A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

Unemployment benefits, also called unemployment insurance, unemployment payment, unemployment compensation, or simply unemployment, are payments made by governmental bodies to unemployed people. Depending on the country and the status of the person, those sums may be small, covering only basic needs, or may compensate the lost time proportionally to the previous earned salary.

Unemployment benefits are generally given only to those registering as becoming unemployed through no fault of their own, and often on conditions ensuring that they seek work.

In British English, unemployment benefits are also colloquially referred to as "the dole";[1][2] receiving benefits is informally called "being on the dole".[3] "Dole" here is an archaic expression meaning "one's allotted portion", from the synonymous Old English word dāl.[4] In Australia, a "dole bludger" is someone on unemployment benefits who makes no effort to find work.[5]

History

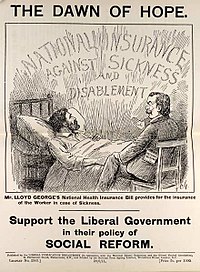

The first modern unemployment benefit scheme was introduced in the United Kingdom with the National Insurance Act 1911, under the Liberal Party government of H. H. Asquith. The popular measures were introduced to stave off poverty inflicted through unemployment, though they also gave the Liberal Party the added benefit of combatting the Labour Party's increasing influence among the country's working-class population. The Act gave the British working classes a contributory system of insurance against illness and unemployment. It only applied to wage earners, however, and their families and the unwaged had to rely on other sources of support, if any.[6] Key figures in the implementation of the Act included Robert Laurie Morant and William Braithwaite.

By the time of its implementation, the benefits were criticized by communist parties, who saw such insurance as a means to prevent workers from starting a revolution, while employers and tories sometimes saw it as a "necessary evil".[7]

The scheme was based on actuarial principles and was funded by fixed amounts from workers, employers, and taxpayers. It was restricted to particular industries, particularly more volatile ones like shipbuilding, and did not make provision for any dependants. After one week of unemployment, a worker was eligible to receive seven shillings per week for up to 15 weeks in a year. By 1913, 2.3 million were insured under the unemployment benefit program.

Expansion and spread

The Unemployment Insurance Act 1920 created the dole system of payments for unemployed workers in the United Kingdom.[8] The dole system provided 39 weeks of unemployment benefits to over 11 million workers—practically the entire civilian working population except domestic service, farmworkers, railroad men, and civil servants.

Unemployment benefits were introduced in Germany in 1927, and in most European countries in the period after the Second World War with the expansion of the welfare state. Unemployment insurance in the United States originated in Wisconsin in 1932.[9] Through the Social Security Act of 1935, the federal government of the United States effectively encouraged the individual states to adopt unemployment insurance plans.

Processes

Eligibility criteria for unemployment benefits typically factor in the applicant's employment history and their reason for being unemployed. Once approved, there is sometimes a waiting period before being able to receive benefits. In the US, there is no waiting period on a temporary basis currently due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but in many states there is a waiting week. In Germany and Belgium, there is no waiting week. The current waiting period in Canada is seven days. Countries implement varied potential benefit durations (PBD), which is how long an individual is eligible to receive benefits. The PBD may be a sliding scale function of the applicant's past employment history and age, or it may be a set length for all applicants. In Argentina, for example, six months of work history results in a PBD of two months, while 36 months or more of work history can result in a PBD of a full year, with an extra six months of PBD to applicants over the age of 45.[10]

Most countries calculate the amount of unemployment benefit as a percentage of the applicant's former income. A typical replacement percentage is 50–65%. Some countries offer much higher levels of wage replacement, such as the Netherlands (75%), Luxembourg (80%), and Denmark (90%). There are often caps on the maximum benefit level, ranging from 33% of a country's average wage (Turkey) to 227% of its average wage (France). The average maximum benefit level is 77% among OECD countries. Most benefit payments are constant over the course of the PBD, though countries such as the Netherlands, Sweden, Hungary, Slovenia, Spain, and Italy have a declining benefit path, in which the wage replacement percentage decreases over time.[10]

Most countries require those receiving unemployment benefits to search for a new job, and can require documentation of job search activities. Benefits may be cut if the applicant does not fulfil the search requirements, or turns down a job offer deemed acceptable by the unemployment benefits agency. Agencies may also provide resources, training, or education for job seekers. Some countries allow beneficiaries to accept part-time jobs without losing benefit eligibility, which can counter the disincentive of unemployment benefits to accepting jobs that do not fully replace the former wages.[10]

Unemployment benefits are typically funded by payroll taxes on employers and employees. This can be supplemented by the government's general tax revenue, which can occur periodically or in response to economic downturn. Contribution rates are usually between 1 and 3% of gross earnings, and are usually split between the employer and employee.[10]

Systems by country

Across the world, 72 countries offer a form of unemployment benefits. This includes all 37 OECD countries. Among OECD countries for a hypothetical 40-year-old unemployment benefit applicant, the US and Slovakia are the least generous for potential benefit duration lengths, with PBD of six months. More generous OECD countries are Sweden (35 months PBD) and Iceland (36 months PBD); in Belgium, the PBD is indefinite.[10]

Armenia

Armenia's Unemployment Insurance (UI) scheme has been in force since 1991. In 2005, Armenia adopted the law on Employment of the Population and Social Protection in Case of Unemployment, which provided a legal framework to the Unemployment Insurance and active labor policies. Armenia's UI is a contributory program, which is obligatory for public and formal private sectors, as well as the self-employed. To be eligible for benefits, the claimant must be unemployed as a result of business reorganization, staff reduction, or the termination of a collective bargaining agreement. To be eligible, applicants must have contributed for at least 12 months prior to unemployment or be actively looking for work after a long period of unemployment. The UI is also available to first-time job seekers. Those who do not qualify for the monthly payment are nonetheless eligible for the UI scheme's capacity building programs. Those who qualify for the monthly unemployment benefit will get a payment of 18,000 AMD per month for a minimum of 6 months and a maximum of 12 months.

The UI also includes a scheme to help employers hire people who are unemployed with at least 35 years of UI contributions but have not reached retirement age; unemployed for more than three years; returning from corrective or medical institutions; returning from mandatory military service; disabled; refugees; or are 16 years of age and newly eligible to work. Employers who hire these groups are eligible for a benefit of 50% of the minimum wage to supplement the employee's income. The UI also provides financial assistance and capacity-building programs for unemployed or disabled individuals who want to start their own businesses. Armenia also has a Paid Public Works program that provides jobseekers and the disabled with temporary public employment for three months.

Australia

This section needs to be updated. (July 2020) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

In Australia, social security benefits, including unemployment benefits, are funded through the taxation system. There is no compulsory national unemployment insurance fund. Rather, benefits are funded in the annual Federal Budget by the National Treasury and are administrated and distributed throughout the nation by the government agency, Centrelink. Benefit rates are indexed to the Consumer Price Index and are adjusted twice a year according to inflation or deflation.

There are two types of payment available to those experiencing unemployment. The first, called Youth Allowance, is paid to young people aged 16–20 (or 15, if deemed to meet the criteria for being considered 'independent' by Centrelink). Youth Allowance is also paid to full-time students aged 16–24, and to full-time Australian Apprenticeship workers aged 16–24. People aged below 18 who have not completed their high school education, are usually required to be in full-time education, undertaking an apprenticeship or doing training to be eligible for Youth Allowance. For single people under 18 years of age living with a parent or parents, the basic rate is A$91.60 per week. For over-18- to 20-year-olds living at home this increases to A$110.15 per week. For those aged 18–20 not living at home the rate is A$167.35 per week. There are special rates for those with partners and/or children.

The second kind of payment is called 'JobSeeker Payment' (called Newstart until 20 June 2020) and is paid to unemployed people over the age of 21 and under the pension eligibility age. To receive a JobSeeker Payment, recipients must be unemployed, be prepared to enter into an Employment Pathway Plan (previously called an Activity Agreement) by which they agree to undertake certain activities to increase their opportunities for employment, be Australian Residents and satisfy the income test (which limits weekly income to A$32 per week before benefits begin to reduce, until one's income reaches A$397.42 per week at which point no unemployment benefits are paid) and the assets test (an eligible recipient can have assets of up to A$161,500 if he or she owns a home before the allowance begins to reduce and $278,500 if he or she does do not own a home). The rate of allowance as of 12 January 2010 for single people without children was A$228 per week, paid fortnightly. (This does not include supplemental payments such as Rent Assistance or Energy Supplement.[11]) Different rates apply to people with partners and/or children.

Effectively, people have had to survive on $39 a day since 1994, and there have been calls to raise this by politicians and NGO groups.[12] On 22 February 2021, the Prime Minister of Australia, Scott Morrison, announced that the JobSeeker base rate would be increased by A$50 a fortnight from April 2021. It is also intended to increase the threshold amount recipients can earn before their payment starts to be reduced.[13]

The system in Australia is designed to support recipients no matter how long they have been unemployed. In recent years the former Coalition government under John Howard has increased the requirements of the Activity Agreement, providing for controversial schemes such as Work for the Dole, which requires that people on benefits for 6 months or longer work voluntarily for a community organisation regardless of whether such work increases their skills or job prospects. Since the Labor government under Kevin Rudd was elected in 2008, the length of unemployment before one is required to fulfill the requirements of the Activity Agreement (which has been renamed the Employment Pathway Plan) has increased from six to twelve months. There are other options available as alternatives to the Work for the Dole scheme, such as undertaking part-time work or study and training, the basic premise of the Employment Pathway Plan being to keep the welfare recipient active and involved in seeking full-time work.

For people renting their accommodation, unemployment benefits are supplemented by Rent Assistance, which, for single people as at 20 September 2021, begins to be paid when fortnightly rent is more than A$124.60. Rent Assistance is paid as a proportion of total rent paid (75 cents per dollar paid over A$124.60 up to the maximum). The maximum amount of rent assistance payable is A$139.60 per fortnight, and is paid when the total weekly rent exceeds A$310.73 per fortnight. Different rates apply to people with partners and/or children, or who are sharing accommodation.[14]

Canada

In Canada, the system is known as "Employment Insurance" (EI, French: Prestations d’assurance-emploi). Formerly called "Unemployment Insurance", the name was changed in 1996. In 2024, Canadian workers paid premiums of 1.66%[15] of insured earnings in return for benefits if they lose their jobs.

The Employment and Social Insurance Act was passed in 1935 during the Great Depression by the government of R. B. Bennett as an attempted Canadian unemployment insurance program. It was, however, ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of Canada as unemployment was judged to be an insurance matter falling under provincial responsibility. After a constitutional amendment was agreed to by all of the provinces, a reference to "Unemployment Insurance" was added to the matters falling under federal authority under the Constitution Act, 1867, and the first Canadian system was adopted in 1940. Because of these problems Canada was the last major Western country to bring in an employment insurance system. It was extended dramatically by Pierre Trudeau in 1971 making it much easier to get. The system was sometimes called the 10/42, because one had to work for 10 weeks to get benefits for the other 42 weeks of the year. It was also in 1971 that the UI program was first opened up to maternity and sickness benefits, for 15 weeks in each case.

The generosity of the Canadian UI program was progressively reduced after the adoption of the 1971 UI Act. At the same time, the federal government gradually reduced its financial contribution, eliminating it entirely by 1990. The EI system was again cut by the Progressive Conservatives in 1990 and 1993, then by the Liberals in 1994 and 1996. Amendments made it harder to qualify by increasing the time needed to be worked, although seasonal claimants (who work long hours over short periods) turned out to gain from the replacement, in 1996, of weeks by hours to qualify. The ratio of beneficiaries to unemployed, after having stood at around 40% for many years, rose somewhat during the 2009 recession but then fell back again to the low 40s.[16] Some unemployed persons are not covered for benefits (e.g. self-employed workers), while others may have exhausted their benefits, did not work long enough to qualify, or quit or were dismissed from their job. The length of time one could take EI has also been cut repeatedly. The 1994 and 1996 changes contributed to a sharp fall in Liberal support in the Atlantic provinces in the 1997 election.

In 2001, the federal government increased parental leave from 10 to 35 weeks, which was added to preexisting maternity benefits of 15 weeks. In 2004, it allowed workers to take EI for compassionate care leave while caring for a dying relative, although the strict conditions imposed make this a little used benefit. In 2006, the Province of Quebec opted out of the federal EI scheme in respect of maternity, parental and adoption benefits, in order to provide more generous benefits for all workers in that province, including self-employed workers. Total EI spending was $19.677 billion for 2011–2012 (figures in Canadian dollars).[17]

Employers contribute 1.4 times the amount of employee premiums. Since 1990, there is no government contribution to this fund. The amount a person receives and how long they can stay on EI varies with their previous salary, how long they were working, and the unemployment rate in their area. The EI system is managed by Service Canada, a service delivery network reporting to the Minister of Employment and Social Development Canada.

A bit over half of EI benefits are paid in Ontario and the Western provinces but EI is especially important in the Atlantic provinces, which have higher rates of unemployment. Many Atlantic workers are also employed in seasonal work such as fishing, forestry or tourism and go on EI over the winter when there is no work. There are special rules for fishermen making it easier for them to collect EI. EI also pays for maternity and parental leave, compassionate care leave, and illness coverage. The program also pays for retraining programs (EI Part II) through labour market agreements with the Canadian provinces.

A significant part of the federal fiscal surplus of the Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin years came from the EI system. Premiums were reduced much less than falling expenditures – producing, from 1994 onwards, EI surpluses of several billion dollars per year, which were added to general government revenue.[18] The cumulative EI surplus stood at $57 billion at 31 March 2008,[19] nearly four times the amount needed to cover the extra costs paid during a recession.[20] This drew criticism from Opposition parties and from business and labour groups, and has remained a recurring issue of the public debate. The Conservative Party,[21] chose not to recognize those EI surpluses after being elected in 2006. Instead, the Conservative government cancelled the EI surpluses entirely in 2010, and required EI contributors to make up the 2009, 2010 and 2011 annual deficits by increasing EI premiums. On 11 December 2008, the Supreme Court of Canada rejected a court challenge launched against the federal government by two Quebec unions, who argued that EI funds had been misappropriated by the government.[22]

China

The level of benefit is set between the minimum wage and the minimum living allowance by individual provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities.[23]

Denmark

European Union

Each Member State of the European Union has its own system and, in general, a worker should claim unemployment benefits in the country where they last worked. For a person working in a country other than their country of residency (a cross-border worker), they will have to claim benefits in their country of residence.[24]

Finland

Two systems run in parallel, combining a Ghent system and a minimum level of support provided by Kela, an agency of the national government. Unionization rates are high (70%), and union membership comes with membership in an unemployment fund. Additionally, there are non-union unemployment funds. Usually, benefits require 26 weeks of 18 hours per week on average, and the unemployment benefit is 60% of the salary and lasts for 500 days.[25] When this is not available, Kela can pay either regular unemployment benefit or labor market subsidy benefits. The former requires a degree and two years of full-time work. The latter requires participation in training, education, or other employment support, which may be mandated on pain of losing the benefit, but may be paid after the regular benefits have been either maxed out or not available.[26] Although the unemployment funds handle the payments, most of the funding is from taxes and compulsory tax-like unemployment insurance charges.

Regardless of whether benefits are paid by Kela or from an unemployment fund, the unemployed person receives assistance from the Työ- ja elinkeinokeskus (TE-keskus, or the "Work and Livelihood Centre"), a government agency which helps people to find jobs and employers to find workers. In order to be considered unemployed, the seeker must register at the TE-keskus as unemployed. If the jobseeker does not have degree, the agency can require the job seeker to apply to a school.

If the individual does not qualify for any unemployment benefit he may still be eligible for the housing benefit (asumistuki) from Kela and municipal social welfare provisions (toimeentulotuki). They are not unemployment benefits and depend on household income, but they have in practice become the basic income of many long-term unemployed.

France

France uses a quasi Ghent system, under which unemployment benefits are distributed by an independent agency (UNEDIC) in which unions and Employer organisations are equally represented.[27] UNEDIC is responsible for 3 benefits: ARE, ACA and ASR The main ARE scheme requires a minimum of 122 days membership in the preceding 24 months and certain other requirements before any claims can be made. Employers pay a contribution on top of the pre-tax income of their employees, which together with the employee contribution, fund the scheme.

The maximum unemployment benefit is (as of March 2009) 57.4% of EUR 162 per day (Social security contributions ceiling in 2011), or 6900 euros per month.[28] Claimants receive 57,4% of their average daily salary of the last 12 months preceding unemployment with the average amount being 1,111 euros per month.[29] In France tax and other payroll taxes are paid on unemployment benefits. In 2011 claimants received the allowance for an average 291 days.

Germany

Germany has two different types of unemployment benefits. Their common goal is to cease dependence on unemployment benefits entirely. Both programs assist their beneficiaries to varying degrees through

- a living allowance,

- help in finding work or training, and

- if necessary, getting state-funded training.

Unemployment benefit I

Unemployment benefits I is the first-tier program supporting unemployed people. It is designed like an insurance, involuntary unemployment through no personal fault being the "event of damage". It is therefore also known as unemployment insurance (Arbeitslosenversicherung).

In order to qualify, the unemployed person

- must have made contributions for at least 12 months in the past 30-month period,

- be unemployed, and

- be able to work now or at least in the foreseeable future.

All workers with a regular employment contract (abhängig Beschäftigte), except freelancers and certain civil servants (Beamte), contribute to the system. It is financed by contributions from employees and employers. This is in stark contrast to FUTA in the US and other systems, where only employers make contributions. Participation (and thus contributions) are generally mandatory for both employee and employer.

Employees pay 1.5% of their gross salary below the social security threshold and employers pay 1.5% contribution on top of the salary paid to the employee. The contribution level was reduced from 3.25% for employees and employers as part of labour market reforms known as Hartz. Contributions are paid only on earnings up to the social security ceiling (2012: 5,600 EUR). Furthermore, the system is supported by funds from the federal budget.

Claimants get 60% of their previous net salary (capped at the social security ceiling), or 67% for claimants with children (as long as beneficiary of child benefit). The maximum benefit is therefore 2964 euros (in 2012). If the benefits fall below the poverty line, it is possible to supplement unemployment benefits I with unemployment benefits II if its conditions are met as well.

Unemployment benefits I is only granted for a limited period of time, the minimum being 6 months, and the maximum 24 months in the case of old and long-term insured people. This takes account for the difficulty older people face when re-entering the job market in Germany.

Unlike unemployment benefits II, there is no means test. However, it is necessary to remain unemployed while seeking for employment. In this context unemployment is defined as working less than 15 hours a week.

Unemployment benefit II

Arbeitslosengeld II is a second tier, open-ended welfare programme intended to ensure people do not fall into penury.

- In order to be eligible, a person has to permanently reside in Germany, be in possession of a work permit, and be fit for work, i.e. can principally work at least three hours a day. The goal of the programme is to terminate one's dependence on it (welfare-to-work). It is not a Universal Basic Income.

- The benefits are subordinated, that means:

- A person may not eligible for other programmes, especially Unemployment benefits I and pension, but also other legal claims – e.g. dependence on parents, or accounts receivable – can not come to fruition.

- The person has to be in need (means test): He can not afford a minimum standard living by all incomes in total, or by expending his own previously accumulated assets, e.g. by selling real estate not required or adequate for a bare minimum lifestyle. In the course of the SARS-CoV‑2 pandemic these harsh standards have temporarily been reduced to a mere sanity check to avoid undue hardship.

Despite its name, unemployment is not a requirement. Due to wage dumping and other labour market dynamics, a large number of working beneficiaries supplement their monthly income. They have the same obligations as non-working beneficiaries.

People receiving benefits are obligated to cease their eligibility at all costs, but at least minimise their dependence on welfare until no money would be paid. That means, they are obliged to seek for jobs nationwide, and accept every job offered, otherwise sanctions (retrenchment) may be applied. There is no recognition of professional qualifications: An academic has to join the menial workforce, regardless of the waste of qualifications. Neither are one's personal religious or ethical concerns relevant: Prostitution is legal in Germany (although as of 2021 no job center has urged any beneficiary to engage in prostitution).

In exchange for that, beneficiaries are assisted in that process, e.g. by reimbursing travel expenses to interviews, receiving (free of charge) training in order to increase their chances on the labour market, or subsidising moving expenses once an employment contract has been signed but the place of work requires relocation as it is further than the acceptable daily commute duration (at most 3 hrs a day).

If they do not voluntarily participate in training, they may be obliged by administrative action.

Beneficiaries not complying with orders can be sanctioned by pruning their allowance and eventually revoking the grant altogether, virtually pushing them into poverty, homelessness and bankruptcy, as there are no other precautions installed.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Unemployment_benefits

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk