A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| |

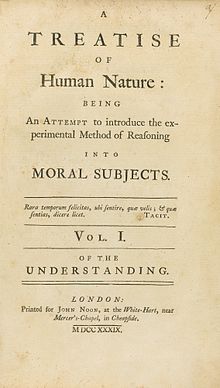

| Author | David Hume |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Philosophy |

Publication date | 1739–40 |

| Pages | 368 |

| ISBN | 0-7607-7172-3 |

| Text | A Treatise of Human Nature at Wikisource |

A Treatise of Human Nature: Being an Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects (1739–40) is a book by Scottish philosopher David Hume, considered by many to be Hume's most important work and one of the most influential works in the history of philosophy.[1] The Treatise is a classic statement of philosophical empiricism, scepticism, and naturalism. In the introduction Hume presents the idea of placing all science and philosophy on a novel foundation: namely, an empirical investigation into human nature. Impressed by Isaac Newton's achievements in the physical sciences, Hume sought to introduce the same experimental method of reasoning into the study of human psychology, with the aim of discovering the "extent and force of human understanding". Against the philosophical rationalists, Hume argues that the passions, rather than reason, cause human behaviour. He introduces the famous problem of induction, arguing that inductive reasoning and our beliefs regarding cause and effect cannot be justified by reason; instead, our faith in induction and causation is caused by mental habit and custom. Hume defends a sentimentalist account of morality, arguing that ethics is based on sentiment and the passions rather than reason, and famously declaring that "reason is, and ought only to be the slave to the passions". Hume also offers a sceptical theory of personal identity and a compatibilist account of free will.

Isaiah Berlin wrote of Hume that "no man has influenced the history of philosophy to a deeper or more disturbing degree".[2] Jerry Fodor wrote of Hume's Treatise that it is "the foundational document of cognitive science".[3] However, the public in Britain at the time did not agree, nor in the end did Hume himself agree, reworking the material in both An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748) and An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (1751). In the Author's introduction to the former, Hume wrote:

Most of the principles, and reasonings, contained in this volume, were published in a work in three volumes, called A Treatise of Human Nature: a work which the Author had projected before he left College, and which he wrote and published not long after. But not finding it successful, he was sensible of his error in going to the press too early, and he cast the whole anew in the following pieces, where some negligences in his former reasoning and more in the expression, are, he hopes, corrected. Yet several writers who have honoured the Author's Philosophy with answers, have taken care to direct all their batteries against that juvenile work, which the author never acknowledged, and have affected to triumph in any advantages, which, they imagined, they had obtained over it: A practice very contrary to all rules of candour and fair-dealing, and a strong instance of those polemical artifices which a bigotted zeal thinks itself authorized to employ. Henceforth, the Author desires, that the following Pieces may alone be regarded as containing his philosophical sentiments and principles.

Regarding An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, Hume said: "of all my writings, historical, philosophical, or literary, incomparably the best".[4]

Content

Introduction

Hume's introduction presents the idea of placing all science and philosophy on a novel foundation: namely, an empirical investigation into human psychology. He begins by acknowledging "that common prejudice against metaphysical reasonings ", a prejudice formed in reaction to "the present imperfect condition of the sciences" (including the endless scholarly disputes and the inordinate influence of "eloquence" over reason). But since the truth "must lie very deep and abstruse" where "the greatest geniuses" have not found it, careful reasoning is still needed. All sciences, Hume continues, ultimately depend on "the science of man": knowledge of "the extent and force of human understanding,... the nature of the ideas we employ, and... the operations we perform in our reasonings" is needed to make real intellectual progress. So Hume hopes "to explain the principles of human nature", thereby "propos a compleat system of the sciences, built on a foundation almost entirely new, and the only one upon which they can stand with any security". But an a priori psychology would be hopeless: the science of man must be pursued by the experimental methods of the natural sciences. This means we must rest content with well-confirmed empirical generalisations, forever ignorant of "the ultimate original qualities of human nature". And in the absence of controlled experiments, we are left to "glean up our experiments in this science from a cautious observation of human life, and take them as they appear in the common course of the world, by men's behaviour in company, in affairs, and in their pleasures".

Book 1: Of the Understanding

Part 1: Of ideas, their origin, composition, connexion, abstraction, etc.

Hume begins by arguing that each simple idea is derived from a simple impression so that all our ideas are ultimately derived from experience: thus Hume accepts concept empiricism and rejects the purely intellectual and innate ideas found in rationalist philosophy. Hume's doctrine draws on two important distinctions: between impressions (the forceful perceptions found in experience, "all our sensations, passions and emotions") and ideas (the faint perceptions found in "thinking and reasoning"), and between complex perceptions (which can be distinguished into simpler parts) and simple perceptions (which cannot). Our complex ideas, he acknowledges, may not directly correspond to anything in experience (e.g., we can form the complex idea of a heavenly city). But each simple idea (e.g., of the colour red) directly corresponds to a simple impression resembling it—and this regular correspondence suggests that the two are causally connected. Since the simple impressions come before the simple ideas, and since those without functioning senses (e.g., blindness) end up lacking the corresponding ideas, Hume concludes that simple ideas must be derived from simple impressions. Notoriously, Hume considers and dismisses the 'missing shade of blue' counterexample.

| Perceptions in Treatise 1.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| In Part 1 of Book 1, Hume divides mental perceptions into different categories. The simple/complex distinction, which may apply to perceptions in all categories, is not pictured. |

Briefly examining impressions, Hume then distinguishes between impressions of sensation (found in sense experience) and impressions of reflection (found mainly in emotional experience), only to set aside any further discussion for Book 2's treatment of the passions. Returning to ideas, Hume finds two key differences between ideas of the memory and ideas of the imagination: the former are more forceful than the latter, and whereas the memory preserves the "order and position" of the original impressions, the imagination is free to separate and rearrange all simple ideas into new complex ideas. But despite this freedom, the imagination still tends to follow general psychological principles as it moves from one idea to another: this is the "association of ideas". Here Hume finds three "natural relations" guiding the imagination: resemblance, contiguity, and causation. But the imagination remains free to compare ideas along any of seven "philosophical relations": resemblance, identity, space/time, quantity/number, quality/degree, contrariety, and causation. Hume finishes this discussion of complex ideas with a sceptical account of our ideas of substances and modes: though both are nothing more than collections of simple ideas associated together by the imagination, the idea of a substance also involves attributing either a fabricated "unknown something, in which are supposed to inhere" or else some relations of contiguity or causation binding the qualities together and fitting them to receive new qualities should any be discovered.

Hume finishes Part 1 by arguing (following Berkeley) that so-called "abstract ideas" are in fact only particular ideas used in a general way. First, he makes a three-point case against indeterminate ideas of quantity or quality, insisting on the impossibility of differentiating or distinguishing a line's length from the line itself, the ultimate derivation of all ideas from fully determinate impressions, and the impossibility of indeterminate objects in reality and hence in idea as well. Second, he gives a positive account of how abstract thought actually works: once we are accustomed to use the same term for a number of resembling items, hearing this general term will call up some particular idea and activate the associated custom, which disposes the imagination to call up any resembling particular ideas as needed. Thus the general term "triangle" both calls up an idea of some particular triangle and activates the custom disposing the imagination to call up any other ideas of particular triangles. Finally, Hume uses this account to explain so-called "distinctions of reason" (e.g., distinguishing the motion of a body from the body itself). Though such distinctions are strictly impossible, Hume argues, we achieve the same effect by noting the various points of resemblance between different objects.

Part 2: Of the ideas of space and time

Hume's "system concerning space and time" features two main doctrines: the finitist doctrine that space and time are not infinitely divisible, and the relationist doctrine that space and time cannot be conceived apart from objects. Hume begins by arguing that, since "the capacity of the mind is limited", our imagination and senses must eventually reach a minimum: ideas and impressions so minute as to be indivisible. And since nothing can be more minute, our indivisible ideas are "adequate representations of the most minute parts of extension". Upon consideration of these "clear ideas", Hume presents a few arguments to demonstrate that space and time are not infinitely divisible, but are instead composed of indivisible points. On his account, the idea of space is abstracted from our sense experience (arrangements of coloured or tangible points), and the idea of time from the changing succession of our own perceptions. And this means that space and time cannot be conceived on their own, apart from objects arranged in space or changing across time. Thus we have no idea of absolute space and time, so that vacuums and time without change are ruled out.

Hume then defends his two doctrines against objections. In defending his finitism against mathematical objections, he argues that the definitions of geometry support his account. He then argues that since important geometric ideas (equality, straightness, flatness) do not have any precise and workable standard beyond common observation, corrective measurements, and the "imaginary" standards we are naturally prone to fabricate, it follows that the extremely subtle geometric demonstrations of infinite divisibility cannot be trusted. Next, Hume defends his relationist doctrine, critically examining the alleged idea of a vacuum. No such idea can be derived from our experience of darkness or motion (alone or accompanied by visible or tangible objects), but it is indeed this experience that explains why we mistakenly think we have the idea: according to Hume, we confuse the idea of two distant objects separated by other visible or tangible objects with the very similar idea of two objects separated by an invisible and intangible distance. With this diagnosis in hand, he replies to three objections from the vacuist camp—adding on a sceptical note that his "intention never was to penetrate into the nature of bodies, or explain the secret causes of their operations", but only "to explain the nature and causes of our perceptions, or impressions and ideas".

In the final section, Hume accounts for our ideas of existence and of external existence. First, he argues that there is no distinct impression from which to derive the idea of existence. Instead, this idea is nothing more than the idea of any object, so that thinking of something and thinking of it as existent is the very same thing. Next, he argues that we cannot conceive of anything beyond our own perceptions; thus our conception of the existence of external objects is at most a "relative idea".

Part 3: Of knowledge and probability

Sections 1–3

Hume recalls the seven philosophical relations, and divides them into two classes: four which can give us "knowledge and certainty", and three which cannot. (This division reappears in Hume's first Enquiry as "relations of ideas" and "matters of fact", respectively.) As for the four relations, he notes, all can yield knowledge by way of intuition: immediate recognition of a relation (e.g., one idea as brighter in colour than another). But with one of the four, "proportions in quantity or number", we commonly achieve knowledge by way of demonstration: step-by-step inferential reasoning (e.g., proofs in geometry). Hume makes two remarks on demonstrative reasoning in mathematics: that geometry is not as precise as algebra (though still generally reliable), and that mathematical ideas are not "spiritual and refin'd perceptions", but instead copied from impressions.

| Immediate | Inferential | |

|---|---|---|

| Relations of ideas | intuition | demonstrative reasoning |

| Matters of fact | perception | probable reasoning |

As for the other three relations, two of them (identity and space/time) are simply a matter of immediate sensory perception (e.g., one object next to another). But with the last relation, causation, we can go beyond the senses, by way of a form of inferential reasoning he calls probable reasoning. Here Hume embarks on his celebrated examination of causation, beginning with the question From what impression do we derive our idea of causation? All that can be observed in a single instance of cause and effect are two relations: contiguity in space, and priority in time. But Hume insists that our idea of causation also includes a mysterious necessary connection linking cause to effect. "topt short" by this problem, Hume puts the idea of necessary connection on hold and examines two related questions: Why do we accept the maxim 'whatever begins to exist must have a cause'?, and How does the psychological process of probable reasoning work? Addressing the first question, Hume argues that the maxim is not founded on intuition or demonstration (contending that we can at least conceive of objects beginning to exist without a cause), and then rebuts four alleged demonstrations of the maxim. He concludes that our acceptance of this maxim must be somehow drawn "from observation and experience", and thus turns to the second question.

Sections 4–8

Hume develops a detailed three-stage psychological account of how probable reasoning works (i.e., how "the judgement" operates). First, our senses or memory must present us with some object: our confidence in this perception (our "assent") is simply a matter of its force and vivacity. Second, we must make an inference, moving from our perception of this object to an idea of another object: since the two objects are perfectly distinct from each other, this inference must draw on past experience of the two objects being observed together again and again. (This "constant conjunction" is promptly filed alongside contiguity and priority, in Hume's still-developing account of our idea of causation.) But what exactly is the process by which we draw on past experience and make an inference from the present object to the other object?

Here the famous "problem of induction" arises. Hume argues that this all-important inference cannot be accounted for by any process of reasoning: neither demonstrative reasoning nor probable reasoning. Not demonstrative reasoning: it cannot be demonstrated that the future will resemble the past, for "e can at least conceive a change in the course of nature", in which the future significantly differs from the past. And not probable reasoning: that kind of reasoning itself draws on past experience, which means it presupposes that the future will resemble the past. In other words, in explaining how we draw on past experience to make causal inferences, we cannot appeal to a kind of reasoning that itself draws on past experience—that would be a vicious circle that gets us nowhere.

The inference is not based on reasoning, Hume concludes, but on the association of ideas: our innate psychological tendency to move along the three "natural relations". Recall that one of the three is causation: thus when two objects are constantly conjoined in our experience, observing the one naturally leads us to form an idea of the other. This brings us to the third and final stage of Hume's account, our belief in the other object as we conclude the process of probable reasoning (e.g., seeing wolf tracks and concluding confidently that they were caused by wolves). On his account of belief, the only difference between a believed idea and a merely conceived idea lies in the belief's additional force and vivacity. And there is a general psychological tendency for any lively perception to transfer some of its force and vivacity to any other perception naturally related to it (e.g., seeing "the picture of an absent friend" makes our idea of the friend more lively, by the natural relation of resemblance). Thus in probable reasoning, on Hume's account, our lively perception of the one object not only leads us to form a mere idea of the other object, but enlivens that idea into a full-fledged belief. (This is only the simplest case: Hume also intends his account to explain probable reasoning without conscious reflection as well as probable reasoning based on only one observation.)

Sections 9–13

Hume now pauses for a more general examination of the psychology of belief. The other two natural relations (resemblance and contiguity) are too "feeble and uncertain" to bring about belief on their own, but they can still have a significant influence: their presence strengthens our preexisting convictions, they bias us in favor of causes that resemble their effects, and their absence explains why so many don't "really believe" in an afterlife. Similarly, other kinds of custom-based conditioning (e.g., rote learning, repeated lying) can induce strong beliefs. Next, Hume considers the mutual influence of reasoning and the passions, and of belief and the imagination. Only beliefs can have motivational influence: it is the additional force and vivacity of a belief (as opposed to a mere idea) that makes it "able to operate on the will and passions". And in turn we tend to favor beliefs that flatter our passions. Likewise, a story must be somewhat realistic or familiar to please the imagination, and an overactive imagination can result in delusional belief. Hume sees these diverse phenomena as confirming his "force and vivacity" account of belief. Indeed, we keep ourselves "from augmenting our belief upon every increase of the force and vivacity of our ideas" only by soberly reflecting on past experience and forming "general rules" for ourselves.

| Probable reasoning in Treatise 1.3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| In Part 3 of Book 1, Hume divides probable reasoning into different categories. |

Hume then examines probable reasoning under conditions of empirical uncertainty, distinguishing "proofs" (conclusive empirical evidence) from mere "probabilities" (less than conclusive empirical evidence). Beginning with a brief section on the "probability of chances", he gives the example of a six-sided die, four sides marked one way and two sides marked another way: background causes lead us to expect the die to land with a side facing up, but the force of this expectation is divided indifferently across the six sides, and finally reunited according to the die's markings, so that we end up expecting the one marking more than the other. This is mainly prelude to the "probability of causes", where Hume distinguishes three "species of probability": (1) "imperfect experience", where young children have not observed enough to form any expectations, (2) "contrary causes", where the same event has been observed to have different causes and effects in different circumstances, due to hidden factors, and (3) analogy, where we rely on a history of observations that only imperfectly resemble the present case. He focuses on the second species of probability (specifically reflective reasoning about a mixed body of observations), offering a psychological explanation much like that of the probability of chances: we begin with the custom-based impulse to expect that the future will resemble the past, divide it across the particular past observations, and then (reflecting on these observations) reunite the impulses of any matching observations, so that the final balance of belief favors the most frequently observed type of case.

Hume's discussion of probability finishes with a section on common cognitive biases, starting with recency effects. First, the more recent the event whose cause or effect we are looking for, the stronger our belief in the conclusion. Second, the more recent the observations we draw on, the stronger our belief in the conclusion. Third, the longer and more discontinuous a line of reasoning, the weaker our belief in the conclusion. Fourth, irrational prejudices can be formed by overgeneralizing from experience: the imagination is unduly influenced by any "superfluous circumstances" that have frequently been observed to accompany the circumstances that actually matter. And paradoxically, the only way to correct for the pernicious influence of "general rules" is to follow other general rules, formed by reflecting on the circumstances of the case and our cognitive limitations. Throughout the section, Hume uses his "force and vivacity" account of belief to account for these "unphilosophical" influences on our reasoning.

Sections 14–16

Having completed his account of probable reasoning, Hume returns to the mysterious idea of necessary connection. He rejects some proposed sources of this idea: not from the "known qualities of matter", nor from God, nor from some "unknown quality" of matter, nor from our power to move our body at will. For all ideas derive from experience, and in no single case do we observe anything like a necessary connection linking cause to effect. But the idea does arise upon repeated observations, and since mere repetition cannot produce anything new in the objects themselves, the idea must therefore derive from something new in our mind. Thus he concludes that the idea of necessary connection is derived from inside: from the feeling we experience when the mind (conditioned by repeated observation) makes a causal inference. And though his conclusion is shocking to common sense, Hume explains it away by noting that "the mind has a great propensity to spread itself on external objects". Finally, he offers two definitions of "cause": one in terms of the objects (viz. their relations of priority, contiguity, and constant conjunction), and another in terms of the mind (viz. the causal inference it makes upon observing the objects).

Hume finishes Part 3 with two brief sections. First, he presents eight rules for empirically identifying true causes: after all, if we leave aside experience, "ny thing may produce any thing". Second, he compares human reason with animal reason, a comparison which clinches the case for his associationist account of probable reasoning: after all, animals are clearly capable of learning from experience through conditioning, and yet they are clearly incapable of any sophisticated reasoning.

Part 4: Of the sceptical and other systems of philosophy

Sections 1–2

Hume begins Part 4 by arguing that "all knowledge degenerates into probability", due to the possibility of error: even the rock solid certainty of mathematics becomes less than certain when we remember that we might have made a mistake somewhere. But things get worse: reflection on the fallibility of our mind, and meta-reflection on the fallibility of this first reflection, and so on ad infinitum, ultimately reduces probability into total scepticism—or at least it would, if our beliefs were governed by the understanding alone. But according to Hume, this "extinction of belief" does not actually happen: having beliefs is part of human nature, which only confirms Hume's account of belief as "more properly an act of the sensitive, than of the cogitative part of our natures". And as for why we do not sink into total scepticism, Hume argues that the mind has a limited quantity of "force and activity", and that difficult and abstruse reasoning "strain the imagination", "hinder the regular flowing of the passions and sentiments". As a result, extremely subtle sceptical argumentation is unable to overpower and destroy our beliefs.

Next comes an extremely lengthy account of why we believe in an external physical world: i.e., why we think objects have a continued (existing when unobserved) and distinct (existing external to and independent of the mind) existence. Hume considers three potential sources of this belief—the senses, reason, and the imagination. It's not the senses: clearly they are incapable of informing us of anything existing unobserved. Nor can they inform us of objects with distinct existence: the senses present us with sense perceptions only, which means they cannot present them as representations of some further objects, nor present them as themselves objects with distinct existence (for the senses are unable to identify the mysterious self, distinguishing it from and comparing it with sense perceptions). And it's not reason: even children and fools believe in an external world, and nearly all of us naïvely take our perceptions to be objects with a continued and distinct existence, which goes against reason. So this belief must come from the imagination.

But only some of our impressions bring about the belief: namely, impressions with constancy (invariableness in appearance over time) and coherence (regularity in changing appearances). Thus Hume proceeds to develop an account of how the imagination, fed with coherent and constant impressions, brings about belief in objects with continued (and therefore distinct) existence. Given coherent impressions, we have only one way of accounting for our observations consistently with past experience: we form the supposition that certain objects exist unperceived. And since this supposes more regularity than is found in past observation, causal reasoning alone cannot explain it: thus Hume invokes the imagination's tendency to continue in any "train of thinking" inertially, "like a galley put in motion by the oars". But to explain "so vast an edifice, as... the continu'd existence of all external bodies", Hume finds it necessary to bring constancy into his account, as follows: (1) Identity is characterised as invariableness and uninterruptedness over time. (2) Since the mind tends to confuse closely resembling ideas, it will naturally confuse a case of interrupted observation of an invariable object with a case of perfect identity. (3) This combination of perfect identity and interrupted observation creates cognitive dissonance, which is resolved by fabricating continued existence. (4) This fiction is enlivened into a full-fledged belief by the memory's "lively impressions" of the observed object.

But this naïve belief in the continued and distinct existence of our perceptions is false, as is easily shown by simple observations. Philosophers therefore distinguish mental perceptions from external objects. But, Hume argues, this philosophical "system of a double existence" could never arise directly from reason or the imagination. Instead, it is "the monstrous offspring of two principles", viz. our naïve belief in the continued and distinct existence of our perceptions, along with our more reflective conclusion that perceptions must depend upon the mind. It is only by passing through the naïve natural belief that the imagination fabricates this "arbitrarily invent" philosophical system. Hume ends by voicing strong doubts about any system based on "such trivial qualities of the fancy", and recommending "arelessness and in-attention" as the only remedy for scepticism.

Sections 3–6edit

Next, Hume presents a brief critique of "antient philosophy" (traditional Aristotelianism) and "modern philosophy" (post-Scientific Revolution mechanical philosophy), focusing on their rival conceptions of external objects. As for the incomprehensible "fictions of the antient philosophy", he thinks they can shed further light on human psychology. We begin with contradictions in "our ideas of bodies": between seeing bodies as ever-changing bundles of distinct qualities, and seeing bodies as simple unities that retain their identity across time. We reconcile these contradictions by fabricating "something unknown and invisible" that underlies change and unifies the distinct qualities together: i.e., the substance of traditional metaphysics. Similar fictions, fabricated by the imagination to resolve similar difficulties, include substantial forms, accidents, and occult qualities, all meaningless jargon used only to hide our ignorance. Modern philosophy, however, claims to disown the "trivial propensities of the imagination" and follow only solid reason (or, for Hume, "the solid, permanent, and consistent principles of the imagination"). Its "fundamental principle" is that secondary qualities ("colours, sounds, tastes, smells, heat and cold") are "nothing but impressions in the mind", as opposed to the primary qualities ("motion, extension, and solidity") that exist in reality. But Hume argues that primary qualities cannot be conceived apart from the secondary qualities. Thus if we follow solid reason and exclude the latter, we will be forced to contradict our own senses by excluding the former as well, thereby denying the entire external world.

Hume then examines "the nature of the mind", starting with the materialist-dualist debate over the substance of the mind. He rejects the whole question as "unintelligible", for we have no impression (and therefore no idea) of any substance, and defining "substance" as "something which may exist by itself" does not help (each of our perceptions, Hume argues, would then count as a distinct substance). Turning to the question of the "local conjunction" of mind and matter, he considers and endorses the anti-materialist argument which asks how unextended thoughts and feelings could possibly be conjoined at some location to an extended substance like a body. Hume then provides a psychological account of how we get taken in by such illusions (in his example, a fig and an olive are at opposite ends of a table, and we mistakenly suppose the sweet figgy taste to be in one location and the bitter olive taste to be in the other), arguing that unextended perceptions must somehow exist without having a location. But the contrary problem arises for dualists: how can extended perceptions (of extended objects) possibly be conjoined to a simple substance? Indeed, Hume waggishly adds, this is basically the same problem that theologians commonly press against Spinoza's naturalistic metaphysics: thus if the theologians manage to solve the problem of extended perceptions belonging to a simple substance, then they give "that famous atheist" Spinoza a solution to the problem of extended objects as modes of a simple substance. Finally, Hume examines causal relations, arguing on behalf of materialists that our observations of regular mind-body correlations are enough to show the causal dependence of the mind on the body, and that, since "we are never sensible of any connexion betwixt causes and effects" in general, our inability to detect any a priori connection between mind and body does nothing to show causal independence.

Finally, Hume weighs in on the topic of personal identity. Notoriously, he claims that introspective experience reveals nothing like a self (i.e., a mental substance with identity and simplicity), but only an ever-changing bundle of particular perceptions. And so he gives a psychological account of why we believe in personal identity, arguing that "the identity, which we ascribe to the mind of man, is only a fictitious one, and of a like kind with that which we ascribe to vegetables and animal bodies". Hume's account starts with our tendency to confound resembling but contrary ideas, viz. the idea of "a perfect identity" and the idea of "a succession of related objects", an absurdity we justify by means of "a fiction, either of something invariable and uninterrupted, or of something mysterious and inexplicable, or at least... a propensity to such fictions". Next, he argues that the everyday objects we ascribe identity to (e.g., trees, humans, churches, rivers) are indeed "such as consist of a succession of related objects, connected together by resemblance, contiguity, or causation": thus we overlook relatively minor changes, especially when slow and gradual, and especially when connected by "some common end or purpose" or "a sympathy of parts to their common end". Applying all this to personal identity, he argues that since all our perceptions are distinct from each other, and since we "never observe any real connexion among objects", our perceptions are merely associated together by the natural relations of resemblance (in part produced by the memory) and causation (only discovered by the memory). And consequently, leaving aside the fictions we invent, questions of personal identity are far too hazy to be answered with precision.

Section 7edit

Hume finishes Book 1 with a deeply sceptical interlude. Before continuing his "accurate anatomy of human nature" in Books 2 and 3, he anxiously ruminates: the "danger" of trusting his feeble faculties, along with the "solitude" of leaving behind established opinion, make his "bold enterprises" look foolhardy. All his thinking is based on the "seemingly... trivial" principles of the imagination ("the memory, senses, and understanding are, therefore, all of them founded on the imagination, or the vivacity of our ideas"), which leave us so tangled up in irresolvable contradictions, and so dismayingly ignorant of causal connections. And how much should we trust our imagination? Here a dilemma looms: if we follow the imagination wherever it leads, we end up with ridiculous absurdities; if we follow only its "general and more establish'd properties", we sink into total scepticism. As Hume writes: "we have, therefore, no choice left but betwixt a false reason and none at all." Faced with this dilemma, we tend to just forget about it and move on, though Hume finds himself verging on an intellectual breakdown. Happily, human nature steps in to save him: "I dine, I play a game of back-gammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends; and when after three or four hours' amusement, I wou'd return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strain'd, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any farther." And later, when he gets "tir'd with amusement and company", his intellectual curiosity and scholarly ambition resurface and lead him back into philosophy. And since no human can resist reflecting on transcendent matters anyway, we might as well follow philosophy instead of superstition, for "generally speaking, the errors in religion are dangerous; those in philosophy only ridiculous." In the end, Hume remains hopeful that he can "contribute a little to the advancement of knowledge" by helping to reorient philosophy to the study of human nature—a project made possible by subjecting even his sceptical doubts to a healthy scepticism.

Book 2: Of the Passionsedit

Part 1: Of pride and humilityedit

Sections 1–6edit

Hume begins by recalling Book 1's distinction between impressions of sensation ("original impressions", arising from physical causes outside the mind) and impressions of reflection ("secondary impressions", arising from other perceptions within the mind), examining only the latter. He divides these "reflective impressions"—"the passions, and other emotions resembling them"—into "the calm and the violent" (nearly imperceptible emotions of "beauty and deformity", and turbulent passions we experience more strongly) and into "direct and indirect" (depending on how complicated the causal story behind them is). Pride and humility are indirect passions, and Hume's account of the two is his leading presentation of the psychological mechanisms responsible for the indirect passions.