A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Zionism (/ˈzaɪ.ənɪzəm/ ZY-ə-niz-əm; Hebrew: צִיּוֹנוּת, romanized: Ṣīyyonūt, IPA: [tsijoˈnut]; derived from Zion) is an ethnic or ethno-cultural nationalist[1][fn 1] movement that emerged in Europe in the late 19th century that aimed for the establishment of a homeland for the Jewish people through the colonization of the region of Palestine,[4][5][6] a region corresponding to the Land of Israel in Jewish tradition,[7][8][9][10] an area with deep historical, national and religious importance in Jewish identity, history and religion.[11] Following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, Zionism became an ideology that supports the development and protection of Israel as a Jewish state.[1][12][13] It has also been described as Israel's national or state ideology.[14]

Zionism initially emerged in Central and Eastern Europe as a national revival movement in the late 19th century, in reaction to newer waves of antisemitism and as a consequence of the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment.[1][15][16][17] During this period, Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire.[18][19][20] The arrival of Zionist settlers to Palestine during this period is widely seen as the start of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Throughout the first decade of the Zionist movement, some Zionist figures, including Theodor Herzl, supported alternative options to Palestine in several places such as "Uganda" (actually parts of British East Africa today in Kenya), Argentina, Cyprus, Mesopotamia, Mozambique, and the Sinai Peninsula,[21] but this was rejected by most of the movement. This process was seen by the emerging Zionist movement as an "ingathering of exiles" (kibbutz galuyot), an effort to put a stop to the exoduses and persecutions that have marked Jewish history by bringing the Jewish people back to their historic homeland.[22]

From 1897 to 1948, the primary goal of the Zionist movement was to establish the basis for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, and thereafter to consolidate it. In a unique variation of the principle of self-determination,[23] the Lovers of Zion united in 1884, and in 1897 the first Zionist congress was organized. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a large number of Jews immigrated first to Ottoman and later to Mandatory Palestine. At the same time, some international recognition and support was gained, notably in the 1917 Balfour Declaration by the United Kingdom. Since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, Zionism has continued primarily to advocate on behalf of Israel and to address threats to its continued existence and security.

The term "Zionism" has been applied to various approaches to addressing issues faced by European Jews in the late 19th century.[24] Modern political Zionism, different from religious Zionism, is a movement made up of diverse political groups whose strategies and tactics have changed over time. The common ideology among mainstream Zionist factions is support for territorial concentration and a Jewish demographic majority in Palestine. The Zionist mainstream has historically included liberal, labor, revisionist, and cultural Zionism, while groups like Brit Shalom and Ihud have been dissident factions within the movement.[25] Differences within the mainstream Zionist groups lie primarily in their presentation and ethos, having adopted similar political strategies and approaches to dealing with the local Palestinian population, especially regarding the use of violence and compulsory transfer.[26][27][28][29][30] Advocates of Zionism have viewed it as a national liberation movement for the repatriation of an indigenous people (which were subject to persecution and share a national identity through national consciousness), to the homeland of their ancestors as noted in ancient history.[31][32][33] Similarly, anti-Zionism has many aspects, which include criticism of Zionism as a colonialist,[34] racist,[35] or exceptionalist ideology or as a settler colonialist movement.[36][37][38][39][40] Proponents of Zionism do not necessarily reject the characterization of Zionism as settler-colonial or exceptionalist.[41][42][43]

Terminology

The term "Zionism" is derived from the word Zion (Hebrew: ציון, romanized: Tzi-yon), a hill in Jerusalem, widely symbolizing the Land of Israel.[44] Throughout eastern Europe in the late 19th century, numerous grassroots groups promoted the national resettlement of the Jews in their homeland,[45] as well as the revitalization and cultivation of the Hebrew language. These groups were collectively called the "Lovers of Zion" and were seen as countering a growing Jewish movement toward assimilation. The first use of the term is attributed to the Austrian Nathan Birnbaum, founder of the Kadimah nationalist Jewish students' movement; he used the term in 1890 in his journal Selbst-Emancipation (Self-Emancipation),[46][47] itself named almost identically to Leon Pinsker's 1882 book Auto-Emancipation.

Overview

The common denominator among all modern Zionists is a claim to Palestine, a land traditionally known in Jewish writings as the Land of Israel ("Eretz Israel") as a national homeland of the Jews and as the legitimate focus for Jewish national self-determination.[48] Historically, the consensus in Zionist ideology has been that a Jewish national home requires a Jewish majority.[49] Zionism is based on historical ties and religious traditions linking the Jewish people to the Land of Israel.[50] Zionism does not have a uniform ideology, but modern political Zionism is typically associated with Labor Zionism and Revisionist Zionism which are not fundamentally different.[51][30][49]

For approximately 1,700 years after the last recorded Jewish majority in the region, most Jews lived in various countries without a national state as part of the post-Roman chapter of the Jewish diaspora.[52] The Zionist movement was founded in the late 19th century by secular Jews, largely as a response by Ashkenazi Jews to rising antisemitism in Europe, exemplified by the Dreyfus affair in France and the anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire.[53] The political movement was formally established by the Austro-Hungarian journalist Theodor Herzl in 1897 following the publication of his book Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State).[54] At that time, Herzl believed that Jewish migration to Ottoman Palestine, particularly among poor Jewish communities, unassimilated and whose 'floating' presence caused disquiet, would be beneficial to assimilated European Jews and Christians.[55] Political Zionism was in some respects a dramatic break from the two thousand years of Jewish and rabbinical tradition. Deriving inspiration from other European nationalist movements, Zionism drew in particular from a German version of European enlightenment thought, with German nationalistic principles becoming key features of Zionist nationalism. The Jewish historian of nationalism Hans Kohn argued that Zionism nationalism "had nothing to do with Jewish traditions; it was in many ways opposed to them". Starting early on, Zionism had its critics, the cultural Zionist Ahad Ha'am in the early 20th century wrote that there was no creativity in Herzl's Zionist movement, and that its culture was European and specifically German. He viewed the movement as depicting Jews as simple transmitters of imperialist European culture.[56]

Although initially one of several Jewish political movements offering alternative responses to Jewish assimilation and antisemitism, Zionism expanded rapidly. In its early stages, supporters considered setting up a Jewish state in the historic territory of Palestine. After World War II and the destruction of Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe where these alternative movements were rooted, it became dominant in the thinking about a Jewish national state. During this period, Zionism would develop a discourse in which the religious, non-Zionist Jews of the Old Yishuv who lived in mixed Arab-Jewish cities were viewed as backwards in comparison to the secular Zionist New Yishuv.[56]

From the beginning of the development of the Zionism movement, the support of the European powers was seen as necessary by the Zionist leadership (Herzl, Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion). Creating an alliance with Great Britain and securing support for some years for Jewish emigration to Palestine, Zionists also recruited European Jews to immigrate there, especially Jews who lived in areas of the Russian Empire where antisemitism was raging. The alliance with Britain was strained as the latter realized the implications of the Jewish movement for Arabs in Palestine, but the Zionists persisted. The movement was eventually successful in establishing Israel on May 14, 1948 (5 Iyyar 5708 in the Hebrew calendar), as the homeland for the Jewish people. The proportion of the world's Jews living in Israel has steadily grown since the movement emerged. By the early 21st century, more than 40% of the world's Jews lived in Israel, more than in any other country. These two outcomes represent the historical success of Zionism and are unmatched by any other Jewish political movement in the past 2,000 years. In some academic studies, Zionism has been analyzed both within the larger context of diaspora politics and as an example of modern national liberation movements.[57]

Zionism also sought the assimilation of Jews into the modern world. As a result of the diaspora, many of the Jewish people remained outsiders within their adopted countries and became detached from modern ideas. So-called "assimilationist" Jews desired complete integration into European society. They were willing to downplay their Jewish identity and in some cases to abandon traditional views and opinions in an attempt at modernization and assimilation into the modern world. A less extreme form of assimilation was called cultural synthesis. Those in favor of cultural synthesis desired continuity and only moderate evolution, and were concerned that Jews should not lose their identity as a people. "Cultural synthesists" emphasized both a need to maintain traditional Jewish values and faith and a need to conform to a modernist society, for instance, in complying with work days and rules.[58]

In 1975, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 3379, which designated Zionism as "a form of racism and racial discrimination". Resolution 3379 was repealed in 1991 with Israel's conditioning of its participation in the Madrid peace talks on the passing of Resolution 46/86, which “ revoke the determination contained in” 3379.[59]

Beliefs

Ethnic unity and descent from Biblical Jews

This article may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (April 2024) |

Early Zionists were the primary Jewish supporters of the idea that Jews are a race, as it "offered scientific 'proof' of the ethno-nationalist myth of common descent".[60] Zionist nationalism drew from a German ethnic-nationalist theory that people of common descent should seek separation and pursue the formation of their own state.[56][page needed] In the words of Yulia Egorova, this "racialisation of Jewish identity in the rhetoric of the founders of Zionism" was originally a reaction to European antisemitism.[61] According to Raphael Falk, as early as the 1870s, contrary to largely cultural perspectives among integrated and assimilated Jewish communities in the Age of Enlightenment and Age of Romanticism, "the Zionists-to-be stressed that Jews were not merely members of a cultural or a religious entity, but were an integral biological entity".[62] This re-conceptualization of Jewishness cast the "volk" of the Jewish community as a nation-race, in contrast to centuries-old conceptions of the Jewish people as a religious socio-cultural grouping.[62] The Jewish historians Heinrich Graetz and Simon Dubnow are largely credited with this creation of Zionism as a nationalist project. They drew on religious Jewish sources and non-Jewish texts in reconstructing a national identity and consciousness. This new Jewish historiography divorced from and, at times at odds with, traditional Jewish collective memory.[56]

It was particularly important in early nation building in Israel, because Jews in Israel are ethnically diverse and the origins of Ashkenazi Jews, the original founders of Zionism, are "highly debated and enigmatic".[63][64] Notable proponents of this racial idea included Max Nordau, Herzl's co-founder of the original Zionist Organization, Ze'ev Jabotinsky, the prominent architect of early statist Zionism and the founder of what became Israel's Likud party,[65] and Arthur Ruppin, considered the "father of Israeli sociology".[66] Jabotinsky wrote that Jewish national integrity relies on “racial purity", whereas Nordau asserted the need for an "exact anthropological, biological, economic, and intellectual statistic of the Jewish people".[65]

According to Hassan S. Haddad, the application of the Biblical concepts of Jews as the chosen people and the "Promised Land" in Zionism, particularly to secular Jews, requires the belief that modern Jews are the primary descendants of biblical Jews and Israelites.[67] This is considered important to the State of Israel, because its founding narrative centers around the concept of an "Ingathering of the exiles" and the "Return to Zion", on the assumption that all modern Jews are the direct lineal descendants of the biblical Jews.[68] The question has thus been focused on by supporters of Zionism and anti-Zionists alike,[69] as in the absence of this biblical primacy, "the Zionist project falls prey to the pejorative categorization as ‘settler colonialism’ pursued under false assumptions, playing into the hands of Israel's critics and fueling the indignation of the displaced and stateless Palestinian people,"[68] whilst right-wing Israelis look for "a way of proving the occupation is legitimate, of authenticating the ethnos as a natural fact, and of defending Zionism as a return".[70] A Jewish "biological self-definition" has become a standard belief for many Jewish nationalists, and most Israeli population researchers have never doubted that evidence will one day be found, even though so far proof for the claim has "remained forever elusive".[71]

Rejection of the Identity of the Diaspora Jew

Israeli-Irish scholar Ronit Lentin has argued that the construction of Zionist identity as a militarized nationalism arose in contrast to the imputed identity of the Diaspora Jew as a "feminised" Other. She describes this as a relationship of contempt towards the previous identity of the Jewish Diaspora viewed as unable to resist anti-semitism and the Holocaust. Lentin argues that Zionism's rejection of this "feminised" identity and its obsession with constructing a nation is reflected in the nature of the symbolism of the movement, which are drawn from modern sources and appropriated as Zionist, instancing the fact that the melody of the Hatikvah anthem drew on the version composed by the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana.[56]

Negation of the life in the Diaspora

Negation of life in the Diaspora is a central assumption in Zionism.[72][73][74][75] Some supporters of Zionism believed that Jews in the Diaspora were prevented from their full growth in Jewish individual and national life.[citation needed]

The rejection of life in the diaspora was not limited to secular Zionism; many religious Zionists shared this opinion, but not all religious Zionism did. Rav Cook, considered one of the most important religious Zionist thinkers, characterized the diaspora as a flawed and alienated existence marked by decline, narrowness, displacement, solitude, and frailty. He believed that the diasporan way of life is diametrically opposed to a "national renaissance," which manifests itself not only in the return to Zion but also in the return to nature and creativity, revival of heroic and aesthetic values, and the resurgence of individual and societal power.[76]

Revival of the Hebrew language

Zionists generally preferred to speak Hebrew, a Semitic language which flourished as a spoken language in the ancient Kingdoms of Israel and Judah during the period from about 1200 to 586 BCE,[78] and continued to be used in some parts of Judea during the Second Temple period and up until 200 CE. It is the language of the Hebrew Bible and the Mishnah, central texts in Judaism. Hebrew was largely preserved throughout later history as the main liturgical language of Judaism.

Zionists worked to modernize Hebrew and adapt it for everyday use. They sometimes refused to speak Yiddish, a language they thought had developed in the context of European persecution. Once they moved to Israel, many Zionists refused to speak their (diasporic) mother tongues and adopted new, Hebrew names. Hebrew was preferred not only for ideological reasons, but also because it allowed all citizens of the new state to have a common language, thus furthering the political and cultural bonds among Zionists.[citation needed]

The revival of the Hebrew language and the establishment of Modern Hebrew is most closely associated with the linguist Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and the Committee of the Hebrew Language (later replaced by the Academy of the Hebrew Language).[79]

In the Israeli Declaration of Independence

Major aspects of the Zionist idea are represented in the Israeli Declaration of Independence:

The Land of Israel was the birthplace of the Jewish people. Here their spiritual, religious and political identity was shaped. Here they first attained to statehood, created cultural values of national and universal significance and gave to the world the eternal Book of Books.

After being forcibly exiled from their land, the people kept faith with it throughout their Dispersion and never ceased to pray and hope for their return to it and for the restoration in it of their political freedom.

Impelled by this historic and traditional attachment, Jews strove in every successive generation to re-establish themselves in their ancient homeland. In recent decades they returned in their masses.[80]

History

Historical and religious background

This section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (November 2023) |

The Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation[81][82] originating from the Israelites[83][84][85] and Hebrews[86][87] of historical Israel and Judah, two Israelite kingdoms that emerged in the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Jews are named after the Kingdom of Judah,[88][89][90] the southern of the two kingdoms, which was centered in Judea with its capital in Jerusalem.[91] The Kingdom of Judah was conquered by Nebuchadnezzar II of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE.[92] The Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem and the First Temple, which was at the center of ancient Judean worship. The Judeans were subsequently exiled to Babylon, in what is regarded as the first Jewish diaspora.[93][94][95]

Seventy years later, after the conquest of Babylon by the Persian Achaemenid Empire, Cyrus the Great allowed the Jews to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple.[96] This event came to be known as the Return to Zion. Under Persian rule, Judah became a self-governing Jewish province. After centuries of Persian and Hellenistic rule, the Jews regained their independence in the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire, which led to the establishment of the Hasmonean Kingdom in Judea. It later expanded over much of modern Israel, and into some parts of Jordan and Lebanon.[97][98][99] The Hasmonean Kingdom became a client state of the Roman Republic in 63 BCE, and in 6 CE, was incorporated into the Roman Empire as the province of Judaea.[100]

During the Great Jewish Revolt (66–73 CE), the Romans destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Second Temple.[101] Of the 600,000 (Tacitus) or 1,000,000 (Josephus) Jews of Jerusalem, all of them either died of starvation, were killed or were sold into slavery.[102] The Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–136 CE) led to the destruction of large parts of Judea, and many Jews were killed, exiled, or sold into slavery. The province of Judaea was renamed Syria Palaestina. These actions are seen by many scholars as an attempt to disconnect the Jewish people from their homeland.[103][104] In the following centuries, many Jews emigrated to thriving centers in the diaspora. Others continued living in the region, especially in the Galilee, the coastal plain, and on the edges of Judea, and some converted.[105][106] By the fourth century CE, the Jews, who had previously constituted the majority of Palestine, had become a minority.[107] A small presence of Jews has been attested for almost all of the period. For example, according to tradition, the Jewish community of Peki'in has maintained a Jewish presence since the Second Temple period.[108][109]

Jewish religious belief holds that the Land of Israel is a God-given inheritance of the Children of Israel based on the Torah, particularly the books of Genesis and Exodus, as well as on the later Prophets.[110][111][112] According to the Book of Genesis, Canaan was first promised to Abraham's descendants; the text is explicit that this is a covenant between God and Abraham for his descendants.[113] The belief that God had assigned Canaan to the Israelites as a Promised Land is also conserved in Christian[114] and Islamic traditions.[115]

Among Jews in the diaspora, the Land of Israel was revered in a cultural, national, ethnic, historical, and religious sense. They thought of a return to it in a future messianic age.[116] The Return to Zion remained a recurring theme among generations, particularly in Passover and Yom Kippur prayers, which traditionally concluded with "Next year in Jerusalem", and in the thrice-daily Amidah (Standing prayer).[117] The biblical prophecy of Kibbutz Galuyot, the ingathering of exiles in the Land of Israel as foretold by the Prophets, became a central idea in Zionism.[118][119][120]

Pre-Zionist initiatives

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (February 2024) |

Pre-Zionist resettlement in Palestine met with various degrees of success. In late antiquity, many Babylonian Jews immigrated to centers of religious study in the Land of Israel.[122] In the 10th century, leaders of the Karaite Jewish community, mostly living under Persian rule, urged their followers to settle in the Land of Israel, where they established their own quarter in Jerusalem.[123]

The number of Jews migrating to the land of Israel rose significantly between the 13th and 19th centuries, mainly due to a general decline in the status of Jews across Europe and an increase in religious persecution, including the expulsion of Jews from England (1290), France (1391), Austria (1421), and Spain (the Alhambra decree of 1492).[124]

In the middle of the 16th century, the Portuguese Sephardi Joseph Nasi, with the support of the Ottoman Empire, tried to gather the Portuguese Jews, first to migrate to Cyprus, then owned by the Republic of Venice, and later to resettle in Tiberias. Nasi—who never converted to Islam[125][126]—eventually obtained the highest medical position in the empire, and actively participated in court life. He convinced Suleiman I to intervene with the Pope on behalf of Ottoman-subject Portuguese Jews imprisoned in Ancona.[125]

In the 17th century Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676) announced himself as the Messiah and gained many Jews to his side, forming a base in Salonika. He first tried to establish a settlement in Gaza, but moved later to Smyrna. After deposing the old rabbi Aaron Lapapa in the spring of 1666, the Jewish community of Avignon, France, prepared to emigrate to the new kingdom.[127]

In the early 19th century, a group of Jews known as the perushim left Lithuania to settle in Ottoman Palestine.

Establishment of the Zionist movement

In the 19th century, a current in Judaism supporting a return to Zion grew in popularity,[128][better source needed] particularly in Europe, where antisemitism and hostility toward Jews were growing. The idea of returning to Palestine was rejected by the conferences of rabbis held in that epoch. Individual efforts supported the emigration of groups of Jews to Palestine, pre-Zionist Aliyah, even before the First Zionist Congress in 1897, the year considered as the start of practical Zionism.[129]

Reform Jews rejected this idea of a return to Zion. The conference of rabbis held at Frankfurt am Main over July 15–28, 1845, deleted from the ritual all prayers for a return to Zion and a restoration of a Jewish state. The Philadelphia Conference, 1869, followed the lead of the German rabbis and decreed that the Messianic hope of Israel is "the union of all the children of God in the confession of the unity of God". In 1885 the Pittsburgh Conference reiterated this interpretation of the Messianic idea of Reform Judaism, expressing in a resolution that "we consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religious community; and we therefore expect neither a return to Palestine, nor a sacrificial worship under the sons of Aaron, nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning a Jewish state".[130]

Jewish settlements were proposed for establishment in the upper Mississippi region by W.D. Robinson in 1819.[131]

Moral but not practical efforts were made in Prague to organize a Jewish emigration, by Abraham Benisch and Moritz Steinschneider in 1835. In the United States, Mordecai Noah attempted to establish a Jewish refuge opposite Buffalo, New York, on Grand Isle, 1825. These early Jewish nation building efforts of Cresson, Benisch, Steinschneider and Noah failed.[132][page needed][133]

Sir Moses Montefiore, famous for his intervention in favor of Jews around the world, including the attempt to rescue Edgardo Mortara, established a colony for Jews in Palestine. In 1854, his friend Judah Touro bequeathed money to fund Jewish residential settlement in Palestine. Montefiore was appointed executor of his will, and used the funds for a variety of projects, including building in 1860 the first Jewish residential settlement and almshouse outside of the old walled city of Jerusalem—today known as Mishkenot Sha'ananim. Laurence Oliphant failed in a like attempt to bring to Palestine the Jewish proletariat of Poland, Lithuania, Romania, and the Turkish Empire (1879 and 1882).

Theodor Herzl and the birth of modern political Zionism

The official beginning of the construction of the New Yishuv in Palestine is usually dated to the arrival of the Bilu group in 1882, who commenced the First Aliyah. In the following years, Jewish immigration to Palestine started in earnest. Most immigrants came from the Russian Empire, escaping the frequent pogroms and state-led persecution in what are now Ukraine and Poland.[citation needed] They founded a number of agricultural settlements with financial support from Jewish philanthropists in Western Europe. Additional Aliyahs followed the Russian Revolution and its eruption of violent pogroms. At the end of the 19th century, Jews were a small minority in Palestine.[134]

In the 1890s, Theodor Herzl (the father of political Zionism) infused Zionism with a new ideology and practical urgency, leading to the First Zionist Congress at Basel in 1897, which created the Zionist Organization (ZO), renamed in 1960 as World Zionist Organization (WZO).[135] In Der Judenstaat, Herzl was explicit in mentioning that the "state of the Jews" could be established only with the support of a European power. He described the Jewish state as an "outpost of civilization against Barbarism". In separate writing, Herzl compared himself to Cecil Rhodes, who was a strong supporter of British colonialist and imperialist ideologies.[56]: 327 [better source needed]

In 1896, Theodor Herzl expressed in Der Judenstaat his views on "the restoration of the Jewish state".[136] Herzl considered antisemitism to be an eternal feature of all societies in which Jews lived as minorities, and that only a sovereignty could allow Jews to escape eternal persecution: "Let them give us sovereignty over a piece of the Earth's surface, just sufficient for the needs of our people, then we will do the rest!" he proclaimed exposing his plan.[137]: 27, 29

Success and stumbles in Russia

Before World War I, although led by Austrian and German Jews, Zionism was primarily composed of Russian Jews.[138] Initially, Zionists were a minority, both in Russia and worldwide.[139][140][141][142] Russian Zionism quickly became a major force within the movement, making up about half the delegates at Zionist Congresses.[143]

Despite its success in attracting followers, Russian Zionism faced fierce opposition from the Russian intelligentsia across the political spectrum and socioeconomic classes. It was condemned by different groups as reactionary, messianic, and unrealistic, arguing that it would isolate Jews and exacerbate their circumstances rather than integrate them into European societies.[143] Religious Jews such as Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum viewed in Zionism a desecration of their sacred beliefs and a Satanic plot, while others hardly thought it deserved serious attention.[144] For them, Zionism was seen as an attempt to defy the divine order to await the coming of the Messiah.[145] However, many of these religious Jews still believed in the Messiah coming soon. For example, Rabbi Israel Meir Kahan "was so convinced of the imminent arrival of the Messiah that he urged his students to study the laws of the priesthood so that the priests would be prepared to carry out their duties when the Temple in Jerusalem was rebuilt."[144]

Criticism was not limited to religious Jews. Bundist socialists and liberals of the Voskhod newspaper attacked Zionism for distracting from class struggle and blocking the path to Jewish emancipation in Russia, respectively.[143] Figures like historian Simon Dubnow saw potential value in Zionism promoting Jewish identity but fundamentally rejected a Jewish state as messianic and unfeasible.[146] They provided alternative emancipatory solutions, such as assimilation, emigration, and Diaspora nationalism.[147] The opposition to Zionism, rooted in the intelligentsia's rationalist worldview, weakened its appeal among potential adherents like the Jewish working class and intelligentsia.[143] Ultimately, the Russian intelligentsia was united in the view that Zionism was an aberrant ideology that ran counter to their beliefs in Jewish assimilation.

Pre-state institutions

- Zionist Organization (ZO), est. 1897

- Zionist Congress (est. 1897), the supreme organ of the ZO

- Palestine Office (est. 1908), the executive arm of the ZO in Palestine

- Jewish National Fund (JNF), est. 1901 to buy and develop land in Palestine

- Keren Hayesod, est. 1920 to collect funds

- Jewish Agency, est. 1929 as the worldwide operative branch of the ZO

Funding

The Zionist enterprise was mainly funded by major benefactors who made large contributions, sympathisers from Jewish communities across the world (see for instance the Jewish National Fund's collection boxes), and the settlers themselves. The movement established a bank for administering its finances, the Jewish Colonial Trust (est. 1888, incorporated in London in 1899). A local subsidiary was formed in 1902 in Palestine, the Anglo-Palestine Bank.

A list of pre-state large contributors to Pre-Zionist and Zionist enterprises would include, alphabetically,

- Isaac Leib Goldberg (1860–1935), Zionist leader and philanthropist from Russia

- Maurice de Hirsch (1831–1896), German Jewish financier and philanthropist, founder of the Jewish Colonization Association

- Moses Montefiore (1784–1885), British Jewish banker and philanthropist in Britain and the Levant, initiator and financier of Proto-Zionism

- Edmond James de Rothschild (1845–1934), French Jewish banker and major donor of the Zionist project

Pre-state paramilitary organizations

A list of Jewish pre-state paramilitary and defense organisations in Palestine would include:

- Direct precursors of the IDF

Not sanctioned by central Zionist administration

- Unrelated

- Mahane Yehuda, 'Judah's Camp', a mounted guards company founded by Michael Halperin in 1891[148] (see Ness Ziona)

- HaNoter, 'The Guard' (1912–1913),[149] distinct from the British Mandate-period Notrim[150]

- HaMagen, 'The Shield' (1915–1917)[150]

Territories considered

Throughout the first decade of the Zionist movement, there were several instances where some Zionist figures, including Herzl, supported a Jewish state in places outside Palestine, such as "Uganda" (actually parts of British East Africa today in Kenya), Argentina, Cyprus, Mesopotamia, Mozambique, and the Sinai Peninsula.[21] Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, was initially content with any Jewish self-governed state.[151] Jewish settlement of Argentina was the project of Maurice de Hirsch.[152] It is unclear if Herzl seriously considered this alternative plan,[153] however he later reaffirmed that Palestine would have greater attraction because of the historic ties of Jews with that area.[137]

A major concern and driving reason for considering other territories was the Russian pogroms, in particular the Kishinev massacre, and the resulting need for quick resettlement in a safer place.[154] However, other Zionists emphasized the memory, emotion and tradition linking Jews to the Land of Israel.[155] Zion became the name of the movement, after the place where King David established his kingdom, following his conquest of the Jebusite fortress there (2 Samuel 5:7, 1 Kings 8:1). The name Zion was synonymous with Jerusalem. Palestine only became Herzl's main focus after his Zionist manifesto 'Der Judenstaat' was published in 1896, but even then he was hesitant to focus efforts solely on resettlement in Palestine when speed was of the essence.[156]

In 1903, British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain offered Herzl 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2) in the Uganda Protectorate for Jewish settlement in Great Britain's East African colonies.[157] Herzl accepted to evaluate Joseph Chamberlain's proposal,[158]: 55–56 and it was introduced the same year to the World Zionist Organization's Congress at its sixth meeting, where a fierce debate ensued. Some groups felt that accepting the scheme would make it more difficult to establish a Jewish state in Palestine, the African land was described as an "ante-chamber to the Holy Land". It was decided to send a commission to investigate the proposed land by 295 to 177 votes, with 132 abstaining. The following year, Congress sent a delegation to inspect the plateau. A temperate climate due to its high elevation, was thought to be suitable for European settlement. However, the area was populated by a large number of Maasai, who did not seem to favour an influx of Europeans. Furthermore, the delegation found it to be filled with lions and other animals.

After Herzl died in 1904, the Congress decided on the fourth day of its seventh session in July 1905 to decline the British offer and, according to Adam Rovner, "direct all future settlement efforts solely to Palestine".[157][159] Israel Zangwill's Jewish Territorialist Organization aimed for a Jewish state anywhere, having been established in 1903 in response to the Uganda Scheme. It was supported by a number of the Congress's delegates. Following the vote, which had been proposed by Max Nordau, Zangwill charged Nordau that he "will be charged before the bar of history," and his supporters blamed the Russian voting bloc of Menachem Ussishkin for the outcome of the vote.[159]

The subsequent departure of the JTO from the Zionist Organization had little impact.[157][160][161] The Zionist Socialist Workers Party was also an organization that favored the idea of a Jewish territorial autonomy outside of Palestine.[162]

As an alternative to Zionism, Soviet (USSR) authorities established a Jewish Autonomous Oblast in 1934, which remains extant as the only autonomous oblast of Russia.[163]

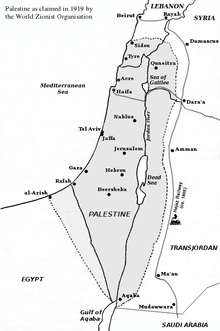

According to Elaine Hagopian, in the early decades it foresaw the homeland of the Jews as extending not only over the region of Palestine, but into Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt, with its borders more or less coinciding with the major riverine and water-rich areas of the Levant.[164]

Balfour Declaration and the Mandate for Palestine

Lobbying by Russian Jewish immigrant Chaim Weizmann, together with fear that American Jews would encourage the US to support Germany in the war against Russia, culminated in the British government's Balfour Declaration of 1917.

It endorsed the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, as follows:

His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.[165]

In 1922, the League of Nations adopted the declaration, and granted to Britain the Palestine Mandate:

The Mandate will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home ... and the development of self-governing institutions, and also safeguard the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion.[166]

Weizmann's role in obtaining the Balfour Declaration led to his election as the Zionist movement's leader. He remained in that role until 1948, and then was elected as the first President of Israel after the nation gained independence.

A number of high-level representatives of the international Jewish women's community participated in the First World Congress of Jewish Women, which was held in Vienna, Austria, in May 1923. One of the main resolutions was: "It appears ... to be the duty of all Jews to co-operate in the social-economic reconstruction of Palestine and to assist in the settlement of Jews in that country."[167]

In 1927, Ukrainian Jew Yitzhak Lamdan wrote an epic poem titled Masada to reflect the plight of the Jews, calling for a "last stand".[168]

Nazism and the Holocaust

In 1933, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, and in 1935 the Nuremberg Laws made German Jews (and later Austrian and Czech Jews) stateless refugees. Similar rules were applied by the many Nazi allies in Europe. The subsequent growth in Jewish migration fostered the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. Britain established the Peel Commission to investigate the situation. The commission called for a two-state solution and compulsory transfer of populations. The Arabs opposed the partition plan and Britain later rejected this solution and instead implemented the White Paper of 1939. This planned to end Jewish immigration by 1944 and to allow no more than 75,000 additional Jewish migrants. At the end of the five-year period in 1944, only 51,000 of the 75,000 immigration certificates provided for had been utilized, and the British offered to allow immigration to continue beyond cutoff date of 1944, at a rate of 1500 per month, until the remaining quota was filled.[169][170] According to Arieh Kochavi, at the end of the war, the Mandatory Government had 10,938 certificates remaining and gives more details about government policy at the time.[169] The British maintained the policies of the 1939 White Paper until the end of the Mandate.[171]

| Year | Muslims | Jews | Christians | Others | Total Settled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1922 | 486,177 (74.9%) | 83,790 (12.9%) | 71,464 (11.0%) | 7,617 (1.2%) | 649,048 |

| 1931 | 693,147 (71.7%) | 174,606 (18.1%) | 88,907 (9.2%) | 10,101 (1.0%) | 966,761 |

| 1941 | 906,551 (59.7%) | 474,102 (31.2%) | 125,413 (8.3%) | 12,881 (0.8%) | 1,518,947 |

| 1946 | 1,076,783 (58.3%) | 608,225 (33.0%) | 145,063 (7.9%) | 15,488 (0.8%) | 1,845,559 |

The growth of the Jewish community in Palestine and the devastation of European Jewish life sidelined the World Zionist Organization (WZO). The Jewish Agency for Palestine under the leadership of David Ben-Gurion increasingly dictated policy with support from American Zionists who provided funding and influence in Washington, D.C., including via the American Palestine Committee.[citation needed] In 1938, Ben-Gurion argued that a significant source of fear for Zionists was the defensive political strength of the Palestinian position, stating:[173]

A people which fights against the usurpation of its land will not tire so easily. ... When we say that the Arabs are the aggressors and we defend ourselves — this is only half the truth. ... olitically we are the aggressors and they defend themselves. The country is theirs, because they inhabit it, whereas we want to come here and settle down, and in their view we want to take away from them their country.

During World War II, as the horrors of the Holocaust became known, the Zionist leadership formulated the One Million Plan, a reduction from Ben-Gurion's previous target of two million immigrants. Following the end of the war, many stateless refugees, mainly Holocaust survivors, began migrating to Palestine in small boats in defiance of British rules. The Holocaust united much of the rest of world Jewry behind the Zionist project.[174] The British either imprisoned these Jews in Cyprus or sent them to the British-controlled Allied Occupation Zones in Germany. The British, having faced Arab revolts, were now facing opposition by Zionist groups in Palestine for subsequent restrictions on Jewish immigration. In January 1946 the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry, a joint British and American committee, was tasked to examine political, economic and social conditions in Mandatory Palestine and the well-being of the peoples now living there; to consult representatives of Arabs and Jews, and to make other recommendations 'as necessary' for an interim handling of these problems as well as for their eventual solution.[175] Following the failure of the 1946–47 London Conference on Palestine, at which the United States refused to support the British leading to both the Morrison–Grady Plan and the Bevin Plan being rejected by all parties, the British decided to refer the question to the UN on February 14, 1947.[176][fn 2]

Post-World War II

With the German invasion of the USSR in 1941, Stalin reversed his long-standing opposition to Zionism, and tried to mobilize worldwide Jewish support for the Soviet war effort. A Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was set up in Moscow. Many thousands of Jewish refugees fled the Nazis and entered the Soviet Union during the war, where they reinvigorated Jewish religious activities and opened new synagogues.[177] In May 1947 Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko told the United Nations that the USSR supported the partition of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. The USSR formally voted that way in the UN in November 1947.[178] However once Israel was established, Stalin reversed positions, favoured the Arabs, arrested the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, and launched attacks on Jews in the USSR.[179]

In 1947, the UN Special Committee on Palestine recommended that western Palestine should be partitioned into a Jewish state, an Arab state and a UN-controlled territory, Corpus separatum, around Jerusalem.[180] This partition plan was adopted on November 29, 1947, with UN GA Resolution 181, 33 votes in favor, 13 against, and 10 abstentions. The vote led to celebrations in Jewish communities and protests in Arab communities throughout Palestine.[181] Violence throughout the country, previously an Arab and Jewish insurgency against the British, Jewish-Arab communal violence, spiralled into the 1947–1949 Palestine war. According to various assessments of the UN, the conflict led to an exodus of 711,000 to 957,000 Palestinian Arabs,[182] outside of Israel's territories. More than a quarter had already fled during the 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine, before the Israeli Declaration of Independence and the outbreak of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. After the 1949 Armistice Agreements, a series of laws passed by the first Israeli government prevented displaced Palestinians from claiming private property or returning on the state's territories. They and many of their descendants remain refugees supported by UNRWA.[183][184]

Since the creation of the State of Israel, the World Zionist Organization has functioned mainly as an organization dedicated to assisting and encouraging Jews to migrate to Israel. It has provided political support for Israel in other countries but plays little role in internal Israeli politics. The movement's major success since 1948 was in providing logistical support for Jewish migrants and refugees and, most importantly, in assisting Soviet Jews in their struggle with the authorities over the right to leave the USSR and to practice their religion in freedom, and the exodus of 850,000 Jews from the Arab world, mostly to Israel. In 1944–45, Ben-Gurion described the One Million Plan to foreign officials as being the "primary goal and top priority of the Zionist movement."[185] The immigration restrictions of the British White Paper of 1939 meant that such a plan could not be put into large scale effect until the Israeli Declaration of Independence in May 1948. The new country's immigration policy had some opposition within the new Israeli government, such as those who argued that there was "no justification for organizing large-scale emigration among Jews whose lives were not in danger, particularly when the desire and motivation were not their own"[186] as well as those who argued that the absorption process caused "undue hardship".[187] However, the force of Ben-Gurion's influence and insistence ensured that his immigration policy was carried out.[188][189]

Role in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict

The arrival of Zionist settlers to Palestine in the late 19th century is widely seen as the start of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[56]: 70 [190][191] In response to Ben-Gurion's 1938 quote that "politically we are the aggressors and they defend themselves", Israeli historian Benny Morris says, "Ben-Gurion, of course, was right. Zionism was a colonizing and expansionist ideology and movement", and that "Zionist ideology and practice were necessarily and elementally expansionist." Morris describes the Zionist goal of establishing a Jewish state in Palestine as necessarily displacing and dispossessing the Arab population.[192] The practical issue of establishing a Jewish state in a majority non-Jewish and Arab region was a fundamental issue for the Zionist movement.[192] Zionists used the term "transfer" as a euphemism for the removal, or ethnic cleansing, of the Arab Palestinian population.[fn 3][193] According to Benny Morris, "the idea of transferring the Arabs out... was seen as the chief means of assuring the stability of the 'Jewishness' of the proposed Jewish State".[192] Nur Masalha writes that:

It should not be imagined that the concept of transfer was held only by maximalists or extremists within the Zionist movement. On the contrary, it was embraced by almost all shades of opinion, from the Revisionist right to the Labor left. Virtually every member of the Zionist pantheon of founding fathers and important leaders supported it and advocated it in one form or another, from Chaim Weizmann and Vladimir Jabotinsky to David Ben-Gurion and Menahem Ussishkin. Supporters of transfer included such moderates as the “Arab appeaser" Moshe Shertok and the socialist Arthur Ruppin, founder of Brit Shalom, a movement advocating equal rights for Arabs and Jews. More importantly, transfer proposals were put forward by the Jewish Agency itself, in effect the government of the Yishuv.[fn 4]

According to Morris, the idea of ethnically cleansing the land of Palestine was to play a large role in Zionist ideology from the inception of the movement. He explains that "transfer" was "inevitable and inbuilt into Zionism" and that a land which was primarily Arab could not be transformed into a Jewish state without displacing the Arab population.[fn 5] Further, the stability of the Jewish state could not be ensured given the Arab population's fear of displacement. He explains that this would be the primary source of conflict between the Zionist movement and the Arab population.[193]

Types

| Country/Region | Members | Delegates |

|---|---|---|

| Poland | 299,165 | 109 |

| US | 263,741 | 114 |

| Palestine | 167,562 | 134 |

| Romania | 60,013 | 28 |

| United Kingdom | 23,513 | 15 |

| South Africa | 22,343 | 14 |

| Canada | 15,220 | 8 |

The multi-national, worldwide Zionist movement is structured on representative democratic principles. Congresses are held every four years (they were held every two years before the Second World War) and delegates to the congress are elected by the membership. Members are required to pay dues known as a shekel. At the congress, delegates elect a 30-man executive council, which in turn elects the movement's leader. The movement was democratic from its inception and women had the right to vote.[195]

Until 1917, the World Zionist Organization pursued a strategy of building a Jewish National Home through persistent small-scale immigration and the founding of such bodies as the Jewish National Fund (1901 – a charity that bought land for Jewish settlement) and the Anglo-Palestine Bank (1903 – provided loans for Jewish businesses and farmers). In 1942, at the Biltmore Conference, the movement included for the first time an express objective of the establishment of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel.[196]

The 28th Zionist Congress, meeting in Jerusalem in 1968, adopted the five points of the "Jerusalem Program" as the aims of Zionism today. They are:[197]

- Unity of the Jewish People and the centrality of Israel in Jewish life

- Ingathering of the Jewish People in its historic homeland, Eretz Israel, through Aliyah from all countries

- Strengthening of the State of Israel, based on the prophetic vision of justice and peace

- Preservation of the identity of the Jewish People through fostering of Jewish and Hebrew education, and of Jewish spiritual and cultural values

- Protection of Jewish rights everywhere

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk