A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Chinese characters | |

|---|---|

"Chinese character" written in traditional (left) and simplified (right) forms | |

| Script type | Logographic

|

Time period | c. 13th century BCE – present |

| Direction |

|

| Languages | (among others) |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | (Proto-writing)

|

Child systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hani (500), Han (Hanzi, Kanji, Hanja) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Han |

| U+4E00–U+9FFF CJK Unified Ideographs (full list) | |

| Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Han characters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | sawgun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sawndip | 𭨡倱[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 한자 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chinese characters[a] are logographs used to write the Chinese languages and others from regions historically influenced by Chinese culture. Chinese characters have a documented history spanning over three millennia, representing one of the four independent inventions of writing accepted by scholars; of these, they comprise the only writing system continuously used since its invention. Over time, the function, style, and means of writing characters have evolved greatly. Unlike letters in alphabets that reflect the sounds of speech, Chinese characters generally represent morphemes, the units of meaning in a language. Writing a language's entire vocabulary requires thousands of different characters. Characters are created according to several different principles, where aspects of both shape and pronunciation may be used to indicate the character's meaning.

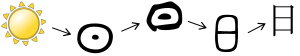

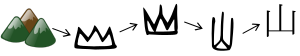

The first attested characters are oracle bone inscriptions made during the 13th century BCE in what is now Anyang, Henan, as part of divinations conducted by the Shang dynasty royal house. Character forms were originally highly pictographic in style, but evolved over time as writing spread across China. Numerous attempts have been made to reform the script, including the promotion of small seal script by the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE). Clerical script, which had matured by the early Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), abstracted the forms of characters—obscuring their pictographic origins in favour of making them easier to write. Following the Han, regular script emerged as the result of cursive influence on clerical script, and has been the primary style used for characters since. Informed by a long tradition of lexicography, states using Chinese characters have standardised their forms: broadly, simplified characters are used to write Chinese in mainland China, Singapore, and Malaysia, while traditional characters are used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau.

After being introduced in order to write Literary Chinese, characters were often adapted to write local languages spoken throughout the Sinosphere. In Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese, Chinese characters are known as kanji, hanja, and chữ Hán respectively. Writing traditions also emerged for some of the other languages of China, like the sawndip script used to write the Zhuang languages of Guangxi. Each of these written vernaculars used existing characters to write the language's native vocabulary, as well as the loanwords it borrowed from Chinese. In addition, each invented characters for local use. These languages function differently from Chinese, which has contributed to the replacement of characters with alphabets designed to write Korean and Vietnamese, leaving Japanese as the only major non-Chinese language still written with characters.

At the most basic level, characters are composed of strokes that are written according to a fixed order. Methods of writing characters have historically included being carved into stone, being inked with a brush onto silk, bamboo, or paper, and being printed using woodblocks and movable type. Technologies invented since the 19th century allowing for wider use of characters include telegraph codes and typewriters, as well as input methods and text encodings on computers.

Development

Chinese characters are accepted as representing one of four independent inventions of writing in human history.[b] In each instance, writing evolved from a system using two distinct types of ideographs. Ideographs could either be pictographs visually depicting objects or concepts, or fixed signs representing concepts only by shared convention. These systems are classified as proto-writing, because the techniques they used were insufficient to carry the meaning of spoken language by themselves.[3]

Various innovations were required for Chinese characters to emerge from proto-writing. Firstly, pictographs became distinct from simple pictures in use and appearance: for example, the pictograph 大, meaning 'large', was originally a picture of a large man, but one would need to be aware of its specific meaning in order to interpret the sequence 大鹿 as signifying 'large deer', rather than being a picture of a large man and a deer next to one another. Due to this process of abstraction, as well as to make characters easier to write, pictographs gradually became more simplified and regularised—often to the extent that the original objects represented are no longer obvious.[4]

This proto-writing system was limited to representing a relatively narrow range of ideas with a comparatively small library of symbols. This compelled innovations that allowed for symbols to directly encode spoken language.[5] In each historical case, this was accomplished by some form of the rebus technique, where the symbol for a word is used to indicate a different word with a similar pronunciation, depending on context.[6] This allowed for words that lacked a plausible pictographic representation to be written down for the first time. This technique pre-empted more sophisticated methods of character creation that would further expand the lexicon. The process whereby writing emerged from proto-writing took place over a long period; when the purely pictorial use of symbols disappeared, leaving only those representing spoken words, the process was complete.[7]

Classification

Chinese characters have been used in several different writing systems throughout history. The concept of a writing system includes both the written symbols themselves, called graphemes—which may include characters, numerals, or punctuation—as well as the rules by which they are used to record language.[8] Chinese characters are logographs, which are graphemes that represent units of meaning in a language. Specifically, characters represent the smallest units of meaning in a language, which are referred to as morphemes. Morphemes in Chinese—and therefore the characters used to write them—are nearly always a single syllable in length. In some special cases, characters may denote non-morphemic syllables as well; due to this, written Chinese is often characterised as morphosyllabic.[9][c] Logographs may be contrasted with letters in an alphabet, which generally represent phonemes, the distinct units of sound used by speakers of a language.[11] Despite their origins in picture-writing, Chinese characters are no longer ideographs capable of representing ideas directly; their comprehension relies on the reader's knowledge of the particular language being written.[12]

The areas where Chinese characters were historically used—sometimes collectively termed the Sinosphere—have a long tradition of lexicography attempting to explain and refine their use; for most of history, analysis revolved around a model first popularised in the 2nd-century Shuowen Jiezi dictionary.[13] More recent models have analysed the methods used to create characters, how characters are structured, and how they function in a given writing system.[14]

Structural analysis

Most characters can be analysed structurally as compounds made of smaller components (部件; bùjiàn), which are often independent characters in their own right, adjusted to occupy a given position in the compound.[15] Components within a character may serve a specific function: phonetic components provide a hint for the character's pronunciation, and semantic components indicate some element of the character's meaning. Components that serve neither function may be classified as pure signs with no particular meaning, other than their presence distinguishing one character from another.[16]

A straightforward structural classification scheme may consist of three pure classes of semantographs, phonographs and signs—having only semantic, phonetic, and form components respectively, as well as classes corresponding to each combination of component types.[17] Of the 3500 characters that are frequently used in Standard Chinese, pure semantographs are estimated to be the rarest, accounting for about 5% of the lexicon, followed by pure signs with 18%, and semantic–form and phonetic–form compounds together accounting for 19%. The remaining 58% are phono-semantic compounds.[18]

The Chinese palaeographer Qiu Xigui (b. 1935) presents three principles of character function adapted from earlier proposals by Tang Lan (1901–1979) and Chen Mengjia (1911–1966),[19] with semantographs describing all characters whose forms are wholly related to their meaning, regardless of the method by which the meaning was originally depicted, phonographs that include a phonetic component, and loangraphs encompassing existing characters that have been borrowed to write other words. Qiu also acknowledges the existence of character classes that fall outside of these principles, such as pure signs.[20]

Semantographs

Pictographs

Most of the oldest characters are pictographs (象形; xiàngxíng), representational pictures of physical objects.[21] Examples include 日 ('Sun'), 月 ('Moon'), and 木 ('tree'). Over time, the forms of pictographs have been simplified in order to make them easier to write.[22] As a result, it is often no longer evident what thing was originally being depicted by a pictograph; without knowing the context of its origin in picture-writing, it may be interpreted instead as a pure sign. However, if its use in compounds still reflects a pictograph's original meaning, as with 日 in 晴 ('clear sky'), it can still be analysed as a semantic component.[23][24]

Pictographs have often been extended from their original meanings to take on additional layers of metaphor and synecdoche, which sometimes displace the character's original sense. This process has sometimes created excess ambiguity between the different senses of a character, which is usually resolved by creating new compound characters.[25]

Indicatives

Indicatives (指事; zhǐshì), also called simple ideographs or self-explanatory characters,[21] are visual representations of abstract concepts that lack any tangible form. Examples include 上 ('up') and 下 ('down')—these characters were originally written as dots placed above and below a line, and later evolved into their present forms with less potential for graphical ambiguity in context.[26] More complex indicatives include 凸 ('convex'), 凹 ('concave'), and 平 ('flat and level').[27]

Compound ideographs

Compound ideographs (会意; 會意; huìyì)—also called logical aggregates, associative idea characters, or syssemantographs—combine other characters to convey a new, synthetic meaning. A canonical example is 明 ('bright'), interpreted as the juxtaposition of the two brightest objects in the sky: ⽇ 'SUN' and ⽉ 'MOON', together expressing their shared quality of brightness. Other examples include 休 ('rest'), composed of pictographs ⼈ 'MAN' and ⽊ 'TREE', and 好 ('good'), composed of ⼥ 'WOMAN' and ⼦ 'CHILD'.[28]

Many traditional examples of compound ideographs are now believed to have actually originated as phono-semantic compounds, made obscure by subsequent changes in pronunciation.[29] For example, the Shuowen Jiezi describes 信 ('trust') as an ideographic compound of ⼈ 'MAN' and ⾔ 'SPEECH', but modern analyses instead identify it as a phono-semantic compound—though with disagreement as to which component is phonetic.[30] Peter A. Boodberg and William G. Boltz go so far as to deny that any compound ideographs were devised in antiquity, maintaining that secondary readings that are now lost are responsible for the apparent absence of phonetic indicators,[31] but their arguments have been rejected by other scholars.[32]

Phonographs

Phono-semantic compounds

Phono-semantic compounds (形声; 形聲; xíngshēng) are composed of at least one semantic component and one phonetic component.[33] They may be formed by one of several methods, often by adding a phonetic component to disambiguate a loangraph, or by adding a semantic component to represent a specific extension of a character's meaning.[34] Examples of phono-semantic compounds include 河 (hé; 'river'), 湖 (hú; 'lake'), 流 (liú; 'stream'), 沖 (chōng; 'surge'), and 滑 (huá; 'slippery'). Each of these characters have three short strokes on their left-hand side: 氵, a simplified combining form of ⽔ 'WATER'. This component serves a semantic function in each example, indicating the character has some meaning related to water. The remainder of each character is its phonetic component: 湖 (hú) is pronounced identically to 胡 (hú) in Standard Chinese, 河 (hé) is pronounced similarly to 可 (kě), and 沖 (chōng) is pronounced similarly to 中 (zhōng).[35]

The phonetic components of most compounds may only provide an approximate pronunciation, even before subsequent sound shifts in the spoken language. Some characters may only have the same initial or final sound of a syllable in common with phonetic components.[36] A phonetic series comprises all the characters created using the same phonetic component, which may have diverged significantly in their pronunciations over time. For example, 茶 (chá; caa4; 'tea') and 途 (tú; tou4; 'route') are part of the phonetic series of characters using 余 (yú; jyu4), a literary first-person pronoun. The Old Chinese pronunciations of these characters were similar, but the phonetic component no longer serves as a useful hint for their pronunciation due to subsequent sound shifts.[37]

Loangraphs

The phenomenon of existing characters being adapted to write other words with similar pronunciations was necessary in the initial development of Chinese writing, and has remained common throughout its subsequent history. Some loangraphs (假借; jiǎjiè; 'borrowing') are introduced to represent words previously lacking another written form—this is often the case with abstract grammatical particles such as 之 and 其.[38] The process of characters being borrowed as loangraphs should not be conflated with the distinct process of semantic extension, where a word acquires additional senses, which often remain written with the same character. As both processes often result in a single character form being used to write several distinct meanings, loangraphs are often misidentified as being the result of semantic extension, and vice versa.[39]

Loangraphs are also used to write words borrowed from other languages, such as the various Buddhist terminology introduced to China in antiquity, as well as contemporary non-Chinese words and names. For example, each character in the name 加拿大 (Jiānádà; 'Canada') is often used as a loangraph for its respective syllable. However, the barrier between a character's pronunciation and meaning is never total: when transcribing into Chinese, loangraphs are often chosen deliberately as to create certain connotations. This is regularly done with corporate brand names: for example, Coca-Cola's Chinese name is 可口可乐; 可口可樂 (Kěkǒu Kělè; 'delicious enjoyable').[40][41][42]

Signs

Some characters and components are pure signs, whose meaning merely derives from their having a fixed and distinct form. Basic examples of pure signs are found with the numerals beyond four, e.g. 五 ('five') and 八 ('eight'), whose forms do not give visual hints to the quantities they represent.[43]

Traditional Shuowen Jiezi classification

The Shuowen Jiezi is a character dictionary authored c. 100 CE by the scholar Xu Shen (c. 58 – c. 148 CE). In its postface, Xu analyses what he sees as all the methods by which characters are created. Later authors iterated upon Xu's analysis, developing a categorisation scheme known as the 'six writings' (六书; 六書; liùshū), which identifies every character with one of six categories that had previously been mentioned in the Shuowen Jiezi. For nearly two millennia, this scheme was the primary framework for character analysis used throughout the Sinosphere.[44] Xu based most of his analysis on examples of Qin seal script that were written down several centuries before his time—these were usually the oldest specimens available to him, though he stated he was aware of the existence of even older forms.[45] The first five categories are pictographs, indicatives, compound ideographs, phono-semantic compounds, and loangraphs. The sixth category is given as 轉注 (zhuǎnzhù; 'reversed and refocused') by Xu; however, its definition is unclear, and it is generally disregarded by modern scholars.[46]

Modern scholars agree that the theory presented in the Shuowen Jiezi is problematic, failing to fully capture the nature of Chinese writing, both in the present, as well as at the time Xu was writing.[47] Traditional Chinese lexicography as embodied in the Shuowen Jiezi has suggested implausible etymologies for some characters,[48] and some of its definitions are considered to be ill-defined, such as the distinction between pictographs and indicatives.[34] However, the 'six writings' model has proven resilient, and continues to serve as a guide for students memorising characters.[49]

History

The broadest trend in the evolution of Chinese characters over their history has been simplification, both in graphical shape (字形; zìxíng), the "external appearances of individual graphs", and in graphical form (字体; 字體; zìtǐ), "overall changes in the distinguishing features of graphic shape and calligraphic style, in most cases refer to rather obvious and rather substantial changes".[51] The traditional notion of an orderly procession of script styles, each suddenly appearing and displacing the one previous, has been disproven by later scholarship and archaeological work. Instead, scripts evolved gradually, with several coexisting in a given area.[52]

Traditional invention narrative

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Chinese_charactersText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk