In addition, Populorum progressio opines that real peace in the world is conditional on justice. He repeats his demands expressed in Bombay in 1964 for a large-scale World Development Organization, as a matter of international justice and peace. He rejected notions to instigate revolution and force in changing economic conditions.[108]

Sacerdotalis caelibatusedit

Sacerdotalis caelibatus (Latin for "Of the celibate priesthood"), promulgated on 24 June 1967, defends the Catholic Church's tradition of priestly celibacy in the West. This encyclical was written in the wake of Vatican II, when the Catholic Church was questioning and revising many long-held practices. Priestly celibacy is considered a discipline rather than dogma, and some had expected that it might be relaxed. In response to these questions, the Pope reaffirms the discipline as a long-held practice with special importance in the Catholic Church. The encyclical Sacerdotalis caelibatus from 24 June 1967, confirms the traditional church teaching, that celibacy is an ideal state and continues to be mandatory for Catholic priests. Celibacy symbolises the reality of the kingdom of God amid modern society. The priestly celibacy is closely linked to the sacramental priesthood.[74] However, during his pontificate Paul VI was permissive in allowing bishops to grant laicisation of priests who wanted to leave the sacerdotal state. John Paul II changed this policy in 1980 and the 1983 Code of Canon Law made it explicit that only the Pope can in exceptional circumstances grant laicisation.

Humanae vitaeedit

Of his seven encyclicals, Pope Paul VI is best known for his encyclical Humanae vitae (Of Human Life, subtitled On the Regulation of Birth), published on 25 July 1968. In this encyclical he reaffirmed the Catholic Church's traditional view of marriage and marital relations and its condemnation of artificial birth control.[109] There were two Papal committees and numerous independent experts looking into the latest advancement of science and medicine on the question of artificial birth control.[110] which were noted by the Pope in his encyclical[111] The expressed views of Paul VI reflected the teachings of his predecessors, especially Pius XI,[112] Pius XII[113] and John XXIII[114] and never changed, as he repeatedly stated them in the first few years of his Pontificate.[115]

To the Pope as to all his predecessors, marital relations are much more than a union of two people. They constitute a union of the loving couple with a loving God, in which the two persons create a new person materially, while God completes the creation by adding the soul. For this reason, Paul VI teaches in the first sentence of Humanae vitae that the transmission of human life is a most serious role in which married people collaborate freely and responsibly with God the Creator.[116] This divine partnership, according to Paul VI, does not allow for arbitrary human decisions, which may limit divine providence. The Pope does not paint an overly romantic picture of marriage: marital relations are a source of great joy, but also of difficulties and hardships.[116] The question of human procreation exceeds in the view of Paul VI specific disciplines such as biology, psychology, demography or sociology.[117] The reason for this, according to Paul VI, is that married love takes its origin from God, who "is love". From this basic dignity, he defines his position:

Love is total—that very special form of personal friendship in which husband and wife generously share everything, allowing no unreasonable exceptions and not thinking solely of their own convenience. Whoever really loves his partner loves not only for what he receives, but loves that partner for the partner's own sake, content to be able to enrich the other with the gift of himself.[118]

The reaction to the encyclical's continued prohibitions of artificial birth control was very mixed. In Italy, Spain, Portugal and Poland, the encyclical was welcomed.[119] In Latin America, much support developed for the Pope and his encyclical. As World Bank President Robert McNamara declared at the 1968 Annual Meeting of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group that countries permitting birth control practices would get preferential access to resources, doctors in La Paz, Bolivia called it insulting that money should be exchanged for the conscience of a Catholic nation. In Colombia, Cardinal archbishop Aníbal Muñoz Duque declared, "If American conditionality undermines Papal teachings, we prefer not to receive one cent".[120] The Senate of Bolivia passed a resolution stating that Humanae vitae could be discussed in its implications for individual consciences, but was of greatest significance because the papal document defended the rights of developing nations to determine their own population policies.[120] The Jesuit Journal Sic dedicated one edition to the encyclical with supportive contributions.[121]

Paul VI was concerned but not surprised by the negative reaction in Western Europe and the United States. He fully anticipated this reaction to be a temporary one: "Don't be afraid", he reportedly told Edouard Gagnon on the eve of the encyclical, "in twenty years time they'll call me a prophet."[122] His biography on the Vatican's website notes his reaffirmations of priestly celibacy and the traditional teaching on contraception that "the controversies over these two pronouncements tended to overshadow the last years of his pontificate".[123] Pope John Paul II later reaffirmed and expanded upon Humanae vitae with the encyclical Evangelium vitae.

Evangelismedit

By taking the name of Paul, the newly elected Pope showed his intention to take Paul the Apostle as a model for his papal ministry.[124] In 1967, when he reorganised the Roman curia, Pope Paul renamed the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith as the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples. Pope Paul was the first pope in history to make apostolic journeys to other continents and visited six continents.[124] The Pope chose the theme of evangelism for the synod of bishops in 1974. From materials generated by that synod, he composed the 1975 apostolic exhortation on evangelisation, Evangelii nuntiandi.[124]

Ecumenism and ecumenical relationsedit

After the council, Paul VI contributed in two ways to the continued growth of ecumenical dialogue. The separated brothers and sisters, as he called them, were not able to contribute to the council as invited observers. After the council, many of them took initiative to seek out their Catholic counterparts and the Pope in Rome, who welcomed such visits. But the Catholic Church itself recognised from the many previous ecumenical encounters, that much needed to be done within, to be an open partner for ecumenism.[125] To those who are entrusted the highest and deepest truth and therefore, so Paul VI, believed that he had the most difficult part to communicate. Ecumenical dialogue, in the view of Paul VI, requires from a Catholic the whole person: one's entire reason, will, and heart.[126] Paul VI, like Pius XII before him, was reluctant to give in on a lowest possible point. And yet, Paul felt compelled to admit his ardent Gospel-based desire to be everything to everybody and to help all people[127] Being the successor of Peter, he felt the words of Christ, "Do you love me more" like a sharp knife penetrating to the marrow of his soul. These words meant to Paul VI love without limits,[128] and they underscore the church's fundamental approach to ecumenism.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Pope_Paul_VI

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk