A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~569,000 or 2.50% of the population of Taiwan (Non-status and unrecognized indigenous peoples excluded) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Taiwan and Orchid Island | |

| Languages | |

| Formosan languages (Atayal, Bunun, Amis, Paiwan, others) or Yami language Chinese languages (Mandarin, Hokkien, Hakka) Japanese language, Yilan Creole Japanese | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Christianity, minority Animism, Buddhism[1] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Taiwanese people, other Austronesians |

| Taiwanese indigenous peoples | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣原住民 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾原住民 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Taiwanese original inhabitants | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taiwanese indigenous peoples |

|---|

|

| Peoples |

|

Nationally Recognized Locally recognized Unrecognized |

| Related topics |

Taiwanese indigenous peoples, also known as Formosans, Native Taiwanese or Austronesian Taiwanese,[2][3] and formerly as Taiwanese aborigines, Takasago people or Gaoshan people,[4] are the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, with the nationally recognized subgroups numbering about 569,000 or 2.38% of the island's population. This total is increased to more than 800,000 if the indigenous peoples of the plains in Taiwan are included, pending future official recognition. When including those of mixed ancestry, such a number is possibly more than a million. Academic research suggests that their ancestors have been living on Taiwan for approximately 15,000 years. A wide body of evidence suggests that the Taiwanese indigenous peoples had maintained regular trade networks with numerous regional cultures of Southeast Asia before the Han Chinese colonists began settling on the island from the 17th century, at the behest of the Dutch colonial administration and later by successive governments towards the 20th century.[5][6]

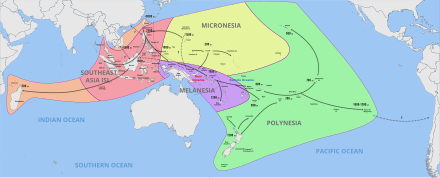

Taiwanese indigenous peoples are Austronesians, with linguistic, genetic and cultural ties to other Austronesian peoples.[7] Taiwan is the origin and linguistic homeland of the oceanic Austronesian expansion, whose descendant groups today include the majority of the ethnic groups throughout many parts of East and Southeast Asia as well as Oceania and even Africa which includes Brunei, East Timor, Indonesia, Malaysia, Madagascar, Philippines, Micronesia, Island Melanesia and Polynesia. The Chams and Utsul of contemporary central and southern Vietnam and Hainan respectively are also a part of the Austronesian family.

For centuries, Taiwan's indigenous inhabitants experienced economic competition and military conflict with a series of colonizing newcomers. Centralized government policies designed to foster language shift and cultural assimilation, as well as continued contact with the colonizers through trade, inter-marriage and other intercultural processes, have resulted in varying degrees of language death and loss of original cultural identity. For example, of the approximately 26 known languages of the Taiwanese indigenous peoples – collectively referred to as the Formosan languages – at least ten are now extinct, five are moribund[8] and several are to some degree endangered. These languages are of unique historical significance since most historical linguists consider Taiwan to be the original homeland of the Austronesian language family.[5]

Due to discrimination or repression throughout the centuries, the indigenous peoples of Taiwan have experienced economic and social inequality, including a high unemployment rate and substandard education. Some indigenous groups today continue to be unrecognized by the government. Since the early 1980s, many indigenous groups have been actively seeking a higher degree of political self-determination and economic development.[9] The revival of ethnic pride is expressed in many ways by the indigenous peoples, including the incorporation of elements of their culture into cultural commodities such as cultural tourism, pop music and sports. Taiwan's Austronesian speakers were formerly distributed over much of the Taiwan archipelago, including the Central Mountain Range villages along the alluvial plains, as well as Orchid Island, Green Island, and Liuqiu Island.

The bulk of contemporary Taiwanese indigenous peoples mostly reside both in their traditional mountain villages as well as increasingly in Taiwan's urban areas. There are also the plains indigenous peoples, which have always lived in the lowland areas of the island. Ever since the end of the White Terror, some efforts have been under way in indigenous communities to revive traditional cultural practices and preserve their distinct traditional languages on the now Han Chinese majority island and for the latter to better understand more about them.[10]

The founding of NDHU College of Indigenous Studies in 2001 signify an important milestone for the revitalization activity of Taiwanese indigenous people, which is Taiwan's first ethnocentric education system.[11] The Austronesian Cultural Festival in Taitung City is one means by which community members promote indigenous culture. In addition, several indigenous communities have become extensively involved in the tourism and ecotourism industries with the goal of achieving increased economic self-reliance and maintaining cultural integration.[12]

Terminology

Taxonomies imposed by colonizing forces divided the aborigines into named subgroups, referred to as "tribes". These divisions did not always correspond to distinctions drawn by the indigenous themselves. However, the categories have become so firmly established in government and popular discourse over time that they have become de facto distinctions, serving to shape in part today's political discourse within the Republic of China (ROC), and affecting Taiwan's policies regarding indigenous peoples.[citation needed]

The Han sailor Chen Di, in his Record of the Eastern Seas (1603), identifies the indigenous people of Taiwan as simply "Eastern Savages" (東番; Dongfan), while the Dutch referred to Taiwan's original inhabitants as "Indians" or "blacks", based on their prior colonial experience in what is currently Indonesia.[13]

Beginning nearly a century later, as the rule of the Qing Empire expanded over wider groups of people, writers and gazetteers recast their descriptions away from reflecting degree of acculturation, and toward a system that defined the aborigines relative to their submission or hostility to Qing rule. Qing used the term "raw/wild/uncivilized" (生番) to define those people who had not submitted to Qing rule, and "cooked/tamed/civilized" (熟番) for those who had pledged their allegiance through their payment of a head tax.[note 1] According to the standards of the Qianlong Emperor and successive regimes, the epithet "cooked" was synonymous with having assimilated to Han cultural norms, and living as a subject of the Empire, but it retained a pejorative designation to signify the perceived cultural lacking of the non-Han people.[15] This designation reflected the prevailing idea that anyone could be civilized/tamed by adopting Confucian social norms.[16][17]

As the Qing consolidated their power over the plains and struggled to enter the mountains in the late 19th century, the terms Pingpu (平埔族; Píngpǔzú; 'Plains peoples') and Gaoshan (高山族; Gāoshānzú; 'High Mountain peoples') were used interchangeably with the epithets "civilized" and "uncivilized".[18] During Japanese rule (1895–1945), anthropologists from Japan maintained the binary classification. In 1900 they incorporated it into their own colonial project by employing the term Peipo (平埔) for the "civilized tribes", and creating a category of "recognized tribes" for the aborigines who had formerly been called "uncivilized". The Musha Incident of 1930 led to many changes in aboriginal policy, and the Japanese government began referring to them as Takasago people (高砂族, Takasago-zoku).[19]

The latter group included the Atayal, Bunun, Tsou, Saisiat, Paiwan, Puyuma, and Amis peoples. The Tao (Yami) and Rukai were added later, for a total of nine recognized peoples.[20] During the early period of Chinese Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) rule the terms Shandi Tongbao (山地同胞) "mountain compatriots" and Pingdi Tongbao (平地同胞) "plains compatriots" were invented, to remove the presumed taint of Japanese influence and reflect the place of Taiwan's indigenous people in the Chinese Nationalist state.[21] The KMT later adopted the use of all the earlier Japanese groupings except Peipo.

Despite recent changes in the field of anthropology and a shift in government objectives, the Pingpu and Gaoshan labels in use today maintain the form given by the Qing to reflect indigenous' acculturation to Han culture. [citation needed]The current recognized indigenous are all regarded as Gaoshan, though the divisions are not and have never been based strictly on geographical location. The Amis, Saisiat, Tao and Kavalan are all traditionally Eastern Plains cultures.[22] The distinction between Pingpu and Gaoshan people continues to affect Taiwan's policies regarding indigenous peoples, and their ability to participate effectively in government.[23]

Although the ROC's Government Information Office officially lists 16 major groupings as "tribes," the consensus among scholars maintains that these 16 groupings do not reflect any social entities, political collectives, or self-identified alliances dating from pre-modern Taiwan.[24] The earliest detailed records, dating from the Dutch arrival in 1624, describe the aborigines as living in independent villages of varying size. Between these villages there was frequent trade, intermarriage, warfare and alliances against common enemies. Using contemporary ethnographic and linguistic criteria, these villages have been classed by anthropologists into more than 20 broad (and widely debated) ethnic groupings,[25][26] which were never united under a common polity, kingdom or "tribe".[27]

| Atayal | Saisiyat | Bunun | Tsou | Rukai | Paiwan | Puyuma | Amis | Yami | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27,871 | 770 | 16,007 | 2,325 | 13,242 | 21,067 | 6,407 | 32,783 | 1,487 | 121,950 |

Since 2005, some local governments, including Tainan City in 2005, Fuli, Hualien in 2013, and Pingtung County in 2016, have begun to recognize Taiwanese Plain Indigenous peoples. The numbers of people who have successfully registered, including Kaohsiung City Government that has opened to register but not yet recognized, as of 2017 are:[29][30][31][32]

| Siraya | Taivoan | Makatao | Not Specific | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tainan | 11,830 | – | – | – | 11,830 |

| Kaohsiung | 107 | 129 | – | 237 | 473 |

| Pingtung | – | – | 1,803 | 205 | 2,008 |

| Fuli, Hualien | – | – | – | 100 | 100 |

| Total | 11,937 | 129 | 1,803 | 542 | 14,411 |

Recognized peoples

Indigenous ethnic groups recognized by Taiwan

Taiwan officially recognizes distinct people groups among the indigenous community based upon the qualifications drawn up by the Council of Indigenous Peoples (CIP).[33] To gain this recognition, communities must gather a number of signatures and a body of supporting evidence with which to successfully petition the CIP. Formal recognition confers certain legal benefits and rights upon a group, as well as providing them with the satisfaction of recovering their separate identity as an ethnic group. As of June 2014, 16 people groups have been recognized.[34]

The Council of Indigenous Peoples consider several limited factors in a successful formal petition. The determining factors include collecting member genealogies, group histories and evidence of a continued linguistic and cultural identity.[35][36] The lack of documentation and the extinction of many indigenous languages as the result of colonial cultural and language policies have made the prospect of official recognition of many ethnicities a remote possibility. Current trends in ethno-tourism have led many former Plains Aborigines to continue to seek cultural revival.[37]

Among the Plains groups that have petitioned for official status, only the Kavalan and Sakizaya have been officially recognized. The remaining twelve recognized groups are traditionally regarded as mountain indigenous people.[citation needed]

Other indigenous groups or subgroups that have pressed for recovery of legal indigenous status include Chimo (who have not formally petitioned the government, see Lee 2003), Kakabu, Makatao, Pazeh, Siraya,[38] and Taivoan. The act of petitioning for recognized status, however, does not always reflect any consensus view among scholars that the relevant group should in fact be categorized as a separate ethnic group. The Siraya will become the 17th ethnic group to be recognized once their status, already recognized by the courts in May 2018, is officially announced by the central government.[39]

There is discussion among both scholars and political groups regarding the best or most appropriate name to use for many of the people groups and their languages, as well as the proper romanization of that name. Commonly cited examples of this ambiguity include (Seediq/Sediq/Truku/Taroko) and (Tao/Yami).

Nine people groups were originally recognized before 1945 by the Japanese government.[33] The Thao, Kavalan and Truku were recognized by Taiwan's government in 2001, 2002 and 2004 respectively. The Sakizaya were recognized as a 13th on 17 January 2007,[40] and on 23 April 2008 the Sediq were recognized as Taiwan's 14th official ethnic group.[41] Previously the Sakizaya had been listed as Amis and the Sediq as Atayal. Hla'alua and Kanakanavu were recognized as the 15th and 16th ethnic group on 26 June 2014.[34] A full list of the recognized ethnic groups of Taiwan, as well as some of the more commonly cited unrecognized peoples, is as follows:

- Recognized: Ami, Atayal, Bunun, Hla'alua, Kanakanavu, Kavalan, Paiwan, Puyuma, Rukai, Saisiyat, Tao, Thao, Tsou, Truku, Sakizaya and Sediq.

- Locally recognized: Makatao (in Pingtung and Fuli), Siraya (in Tainan and Fuli), Taivoan (in Fuli)

- Unrecognized: Babuza, Basay, Hoanya, Ketagalan, Luilang, Pazeh/Kaxabu, Papora, Qauqaut, Taokas, Trobiawan.

Indigenous Taiwanese in the PRC

The People's Republic of China (PRC) officially recognizes indigenous Taiwanese as one of its ethnic groups under the name Gāoshān (高山, lit. 'high mountain') The 2000 census identified 600 thousand Gāoshān living in Taiwan Island; other surveys suggest this accounted for 21 thousand Amis, 51 thousand Bunun, 10.5 thousand Paiwan, with the remainder belonging to other peoples.[4] They are descendants of Taiwanese indigenous living on this island before the 1949 evacuation of the PRC and tracking back further to the Dutch colony in the 17th century.[4] In Zhengzhou, Henan, there exists a "Taiwan Village" (台灣村) whose inhabitants' ancestors migrated from Taiwan during the Kangxi era of the Qing dynasty. In 2005, 2,674 people of the village identified themselves as Gaoshan.[42][43]

Assimilation and acculturation

Archeological, linguistic and anecdotal evidence suggests that Taiwan's indigenous peoples have undergone a series of cultural shifts to meet the pressures of contact with other societies and new technologies.[44] Beginning in the early 17th century, indigenous Taiwanese faced broad cultural change as the island became incorporated into the wider global economy by a succession of competing colonial regimes from Europe and Asia.[45][46] In some cases groups of indigenous resisted colonial influence, but other groups and individuals readily aligned with the colonial powers. This alignment could be leveraged to achieve personal or collective economic gain, collective power over neighboring villages or freedom from unfavorable societal customs and taboos involving marriage, age-grade and child birth.[47][48]

Particularly among the Plains indigenous people, as the degree of the "civilizing projects" increased during each successive regime, the aborigines found themselves in greater contact with outside cultures. The process of acculturation and assimilation sometimes followed gradually in the wake of broad social currents, particularly the removal of ethnic markers (such as bound feet, dietary customs and clothing), which had formerly distinguished ethnic groups on Taiwan.[49] The removal or replacement of these brought about an incremental transformation from "Fan" (番, barbarian) to the dominant Confucian "Han" culture.[50] During the Japanese and KMT periods centralized modernist government policies, rooted in ideas of Social Darwinism and culturalism, directed education, genealogical customs and other traditions toward ethnic assimilation.[51][52]

Within the Taiwanese Han Hoklo community itself, differences in culture indicate the degree to which mixture with aboriginals took place, with most pure Hoklo Han in Northern Taiwan having almost no Aboriginal admixture, which is limited to Hoklo Han in Southern Taiwan.[53] Plains aboriginals who were mixed and assimilated into the Hoklo Han population at different stages were differentiated by the historian Melissa J. Brown between "short-route" and "long-route".[54] The ethnic identity of assimilated Plains Aboriginals in the immediate vicinity of Tainan was still known since a pure Hoklo Taiwanese girl was warned by her mother to stay away from them.[55] The insulting name "fan" was used against Plains indigenous by the Taiwanese, and the Hoklo Taiwanese speech was forced upon Aborigines like the Pazeh.[56] Hoklo Taiwanese has replaced Pazeh and driven it to near extinction.[57] Indigenous status has been requested by Plains indigenous peoples.[58]

Current forms of assimilation

Many of these forms of assimilation are still at work today. For example, when a central authority nationalizes one language, that attaches economic and social advantages to the prestige language. As generations pass, use of the indigenous language often fades or disappears, and linguistic and cultural identity recede as well. However, some groups are seeking to revive their indigenous identities.[59] One important political aspect of this pursuit is petitioning the government for official recognition as a separate and distinct ethnic group.[citation needed]

The complexity and scope of aboriginal assimilation and acculturation on Taiwan has led to three general narratives of Taiwanese ethnic change. The oldest holds that Han migration from Fujian and Guangdong in the 17th century pushed the Plains indigenous peoples into the mountains, where they became the Highland peoples of today.[60] A more recent view asserts that through widespread intermarriage between Han and aborigines between the 17th and 19th centuries, the aborigines were completely Sinicized.[61][62] Finally, modern ethnographical and anthropological studies have shown a pattern of cultural shift mutually experienced by both Han and Plains indigenous, resulting in a hybrid culture. Today people who comprise Taiwan's ethnic Han demonstrate major cultural differences from Han elsewhere.[63][37]

Surnames and identity

Several factors encouraged the assimilation of the Plains indigenous.[note 2] Taking a Han name was a necessary step in instilling Confucian values in the aborigines.[65] Confucian values were necessary to be recognized as a full person and to operate within the Confucian Qing state.[66] A surname in Han society was viewed as the most prominent legitimizing marker of a patrilineal ancestral link to the Yellow Emperor (Huang Di) and the Five Emperors of Han mythology.[67] Possession of a Han surname, then, could confer a broad range of significant economic and social benefits upon indigenous, despite a prior non-Han identity or mixed parentage. In some cases, members of Plains indigenous adopted the Han surname Pan (潘) as a modification of their designated status as Fan (番: "barbarian").[68] One family of Pazeh became members of the local gentry.[69][70] complete with a lineage to Fujian province. In other cases, families of Plains indigenous adopted common Han surnames, but traced their earliest ancestor to their locality in Taiwan.[citation needed]

In many cases, large groups of immigrant Han would unite under a common surname to form a brotherhood. Brotherhoods were used as a form of defense, as each sworn brother was bound by an oath of blood to assist a brother in need. The brotherhood groups would link their names to a family tree, in essence manufacturing a genealogy based on names rather than blood, and taking the place of the kinship organizations commonly found in China. The practice was so widespread that today's family books are largely unreliable.[66][71] Many Plains indigenous joined the brotherhoods to gain protection of the collective as a type of insurance policy against regional strife, and through these groups they took on a Han identity with a Han lineage.

The degree to which any one of these forces held sway over others is unclear. Preference for one explanation over another is sometimes predicated upon a given political viewpoint. The cumulative effect of these dynamics is that by the beginning of the 20th century the Plains indigenous were almost completely acculturated into the larger ethnic Han group, and had experienced nearly total language shift from their respective Formosan languages to Chinese. In addition, legal barriers to the use of traditional surnames persisted until the 1990s, and cultural barriers remain. Indigenous peoples were not permitted to use their indigenous traditional names on official identification cards until 1995 when a ban on using indigenous names dating from 1946 was finally lifted.[72] One obstacle is that household registration forms allow a maximum of 15 characters for personal names. However, indigenous names are still phonetically translated into Chinese characters, and many names require more than the allotted space.[73] In April 2022, the Constitutional Court ruled that Article 4, Paragraph 2 of the Status Act for Indigenous Peoples was unconstitutional. The paragraph, which reads "Children of intermarriages between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous Peoples taking the surname of the indigenous father or mother, or using a traditional Indigenous Peoples name, shall acquire Indigenous Peoples status," was ruled unconstitutional after a non-indigenous father had taken his daughter to a household registration office to register her Truku descent. Though the applicant was of Truku descent through her mother, her application used her father's Chinese surname and was denied. The Constitutional Court ruled that the law, as written, was a violation of gender equality guaranteed by Article 7 of the Constitution, since children in Taiwan usually take their father's surname, which in practice, meant that indigenous status could be acquired via paternal descent, but not maternal descent.[74]

History of the Taiwanese indigenous peoples

Indigenous Taiwanese are Austronesian peoples, with linguistic and genetic ties to other Austronesian ethnic groups, such as peoples of the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Madagascar, and Oceania.[75][76] Chipped-pebble tools dating from perhaps as early as 15,000 years ago suggest that the initial human inhabitants of Taiwan were Paleolithic cultures of the Pleistocene era. These people survived by eating marine life. Archeological evidence points to an abrupt change to the Neolithic era around 6,000 years ago, with the advent of agriculture, domestic animals, polished stone adzes and pottery. The stone adzes were mass-produced on Penghu and nearby islands, from the volcanic rock found there. This suggests heavy sea traffic took place between these islands and Taiwan at this time.[77]

From around 5000 to 1500 BC, Taiwanese indigenous peoples started a seaborne migration to the island of Luzon in the Philippines, intermingling with the older Negrito populations of the islands. This was the beginning of the Austronesian expansion. They spread throughout the rest of the Philippines and eventually migrated further to the other islands of Southeast Asia, Micronesia, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar. Taiwan is the homeland of the Austronesian languages.[5][78][79][80][81]

There is evidence that indigenous Taiwanese continued trading with the Philippines in the Sa Huynh-Kalanay Interaction Sphere. Eastern Taiwan was the source of jade for the lingling-o jade industry in the Philippines and the Sa Huỳnh culture of Vietnam.[82][83][84][85] This trading network began between the animist communities of Taiwan and the Philippines which later became the Maritime Jade Road, one of the most extensive sea-based trade networks of a single geological material in the prehistoric world. It was in existence for 3,000 years from 2000 BCE to 1000 CE.[86][87][88][89]

Four centuries of non-indigenous rule can be viewed through several changing periods of governing power and shifting official policy toward aborigines. From the 17th century until the early 20th, the impact of the foreign settlers—the Dutch, Spanish, and Han—was more extensive on the Plains peoples. They were far more geographically accessible than the Mountain peoples, and thus had more dealings with the foreign powers. The reactions of indigenous people to imperial power show not only acceptance, but also incorporation or resistance through their cultural practices [90][91]

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Plains peoples had largely been assimilated into contemporary Taiwanese culture as a result of European and Han colonial rule. Until the latter half of the Japanese colonial era the Mountain peoples were not entirely governed by any non-indigenous polity. However, the mid-1930s marked a shift in the intercultural dynamic, as the Japanese began to play a far more dominant role in the culture of the Highland groups. This increased degree of control over the Mountain peoples continued during Kuomintang rule. Within these two broad eras, there were many differences in the individual and regional impact of the colonizers and their "civilizing projects". At times the foreign powers were accepted readily, as some communities adopted foreign clothing styles and cultural practices (Harrison 2003), and engaged in cooperative trade in goods such as camphor, deer hides, sugar, tea, and rice.[92] At numerous other times changes from the outside world were forcibly imposed.

Plains indigenous peoples

The plains indigenous peoples mainly lived in stationary village sites surrounded by defensive walls of bamboo. The village sites in southern Taiwan were more populated than other locations. Some villages supported a population of more than 1,500 people, surrounded by smaller satellite villages.[93] Siraya villages were constructed of dwellings made of thatch and bamboo, raised 2 m (6.6 ft) from the ground on stilts, with each household having a barn for livestock. A watchtower was located in the village to look out for headhunting parties from the Highland peoples. The concept of property was often communal, with a series of conceptualized concentric rings around each village. The innermost ring was used for gardens and orchards that followed a fallowing cycle around the ring. The second ring was used to cultivate plants and natural fibers for the exclusive use of the community. The third ring was for exclusive hunting and deer fields for community use. The plains indigenous peoples hunted herds of spotted Formosan sika deer, Formosan sambar deer and Reeves's muntjac as well as conducting light millet farming. Sugar and rice were grown as well, but mostly for use in preparing wine.[94]

Many of the plains indigenous peoples were matrilineal/matrifocal societies. A man married into a woman's family after a courtship period during which the woman was free to reject as many men as she wished. In the age-grade communities, couples entered into marriage in their mid-30s when a man would no longer be required to perform military service or hunt heads on the battle-field. In the matriarchal system of the Siraya, it was also necessary for couples to abstain from marriage until their mid-30s, when the bride's father would be in his declining years and would not pose a challenge to the new male member of the household. It was not until the arrival of the Dutch Reformed Church in the 17th century that the marriage and child-birth taboos were abolished. There is some indication that many of the younger members of Sirayan society embraced the Dutch marriage customs as a means to circumvent the age-grade system in a push for greater village power.[95] Almost all indigenous peoples in Taiwan have traditionally had a custom of sexual division of labor. Women did the sewing, cooking and farming, while the men hunted and prepared for military activity and securing enemy heads in headhunting raids, which was a common practice in early Taiwan. Women were also often found in the office of priestesses or mediums to the gods.

For centuries, Taiwan's aboriginal peoples experienced economic competition and military conflict with a series of colonizing peoples. Centralized government policies designed to foster language shift and cultural assimilation, as well as continued contact with the colonizers through trade, intermarriage and other dispassionate intercultural processes, have resulted in varying degrees of language death and loss of original cultural identity. For example, of the approximately 26 known languages of the Taiwanese aborigines (collectively referred to as the Formosan languages), at least ten are extinct, five are moribund[8] and several are to some degree endangered. These languages are of unique historical significance, since most historical linguists consider Taiwan to be the original homeland of the Austronesian language family.[5]

Contact with Chinese

Early Chinese histories refer to visits to eastern islands that some historians identify with Taiwan. Troops of the Three Kingdoms state of Eastern Wu are recorded visiting an island known as Yizhou in the spring of 230. They brought back several thousand natives but 80 to 90 percent of the soldiers died to unknown diseases.[96] Some scholars have identified this island as Taiwan while others do not.[97] The Book of Sui relates that Emperor Yang of the Sui dynasty sent three expeditions to a place called "Liuqiu" early in the 7th century.[98] They brought back captives, cloth, and armour. The Liuqiu described by the Book of Sui had pigs and chicken but no cows, sheep, donkeys, or horses. It produced little iron, had no writing system, taxation, or penal code, and was ruled by a king with four or five commanders. The natives used stone blades and practiced slash-and-burn agriculture to grow rice, millet, sorghum, and beans.[96] Later the name Liuqiu (whose characters are read in Japanese as "Ryukyu") referred to the island chain to the northeast of Taiwan, but some scholars believe it may have referred to Taiwan in the Sui period.[99]

During the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Han Chinese people started visiting Taiwan.[100] The Yuan emperor Kublai Khan sent officials to the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1292 to demand its loyalty to the Yuan dynasty, but the officials ended up in Taiwan and mistook it for Ryukyu. After three soldiers were killed, the delegation immediately retreated to Quanzhou in China. Another expedition was sent in 1297. Wang Dayuan visited Taiwan in 1349 and noted that the customs of its inhabitants were different from those of Penghu's population, but did not mention the presence of other Chinese. He mentioned the presence of Chuhou pottery from present day Lishui, Zhejiang, suggesting that Chinese merchants had already visited the island by the 1340s.[101]

By the early 16th century, increasing numbers of Chinese fishermen, traders and pirates were visiting the southwestern part of the island. Some merchants from Fujian were familiar enough with the indigenous peoples of Taiwan to speak Formosan languages.[100] The people of Fujian sailed closer to Taiwan and the Ryukyus in the mid-16th century to trade with Japan while evading Ming authorities. Chinese who traded in Southeast Asia also began taking an East Sea Compass Course (dongyang zhenlu) that passed southwestern and southern Taiwan. Some of them traded with the Taiwanese aborigines. During this period, Taiwan was referred to as Xiaodong dao ("little eastern island") and Dahui guo ("the country of Dahui"), a corruption of Tayouan, a tribe that lived on an islet near modern Tainan from which the name "Taiwan" is derived. By the late 16th century, Chinese from Fujian were settling in southwestern Taiwan. The Chinese pirates Lin Daoqian and Lin Feng visited Taiwan in 1563 and 1574 respectively. Lin Daoqian was a pirate from Chaozhou who fled to Beigang in southwestern Taiwan and left shortly after. Lin Feng moved his pirate forces to Wankan (in modern Chiayi County) in Taiwan on 3 November 1574 and used it as a base to launch raids. They left for Penghu after being attacked by natives and the Ming navy dislodged them from their bases. He later returned to Wankan on 27 December 1575 but left for Southeast Asia after losing a naval encounter with Ming forces on 15 January 1576.[102][103] The pirate Yan Siqi also used Taiwan as a base.[100] In 1593, Ming officials started issuing ten licenses each year for Chinese junks to trade in northern Taiwan. Chinese records show that after 1593, each year five licenses were granted for trade in Keelung and five licenses for Tamsui. However these licenses merely acknowledged already existing illegal trade at these locations.[104]

Initially Chinese merchants arrived in northern Taiwan and sold iron and textiles to the Taiwanese indigenous peoples in return for coal, sulfur, gold, and venison. Later the southwestern part of Taiwan surpassed northern Taiwan as the destination for Chinese traders. The southwest had mullet fish, which drew more than a hundred fishing junks from Fujian each year during winter. The fishing season lasted six to eight weeks. Some of them camped on Taiwan's shores and many began trading with the indigenous people for deer products. The southwestern Taiwanese trade was of minor importance until after 1567 when it was used as a way to circumvent the ban on Sino-Japanese trade. The Chinese bought deerskins from the aborigines and sold them to the Japanese for a large profit.[105]

When a Portuguese ship sailed past southwestern Taiwan in 1596, several of its crew members who had been shipwrecked there in 1582 noticed that the land had become cultivated and now had people working it, presumably by settlers from Fujian.[106] When the Dutch arrived in 1623, they found about 1,500 Chinese visitors and residents. Most of them were engaged in seasonal fishing, hunting, and trading. The population fluctuated throughout the year peaking during winter. A small minority brought Chinese plants with them and grew crops such as apples, oranges, bananas, watermelons.[107] Some estimates of the Chinese population put it at 2,000.[100] There were two Chinese villages. The larger one was located on an island that formed the Bay of Tayouan. It was inhabited year-round. The smaller village was located on the mainland and would eventually become the city of Tainan. In the early 17th century, a Chinese man described it as being inhabited by pirates and fishermen. One Dutch visitor noted that an aboriginal village near the Sino-Japanese trade center had a large number of Chinese and there was "scarcely a house in this village . . . that does not have one or two or three, or even five or six Chinese living there."[105] The villagers' speech contained many Chinese words and sounded like "a mixed and broken language."[105]

Chen Di visited Taiwan in 1603 on an expedition against the Wokou pirates.[108][109] General Shen of Wuyu defeated the pirates and met a native chieftain named Damila who presented them with gifts.[110] Chen witnessed these events and wrote an account of Taiwan known as Dongfanji (An Account of the Eastern Barbarians).[111] According to Chen, Zheng He visited the natives but they remained hidden. Afterwards they came into contact with Chinese people from the harbors of Huimin, Chonglong, and Lieyu in Zhangzhou and Quanzhou. They learned their languages to trade with them. Chinese items such as agate beads, porcelain, cloth, salt, and brass were traded in return for deer meat, skins, and horns.[112]

European period (1623–1662)

During the European period (1623–1662) soldiers and traders representing the Dutch East India Company maintained a colony in southwestern Taiwan (1624–1662) near present-day Tainan. This established an Asian base for triangular trade between the company, the Qing dynasty and Japan, with the hope of interrupting Portuguese and Spanish trading alliances with China. The Spanish also established a small colony in northern Taiwan (1626–1642) in present-day Keelung. However, Spanish influence wavered almost from the beginning, so that by the late 1630s they had already withdrawn most of their troops.[113] After they were driven out of Taiwan by a combined Dutch and aboriginal force in 1642, the Spanish "had little effect on Taiwan's history".[114] Dutch influence was far more significant: expanding to the southwest and north of the island, they set up a tax system and established schools and churches in many villages.

When the Dutch arrived in 1624 at Tayouan (Anping) Harbor, Siraya-speaking representatives from nearby Saccam village soon appeared at the Dutch stockade to barter and trade; an overture which was readily welcomed by the Dutch. The Sirayan villages were, however, divided into warring factions: the village of Sinckan (Sinshih) was at war with Mattau (Madou) and its ally Baccluan, while the village of Soulang maintained uneasy neutrality. In 1629 a Dutch expeditionary force searching for Han pirates was massacred by warriors from Mattau, and the victory inspired other villages to rebel.[115] In 1635, with reinforcements having arrived from Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia), the Dutch subjugated and burned Mattau. Since Mattau was the most powerful village in the area, the victory brought a spate of peace offerings from other nearby villages, many of which were outside the Siraya area. This was the beginning of Dutch consolidation over large parts of Taiwan, which brought an end to centuries of inter-village warfare.[116] The new period of peace allowed the Dutch to construct schools and churches aimed to acculturate and convert the indigenous population.[117][118] Dutch schools taught a romanized script (Sinckan writing), which transcribed the Siraya language. This script maintained occasional use through the 18th century.[119] Today only fragments survive, in documents and stone stele markers. The schools also served to maintain alliances and open aboriginal areas for Dutch enterprise and commerce.

The Dutch soon found trade in deerskins and venison in the East Asian market to be a lucrative endeavor[120] and recruited plains indigenous peoples to procure the hides. The deer trade attracted the first Han traders to indigenous villages, but as early as 1642 the demand for deer greatly diminished the deer stocks. This drop significantly reduced the prosperity of indigenous peoples,[121] forcing many aborigines to take up farming to counter the economic impact of losing their most vital food source.

As the Dutch began subjugating indigenous villages in the south and west of Taiwan, increasing numbers of Han immigrants looked to exploit areas that were fertile and rich in game. The Dutch initially encouraged this, since the Han were skilled in agriculture and large-scale hunting. Several Han took up residence in Siraya villages. The Dutch used Han agents to collect taxes, hunting license fees and other income. This set up a society in which "many of the colonists were Han Chinese but the military and the administrative structures were Dutch".[122] Despite this, local alliances transcended ethnicity during the Dutch period. For example, the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion in 1652, a Han farmers' uprising, was defeated by an alliance of 120 Dutch musketeers with the aid of Han loyalists and 600 indigenous warriors.[123]

Multiple indigenous villages in frontier areas rebelled against the Dutch in the 1650s due to oppression such as when the Dutch ordered indigenous women for sex, deer pelts, and rice be given to them from indigenous in the Taipei Basin in Wu-lao-wan village which sparked a rebellion in December 1652 at the same time as the Chinese rebellion. Two Dutch translators were beheaded by the Wu-lao-wan indigenous people and in a subsequent fight, 30 indigenous and another two Dutch people died. After an embargo of salt and iron on Wu-lao-wan, the indigenous people were forced to sue for peace in February 1653.[124]

The Dutch period ended in 1662 when Ming loyalist forces of Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga) drove out the Dutch and established the short-lived Zheng family kingdom on Taiwan. Dutch colonialism left different impressions on different indigenous groups in Taiwan. The Koaluts (Guizaijiao) tribe of the Paiwan people attacked American survivors of a shipwreck during the Rover incident in 1867. The chief, Tanketok, explained that this was because in ages past, the white men came and almost exterminated their tribe, and their ancestors passed down their desire for revenge.[125] According to William A. Pickering in his Pioneering in Formosa (1898), the old people of Kong-a-na, about 15 miles from Sin-kang, loved white men and the old women there said they were their kindred.[126][non-primary source needed]

Kingdom of Tungning (1661–1683)

The Kingdom of Tungning was established by Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga) after arriving in Taiwan in 1661 and ousting the Dutch in 1662. The Taiwanese indigenous tribes who were previously allied with the Dutch against the Chinese during the Guo Huaiyi rebellion in 1652 turned against the Dutch during the Siege of Fort Zeelandia and defected to Koxinga's Chinese forces.[127] The aboriginals of Sincan defected to Koxinga after he offered them amnesty. The Sincan indigenous people then proceeded to work for the Chinese and behead Dutch people in executions. The frontier indigenous in the mountains and plains also surrendered and defected to the Chinese on 17 May 1661, celebrating their freedom from compulsory education under the Dutch rule by hunting down Dutch people and beheading them and trashing their Christian school textbooks.[128]

Koxinga's son and successor, Zheng Jing, dispatched teachers to indigenous tribes to provide them with supplies and teach them more advanced farming techniques. He also gave them Ming gowns and caps while eating with their chiefs and gifting tobacco to indigenous people who were gathered in crowds to meet and welcome him as he visited their villages after he defeated the Dutch.[129] Schools were set up to teach the indigenous people the Chinese language, writing, and the Confucian Classics.[130] Those who refused were punished.[131][129]

Zhengs brought 70,000 soldiers to Taiwan and immediately began clearing large tracts of land to support its forces.[130] The expansion of Chinese settlements often came at the expense of aboriginal tribes, causing rebellions flared up over the course of Zheng rule. In one campaign, several hundred Shalu tribes people in modern Taichung were killed.[129][132] By the start of 1684, a year after the end of Zheng rule, areas under cultivation in Taiwan had tripled in size since the end of the Dutch era in 1660.[132]

Qing dynasty rule (1683–1895)

Quarantine policies

After the Qing dynasty government defeated the Ming loyalist forces maintained by the Zheng family in 1683, Taiwan became increasingly integrated into the Qing dynasty.[133] Qing forces ruled areas of Taiwan's highly populated western plain for over two centuries, until 1895. This era was characterized by a marked increase in the number of Han Chinese on Taiwan, continued social unrest, the piecemeal transfer (by various means) of large amounts of land from the indigenous to the Han, and the nearly complete acculturation of the Western Plains indigenous people to Chinese Han customs.

During the Qing dynasty's two-century rule over Taiwan, the population of Han on the island increased dramatically. However, it is not clear to what extent this was due to an influx of Han settlers, who were predominantly displaced young men from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou in Fujian province.[134] The Qing government officially sanctioned controlled Han settlement, but sought to manage tensions between the various regional and ethnic groups. Therefore, it often recognized the plains peoples' claims to deer fields and traditional territory.[135][136] The Qing authorities hoped to turn the Plains peoples into loyal subjects, and adopted the head and corvée taxes on the indigenous, which made the plains indigenous people directly responsible for payment to the government yamen. The attention paid by the Qing authorities to indigenous land rights was part of a larger administrative goal to maintain a level of peace on the turbulent Taiwan frontier, which was often marred by ethnic and regional conflict.[137] The frequency of rebellions, riots, and civil strife in Qing dynasty Taiwan is often encapsulated in the saying "every three years an uprising; every five years a rebellion".[138]

In 1723, aborigines living in Dajiaxi village along the central coastal plain rebelled. Government troops from southern Taiwan were sent to put down this revolt, but in their absence, Han settlers in Fengshan County rose up in revolt under the leadership of Wu Fusheng, a settler from Zhangzhou.[139] Indigenous participation in major revolts during the Qing era, including the Taokas-led Ta-Chia-hsi revolt of 1731–1732, ensured the Plains peoples would remain an important factor in crafting Qing frontier policy until the end of Qing rule in 1895.[140] By 1732, five different ethnic groups were in revolt but the rebellion was defeated by the end of the year.[139]

The struggle over land resources was one source of conflict. Large areas of the western plain were subject to large land rents called Huan Da Zu (番大租—literally, "Barbarian Big Rent"), a category which remained until the period of Japanese colonization. The large tracts of deer field, guaranteed by the Qing, were owned by the communities and their individual members. The communities would commonly offer Han farmers a permanent patent for use, while maintaining ownership (skeleton) of the subsoil (田骨), which was called "two lords to a field" (一田兩主). The Plains peoples were often cheated out of land or pressured to sell at unfavorable rates. Some disaffected subgroups moved to central or eastern Taiwan, but most remained in their ancestral locations and acculturated or assimilated into Han society.[141][page needed] Despite this, the vast majority of rebellions did not originate from indigenous peoples but the Han settlers, and the mountain aborigines were left to their own devices until the last 20 years of Qing rule.[142] During the Qianlong period (1735–1796), the 93 shufan acculturated aborigine villages never rebelled and over 200 non-acculturated aboriginal villages submitted.[143]

During the reigns of the Kangxi (r. 1661–1722), Yongzheng (r. 1722–1735), and Qianlong (r. 1735–1796) emperors, the Qing court deliberately restricted the expansion of territory and government administration in Taiwan. A government permit was required for settlers to go beyond the Dajia River at the mid-point of the western plains. In 1715, the governor-general of Fujian-Zhejiang recommended land reclamation in Taiwan but Kangxi was worried that this would cause instability and conflicts. By the time of Yongzheng's reign, the Qing extended control over the entire western plains, but this was to better control the settlers and maintain security. The quarantine policies were maintained. After the Zhu Yigui uprising which occurred in 1721, Lan Dingyuan, an advisor to Lan Tingzhen, who led forces against the rebellion, advocated for expansion and land reclamation to strengthen government control over the Chinese settlers. He wanted to convert the aborigines to Han culture and turn them into subjects of the Qing. However, the Qianlong Emperor kept the administrative structure of Taiwan largely unchanged and in 1744, he dismissed recommendations by officials to allow settlers to claim land.[144]

Qing classification of indigenous peoples

The Qing did little to administer the indigenous and rarely tried to subjugate or impose cultural change upon them. Indigenous peoples were classified into two general categories: acculturated aborigines (shufan) and non-acculturated aborigines (shengfan). Sheng is a word used to describe uncooked food, unworked land, unripened-fruit, unskilled labor or strangers, while shu bears the opposite meaning. To the Qing, shufan were indigenous who paid taxes, performed corvée, and had adopted Han Chinese culture to some degree. When the Qing annexed Taiwan, there were 46 indigenous villages under government control: 12 in Fengshan and 34 in Zhuluo. These were likely inherited from the Zheng regime. In the Yongzheng period, 108 indigenous villages submitted as a result of encouragement and enticement from the Taiwan regional commander, Lin Liang. Shengfan who paid taxes but did not perform corvée and did not practice Han Chinese culture were called guihua shengfan (submitted non-acculturated aborigines).[145]

The Qianlong administration forbade enticing indigenous to submit due to fear of conflict. In the early Qianlong period, there were 299 named indigenous villages. Records show 93 shufan villages and 61 guihua shengfan villages. The number of shufan villages remained stable throughout the Qianlong period. Two indigenous affairs sub-prefects were appointed to manage aboriginal affairs in 1766. One was in charge of the north and the other in charge of the south, both focused on the plains aborigines. Boundaries were built to keep the mountain indigenous people out of settlement areas. The policy of marking settler boundaries and segregating them from indigenous territories became official policy in 1722 in response to the Zhu Yigui uprising. Fifty-four stelae were used to mark crucial points along the settler-indigenous boundary. Han settlers were forbidden from crossing into indigenous territory but settler encroachment continued, and the boundaries were rebuilt in 1750, 1760, 1784, and 1790. Settlers were forbidden from marrying indigenous as marriage was one way settlers obtained land. While the settlers drove colonization and acculturation, the Qing policy of quarantine dented the impact on aborigines, especially mountain indigenous people.[146]

Settler expansion

Although Qing quarantine policies were maintained in the early 19th century, attitudes towards indigenous territories started to shift. Local officials repeatedly advocated for the colonization of indigenous territories, especially in the cases of Gamalan and Shuishalian. The Gamalan or Kavalan people were situated in modern Yilan County in northeastern Taiwan. It was separated from the western plains and Tamsui (Danshui) by mountains. There were 36 indigenous villages in the area and the Kavalan people had started paying taxes as early as the Kangxi period (r. 1661–1722), but they were non-acculturated guihua shengfan aborigines.[147]

In 1787, a Chinese settler named Wu Sha tried to reclaim land in Gamalan but was defeated by indigenous people. The next year, the Tamsui sub-prefect convinced the Taiwan prefect, Yang Tingli, to support Wu Sha. Yang recommended subjugating the natives and opening Gamalan for settlement to the Fujian governor but the governor refused to act due to fear of conflict. In 1797, a new Tamsui sub-prefect issued permit and financial support for Wu to recruit settlers for land reclamation, which was illegal. Wu's successors were unable to register the reclaimed land on government registers. Local officials supported land reclamation but could not officially recognize it.[148]

In 1806 it was reported that a pirate, Cai Qian, was within the vicinity of Gamalan. Taiwan Prefect Yang once again recommended opening up Gamalan, arguing that to abandon it would cause trouble on the frontier. Later another pirate band tried to occupy Gamalan. Yang recommended to the Fuzhou General Saichong'a the establishment of administration and land surveys in Gamalan. Saichong'a initially refused but then changed his mind and sent a memorial to the emperor in 1808 recommending the incorporation of Gamalan. The issue was discussed by the central government officials and for the first time, one official went on record saying that if aboriginal territory was incorporated, not only would it end the pirate threat but the government would stand to profit from the land itself. In 1809, the emperor ordered for Gamalan to be incorporated. The next year an imperial decree for the formal incorporation of Gamalan was issued and a Gamalan sub-prefect was appointed.[149]

Unlike Gamalan, debates on Shuishalian resulted in its continued status as a closed-off area. Shuishalian refers to the upstream areas of the Zhuoshui River and Wu River in central Taiwan. The inner mountain area of Shuishalian was inhabited by 24 indigenous villages and six of them occupied the flat and fertile basin area. The indigenous had submitted as early as 1693 but they remained non-acculturated. In 1814, some settlers were able to obtain reclamation permits through fabricating aboriginal land lease requests. In 1816, the government sent troops to evict the settlers and destroy their strongholds. Stelae were erected demarcating the land forbidden to Chinese settlers.[150]

Local officials advocated for supporting colonization efforts into the mid-1800s but their recommendations were ignored.[151]

Migration to highlands

One popular narrative holds that all of the Gaoshan peoples were originally Plains peoples, which fled to the mountains under pressure from Han encroachment. This strong version of the "migration" theory has been largely discounted by contemporary research as the Gaoshan people demonstrate a physiology, material cultures and customs that have been adapted for life at higher elevations. Linguistic, archeological, and recorded anecdotal evidence also suggests there has been island-wide migration of indigenous peoples for over 3,000 years.[152]

Small sub-groups of Plains Indigenous Peoples may have occasionally fled to the mountains, foothills or eastern plain to escape hostile groups of Han or other aborigines.[153][154] The "displacement scenario" is more likely rooted in the older customs of many Plains groups to withdraw into the foothills during headhunting season or when threatened by a neighboring village, as observed by the Dutch during their punitive campaign of Mattou in 1636 when the bulk of the village retreated to Tevorangh.[155][156][157] The "displacement scenario" may also stem from the inland migrations of Plains indigenous subgroups, who were displaced by either Han or other Plains indigenous and chose to move to the Iilan plain in 1804, the Puli basin in 1823 and another Puli migration in 1875. Each migration consisted of a number of families and totaled hundreds of people, not entire communities.[158][159] There are also recorded oral histories that recall some Plains indigenous people were sometimes captured and killed by Highlands peoples while relocating through the mountains.[160] However, as Shepherd (1993) explained in detail, documented evidence shows that the majority of Plains people remained on the plains, intermarried Hakka and Hoklo immigrants from Fujian and Guangdong, and adopted a Han identity.

Colonization in reaction to crises

In 1874, Japan invaded indigenous territory in southern Taiwan in what is known as the Mudan Incident (Japanese invasion of Taiwan (1874)). For six months Japanese soldiers occupied southern Taiwan and Japan argued that it was not part of the Qing dynasty. The result was the payment of an indemnity by the Qing in return for the Japanese army's withdrawal.[161]

The imperial commissioner for Taiwan, Shen Baozhen, argued that "the reason that Taiwan is being coveted by is that the land is too empty."[162] He recommended subjugating the indigenous and populating their territory with Chinese settlers. As a result, the administration of Taiwan was expanded and campaigns against the indigenous were launched. The two sub-prefects responsible for indigenous affairs were moved to inner Shushalian (Puli) and eastern Taiwan (Beinan), the focal points for colonization. Starting in 1874, mountain roads were built to make the region more accessible and indigenous people were brought into formal submission to the Qing. In 1875, the ban on entering Taiwan was lifted.[162] In 1877, 21 guidelines on subjugating indigenous peoples and opening the mountains were issued. Agencies for recruiting settlers were established on the coastal mainland and in Hong Kong. However efforts to promote settlement in Taiwan petered out soon after.[163]

Efforts to settle in indigenous territories were renewed under the governance of Liu Mingchuan after the Sino-French War ended in 1885.[164] However few settlers went to Taiwan and those that did were accosted by aborigines and the harsh climate. Governor Liu was criticized for the high cost and little gain from the colonization activities. Liu resigned in 1891 and the colonization efforts ceased.[165]

A Taiwan Pacification and Reclamation Head Office was established with eight pacification and reclamation bureaus. Four bureaus were located in eastern Taiwan, two in Puli (inner Shuishalian), one in the north, and one on the western border of the mountains. By 1887, about 500 indigenous villages, or roughly 90,000 indigenous had formally submitted to Qing rule. This number increased to 800 villages with 148,479 indigenous over the following years. However the cost of getting them to submit was exorbitant. The Qing offered them materials and paid village chiefs monthly allowances. Not all the indigenous were under effective control and land reclamation in eastern Taiwan occurred at a slow pace.[165] From 1884 to 1891, Liu launched more than 40 military campaigns against the aborigines with 17,500 soldiers. A third of the invasion force was killed or disabled in the conflict, amounting to a costly failure.[166]

By the end of the Qing period, the western plains were fully developed as farmland with about 2.5 million Chinese settlers. The mountainous areas were still largely autonomous under the control of indigenous. Indigenous land loss under the Qing occurred at a relatively slow pace compared to the following Japanese colonial period due to the absence of state sponsored land deprivation for the majority of Qing rule.[167][168] In the 50-year period of Japanese rule that followed, the Taiwanese aborigines lost their right to legal ownership of land and were confined to small reserves one-eighth the size of their ancestral lands.[169] However even had Japan not taken over Taiwan, the plains indigenous were on the way to losing their residual rights to land. By the last years of Qing rule, most of the plains aborigines had been acculturated to Han culture, around 20–30% could speak their mother tongues, and gradually lost their land ownership and rent collection rights.[170]

Highland peoples

Imperial Chinese and European societies had little contact with the Highland indigenous until expeditions to the region by European and American explorers and missionaries commenced in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[171][172] The lack of data before this was primarily the result of a Qing quarantine on the region to the east of the "earth oxen" (土牛) border, which ran along the eastern edge of the western plain. Han contact with the mountain peoples was usually associated with the enterprise of gathering and extracting camphor from Camphor Laurel trees (Cinnamomum camphora), native to the island and in particular the mountainous areas. The production and shipment of camphor (used in herbal medicines and mothballs) was then a significant industry on the island, lasting up to and including the period of Japanese rule.[173] These early encounters often involved headhunting parties from the Highland peoples, who sought out and raided unprotected Han forest workers. Together with traditional Han concepts of Taiwanese behavior, these raiding incidents helped to promote the Qing-era popular image of the "violent" aborigine.[174]

Taiwanese Plains indigenous were often employed and dispatched as interpreters to assist in the trade of goods between Han merchants and Highlands aborigines. The indigenous people traded cloth, pelts and meat for iron and matchlock rifles. Iron was a necessary material for the fabrication of hunting knives—long, curved sabers that were generally used as a forest tool. These blades became notorious among Han settlers, given their alternative use to decapitate Highland indigenous enemies in customary headhunting expeditions.[citation needed]

Headhunting

Every tribe except the Tao people of Orchid Island practiced headhunting, which was a symbol of bravery and valor.[175] Men who did not take heads could not cross the rainbow bridge into the spirit world upon death as per the religion of Gaya. Each tribe has its own origin story for the tradition of headhunting but the theme is similar across tribes. After the great flood, headhunting originated due to boredom (South Tsou Sa'arua, Paiwan), to improve tribal singing (Ali Mountain Tsou), as a form of population control (Atayal, Taroko, Bunun), simply for amusement and fun (Rukai, Tsou, Puyuma) or particularly for the fun and excitement of killing intellectually disabled individuals (Amis). Once the victims had been decapitated and displayed the heads were boiled and left to dry, often hanging from trees or displayed on slate shelves referred to as "skull racks". A party returning with a head was cause for celebration, as it was believed to bring good luck and the spiritual power of the slaughtered individual was believed to transfer into the headhunter. If the head was that of a woman it was even better because it meant she could not bear children. The Bunun people would often take prisoners and inscribe prayers or messages to their dead on arrows, then shoot their prisoner with the hope their prayers would be carried to the dead. Taiwanese Hoklo Han settlers and Japanese were often the victims of headhunting raids as they were considered by the indigenous to be liars and enemies. A headhunting raid would often strike at workers in the fields, or set a dwelling alight and then decapitate the inhabitants as they fled the burning structure. It was also customary to later raise the victim's surviving children as full members of the community. Often the heads themselves were ceremonially 'invited' to join the community as members, where they were supposed to watch over the community and keep them safe. The indigenous inhabitants of Taiwan accepted the convention and practice of headhunting as one of the calculated risks of community life. The last groups to practice headhunting were the Paiwan, Bunun, and Atayal groups.[176] Japanese rule ended the practice by 1930, (though Japanese were not subject to this regulation and continued to headhunt their enemies throughout World War II) and as late as 2003 there are elder Taiwanese that could recall the practice firsthand.[177]

Japanese rule (1895–1945)edit

When the Treaty of Shimonoseki was finalized on 17 April 1895, Taiwan was ceded by the Qing Empire to Japan.[178] Taiwan's incorporation into the Japanese political orbit brought Taiwanese indigenous into contact with a new colonial structure, determined to define and locate indigenous people within the framework of a new, multi-ethnic empire.[179] The means of accomplishing this goal took three main forms: anthropological study of the natives of Taiwan, attempts to reshape the indigenous in the mold of the Japanese, and military suppression. The indigenous and Han joined to violently revolt against Japanese rule in the 1907 Beipu Uprising and 1915 Tapani Incident.

Japan's sentiment regarding indigenous peoples was crafted around the memory of the Mudan Incident, when, in 1871, a group of 54 shipwrecked Ryūkyūan sailors was massacred by a Paiwan group from the village of Mudan in southern Taiwan. The resulting Japanese policy, published twenty years before the onset of their rule on Taiwan, cast Taiwanese indigenous as "vicious, violent and cruel" and concluded "this is a pitfall of the world; we must get rid of them all".[180] Japanese campaigns to gain aboriginal submission were often brutal, as evidenced in the desire of Japan's first Governor General, Kabayama Sukenori, to "...conquer the barbarians" (Kleeman 2003:20). The Seediq indigenous fought against the Japanese in multiple battles such as the Xincheng incident (新城事件), Truku battle (太魯閣之役) (Taroko),[181] 1902 Renzhiguan incident (人止關事件), and the 1903 Zimeiyuan incident (姊妹原事件). In the Musha Incident of 1930, for example, a Seediq group was decimated by artillery and supplanted by the Taroko (Truku), which had sustained periods of bombardment from naval ships and airplanes dropping mustard gas. A quarantine was placed around the mountain areas enforced by armed guard stations and electrified fences until the most remote high mountain villages could be relocated closer to administrative control.[182]

A divide and rule policy was formulated with Japan trying to play indigenous and Han against each other to their own benefit when Japan alternated between fighting the two with Japan first fighting Han and then fighting indigenous.[183] Nationalist Japanese claim indigenous were treated well by Kabayama.[184] unenlightened and stubbornly stupid were the words used to describe indigenous by Kabayama Sukenori.[185] A hardline anti indigenous position aimed at the destruction of their civilization was implemented by Fukuzawa Yukichi.[186] The most tenacioius opposition was mounted by the Bunan and Atayal against the Japanese during the brutal mountain war in 1913–14 under Sakuma. Indigenous continued to fight against the Japanese after 1915.[187] Aboriginals were subjected to military takeover and assimilation.[188] In order to exploit camphor resources, the Japanese fought against the Bngciq Atayal in 1906 and expelled them.[189][190] The war is called "Camphor War" (樟腦戰爭).[191][192]

The Bunun indigenous under Chief Raho Ari (or Dahu Ali, 拉荷·阿雷, lāhè āléi) engaged in guerilla warfare against the Japanese for twenty years. Raho Ari's revolt was sparked when the Japanese implemented a gun control policy in 1914 against the indigenous people in which their rifles were impounded in police stations when hunting expeditions were over. The Dafen incident w:zh:大分事件 began at Dafen when a police platoon was slaughtered by Raho Ari's clan in 1915. A settlement holding 266 people called Tamaho was created by Raho Ari and his followers near the source of the Laonong River and attracted more Bunun rebels to their cause. Raho Ari and his followers captured bullets and guns and slew Japanese in repeated hit and run raids against Japanese police stations by infiltrating over the Japanese "guardline" of electrified fences and police stations as they pleased.[193]

The 1930 "New Flora and Silva, Volume 2" said of the mountain indigenous that the "majority of them live in a state of war against Japanese authority".[194] The Bunun and Atayal were described as the "most ferocious" indigenous people, and police stations were targeted by indigenous in intermittent assaults.[195] By January 1915, all indigenous peoples in northern Taiwan were forced to hand over their guns to the Japanese, however head hunting and assaults on police stations by indigenous still continued after that year.[195][196] Between 1921 and 1929 Aboriginal raids died down, but a major revival and surge in Aboriginal armed resistance erupted from 1930 to 1933 for four years during which the Musha Incident occurred and Bunun carried out raids, after which armed conflict again died down.[197] According to a 1933-year book, wounded people in the Japanese war against the Aboriginals numbered around 4,160, with 4,422 civilians dead and 2,660 military personnel killed.[198] According to a 1935 report, 7,081 Japanese were killed in the armed struggle from 1896 to 1933 while the Japanese confiscated 29,772 indigenous people's guns by 1933.[199]

Beginning in the first year of Japanese rule, the colonial government embarked on a mission to study the indigenous so they could be classified, located and "civilized". The Japanese "civilizing project", partially fueled by public demand in Japan to know more about the empire, would be used to benefit the Imperial government by consolidating administrative control over the entire island, opening up vast tracts of land for exploitation.[200] To satisfy these needs, "the Japanese portrayed and catalogued Taiwan's indigenous peoples in a welter of statistical tables, magazine and newspaper articles, photograph albums for popular consumption".[201] The Japanese based much of their information and terminology on prior Qing era narratives concerning degrees of "civilization".[202]

Japanese ethnographer Ino Kanori was charged with the task of surveying the entire population of Taiwanese indigenous, applying the first systematic study of aborigines on Taiwan. Ino's research is best known for his formalization of eight peoples of Taiwanese aborigines: Atayal, Bunun, Saisiat, Tsou, Paiwan, Puyuma, Ami and Pepo (Pingpu).[203][204] This is the direct antecedent of the taxonomy used today to distinguish people groups that are officially recognized by the government.

Life under the Japanese changed rapidly as many of the traditional structures were replaced by a military power. Indigenous people who wished to improve their status looked to education rather than headhunting as the new form of power. Those who learned to work with the Japanese and follow their customs would be better suited to lead villages. The Japanese encouraged aborigines to maintain traditional costumes and selected customs that were not considered detrimental to society, but invested much time and money in efforts to eliminate traditions deemed unsavory by Japanese culture, including tattooing.[205] By the mid-1930s as Japan's empire was reaching its zenith, the colonial government began a political socialization program designed to enforce Japanese customs, rituals and a loyal Japanese identity upon the aborigines. By the end of World War II, aborigines whose fathers had been killed in pacification campaigns were volunteering to serve in Special Units and if need be die for the Emperor of Japan.[206] The Japanese colonial experience left an indelible mark on many older aborigines who maintained an admiration for the Japanese long after their departure in 1945.[207]

The Japanese troops used indigenous women as sex slaves, so called "comfort women".[208]

Kuomintang single-party rule (1945–1987)edit

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Taiwanese_indigenous_peoplesText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk