A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

European Union citizenship is afforded to all nationals of member states of the European Union (EU). It was formally created with the adoption of the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, at the same time as the creation of the EU. EU citizenship is additional to, as it does not replace, national citizenship.[1][2] It affords EU citizens with rights, freedoms and legal protections available under EU law.

EU citizens have freedom of movement, and the freedom of settlement and employment across the EU. They are free to trade and transport goods, services and capital through EU state borders, with no restrictions on capital movements or fees.[3] EU citizens have the right to vote and run as a candidate in certain (often local) elections in the member state where they live that is not their state of origin, while also voting for EU elections and participating in a European Citizens' Initiative (ECI).

Citizenship of the EU confers the right to consular protection by embassies of other EU member states when an individual's country of citizenship is not represented by an embassy or consulate in the foreign country in which they require protection or other types of assistance.[4] EU citizens have the right to address the European Parliament, the European Ombudsman and EU agencies directly, in any of the EU Treaty languages,[5] provided the issue raised is within that institution's competence.[6]

EU citizens have the legal protections of EU law,[7] including the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU[8] and acts and directives regarding protection of personal data, rights of victims of crime, preventing and combating trafficking in human beings, equal pay, as well as protection from discrimination in employment on grounds of religion or belief, sexual orientation and age.[8][9] The office of the European Ombudsman can be directly approached by EU citizens.[10]

History

The modern EU citizenship status partially relies on the millennia of European history and Europe's common cultural heritage.[11] "The introduction of a European form of citizenship with precisely defined rights and duties was considered as long ago as the 1960s",[12] but the roots of "the key rights of EU citizenship—primarily the right to live and the right to work anywhere within the territory of the Member States—can be traced back to the free movement provisions contained in the Treaty of Paris establishing the European Coal and Steel Community, which entered into force in 1952."[13] The Treaty of Paris introduced freedom of movement for the professionals in the coal and steel industry which may be considered the nascent form of free movement that developed into EU citizenship four decades later.[11] The citizenship of the European Union was first introduced by the Maastricht Treaty, and was extended by the Treaty of Amsterdam.[14] Prior to the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, the European Communities treaties provided guarantees for the free movement of economically active People, but not, generally, for others. The 1951 Treaty of Paris[15] establishing the European Coal and Steel Community established a right to free movement for workers in these industries and the 1957 Treaty of Rome[16] provided for the free movement of workers and services. However, we can find traces of an emerging European personal status in the legal framework regulating the rights and obligations of foreign residents in Europe well before a formal status of European citizenship was introduced. In particular through the interplay between secondary European legislation and the case-law of the European Court of Justice. This formed an embryo of the future European Citizenship,[17] and came to be defined by the practice of freedom of movement of workers within the newly established European Economic Community.

The rights of an "embryonic"[13] European citizenship have been developed by the European Court of Justice well before the formal institution of European citizenship by the Maastricht Treaty.[18] This could happen after the two landmark decisions in the cases Van Gend en Loos[19] and Costa/ENEL,[20] which established (a) the principle of direct effect of EEC law, and (b) the supremacy of European law over national law, including the constitutional one. In particular, the 1957 Rome Treaty[21] provisions were interpreted by the European Court of Justice not as having a narrow economic purpose, but rather a wider social and economic one.[22]

The rights associated with the European Personal Status were firstly recognized "to certain categories of workers, then expanded to all workers, to certain categories of non-workers (e.g. retirees, students), and finally perhaps to all citizens".[13] In line with the model of social citizenship proposed by Thomas Humphrey Marshall, the "European Personal Status" or "Proto-European citizenship"[17] was built by recognizing the social rights connected to freedom of movement[21] and freedom of establishment in the first years of the EEC, when workers' rights in the host state were progressively extended to their family members even beyond the status of "worker",[23][24][25][26][27] so as to promote the full social integration of the workers and their families in the host member state.[28]

When Regulation 1612/68[29] abolished movement and residence restrictions for member state workers and their families in the entire EEC territory, thus ending the transitional period established by article 49 of the Rome Treaty,[30] not only this created the conditions for a full exercise of free movement rights, but a number of important new rights were subsequently recognized by the ECJ, such as: the right to a minimum wage in the host state,[31] the reduction of fares on public transport for large families,[32] the right to a check for disabled adults,[33] interest-free loans for the birth of children,[34] the right to reside with a non-spousal partner,[35] the payment of funeral expenses.[36]

As later stated in Levin,[37] the Court found that the "freedom to take up employment was important, not just as a means towards the creation of a single market for the benefit of the member state economies, but as a right for the worker to raise her or his standard of living".[22] Under the ECJ case-law, the rights of free movement of workers applies regardless of the worker's purpose in taking up employment abroad,[37] to both part-time and full-time work,[37] and whether or not the worker required additional financial assistance from the member state into which he moves.[38]

Before the institution of the European citizenship the ECJ interpreted the status of "worker" it beyond its purely literal meaning, progressively extending it to subjects such as non-economically active family members, students, tourists.[39] This led the Court to hold that a mere recipient of services has free movement rights under the Treaty,[40] so that almost every national of an EU country moving to another member state as a recipient of services, whether economically active or not, but provided they do not constitute an unreasonable burden for the host state, shall non be granted equality of treatment[41] had a right to non-discrimination on the ground of nationality even prior to the Maastricht Treaty.[42]

The Maastricht Treaty dispositions on the status of European citizenship (having direct effect, i.e. directly conferring the status of European citizen to all member states nationals) were not immediately applied by the Court, which continued following the previous interpretative approach and employed European citizenship as a supplementary argument in order to confirm and consolidate precedent law.[43] It was only a few years after the entry into force of the Treaty of Maastricht that the Court finally decided to abandon this approach and to recognize the status of European citizen in order to decide the controversies. Two landmark decisions in this sense are Martinez Sala,[44] and Grelczyk.[45]

On the one hand, citizenship has an inclusive character, as it allows its holders freedoms and encourages and enables active participation and active use of these rights. On the other hand, and the following is not meant to diminish this first fact, the inclusion of a certain group results in the differentiation of others. Only through active differentiation and demarcation, i.e. exclusion, an identity with formal criteria can be created.

Due to the history of the EU and its mentioned development, the progress of including and excluding is inevitably full of tensions. Many dynamics in citizenship grounded in the tension between the formal law part and the non-/beyond-law surrounding; such as the enlargement of freedom and rights to every kind of explicitly or implicitly economically active persons. Homeless and poor people do not enjoy these freedoms, because of a lack of economic action. The situation is the same when the home state says someone might no longer enjoy these rights.

Economically inactive EU citizens who want to stay longer than three months in another Member State have to fulfill the condition of having health insurance and "sufficient resources" in order not to become an "unreasonable burden" for the social assistance system of the host Member State, which otherwise can legitimately expel them.[46]

Stated rights

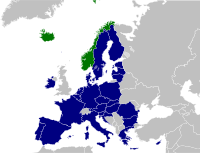

The rights of EU Citizens are enumerated in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and the Charter of Fundamental Rights.[48] Historically, the main benefit of being a citizen of an EU state has been that of free movement. The free movement also applies to the citizens of European Economic Area countries[49] and Switzerland.[50] However, with the creation of EU citizenship, certain political rights came into being.

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

The adoption of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR) enshrined specific political, social, and economic rights for EU citizens and residents. Title Five of the CFR focuses specifically on the rights of EU Citizens. Protected rights of EU citizens include the following:[51]

- The right to vote and to stand as a candidate at elections to the European Parliament.

- The right to vote and to stand as a candidate at municipal elections.

- The right to good administration.

- The right of access to documents.

- The right to petition.

- Freedom of movement and of residence.

- Diplomatic and consular protection.

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[52] provides for citizens to be "directly represented at Union level in the European Parliament" and "to participate in the democratic life of the Union" (Treaty on the European Union, Title II, Article 10). Specifically, the following rights are afforded:[1]

- Accessing European government documents: a right to access to documents of the EU government, whatever their medium. (Article 15).

- Freedom from any discrimination on nationality: a right not to be discriminated against on grounds of nationality within the scope of application of the Treaty (Article 18);

- Right to not be discriminated against: The EU government may take appropriate action to combat discrimination based on sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation (Article 19);

- Right to free movement and residence: a right of free movement and residence throughout the Union and the right to work in any position (including national civil services with the exception of those posts in the public sector that involve the exercise of powers conferred by public law and the safeguard of general interests of the State or local authorities (Article 21) for which however there is no one single definition);

- Voting in European elections: a right to vote and stand in elections to the European Parliament, in any EU member state (Article 22)

- Voting and running in municipal elections: a right to vote and stand in local elections in an EU state other than their own, under the same conditions as the nationals of that state (Article 22)

- Right to consular protection: a right to protection by the diplomatic or consular authorities of other Member States when in a non-EU Member State, if there are no diplomatic or consular authorities from the citizen's own state (Article 23)

- This is due to the fact that not all member states maintain embassies in every country in the world (some countries have only one embassy from an EU state).[53]

- Petitioning Parliament and the Ombudsman: the right to petition the European Parliament and the right to apply to the European Ombudsman to bring to his attention any cases of poor administration by the EU institutions and bodies, with the exception of the legal bodies (Article 24)[54]

- Language rights: the right to apply to the EU institutions in one of the official languages and to receive a reply in that same language (Article 24)

Free movement rights

- Article 21 Freedom to move and reside

Article 21 (1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[52] states that

Every citizen of the Union shall have the right to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States, subject to the limitations and conditions laid down in this Treaty and by the measures adopted to give it effect.

The European Court of Justice has remarked that,

EU Citizenship is destined to be the fundamental status of nationals of the Member States[55]

The ECJ has held that this Article confers a directly effective right upon citizens to reside in another Member State.[55][56] Before the case of Baumbast,[56] it was widely assumed that non-economically active citizens had no rights to residence deriving directly from the EU Treaty, only from directives created under the Treaty. In Baumbast, however, the ECJ held that (the then)[57] Article 18 of the EC Treaty granted a generally applicable right to residency, which is limited by secondary legislation, but only where that secondary legislation is proportionate.[58] Member States can distinguish between nationals and Union citizens but only if the provisions satisfy the test of proportionality.[59] Migrant EU citizens have a "legitimate expectation of a limited degree of financial solidarity... having regard to their degree of integration into the host society"[60] Length of time is a particularly important factor when considering the degree of integration.

The ECJ's case law on citizenship has been criticised for subjecting an increasing number of national rules to the proportionality assessment.[59] Also, the right to free movement is not fully available to certain groups of Union citizens because of the various hurdles they face in real life. For example, transgender EU citizens face problems getting identity documents and going through identity checks, reuniting with their family members and accompanying children, as well as accessing social assistance.[61] The scale of those issues gives grounds that only a limited form of EU citizenship is available to transgender people.[61]

- Article 45 Freedom of movement to work

Article 45 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[52] states that

- Freedom of movement for workers shall be secured within the Union.

- Such freedom of movement shall entail the abolition of any discrimination based on nationality between workers of the Member States as regards employment, remuneration and other conditions of work and employment.

State employment reserved exclusively for nationals varies between member states. For example, training as a barrister in Britain and Ireland is not reserved for nationals, while the corresponding French course qualifies one as a 'juge' and hence can only be taken by French citizens. However, it is broadly limited to those roles that exercise a significant degree of public authority, such as judges, police, the military, diplomats, senior civil servants or politicians. Note that not all Member States choose to restrict all of these posts to nationals.

Much of the existing secondary legislation and case law was consolidated[62] in the Citizens' Rights Directive 2004/38/EC on the right to move and reside freely within the EU.[63]

- Limitations

New member states may undergo transitional regimes for Freedom of movement for workers, during which their nationals only enjoy restricted access to labour markets in other member states. EU member states are permitted to keep restrictions on citizens of the newly acceded countries for a maximum of seven years after accession. For the EFTA states (Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway and Switzerland), the maximum is nine years.

Following the 2004 enlargement, three "old" member states—Ireland, Sweden and the United Kingdom—decided to allow unrestricted access to their labour markets. By December 2009, all but two member states—Austria and Germany—had completely dropped controls. These restrictions too expired on 1 May 2011.[64]

Following the 2007 enlargement, all pre-2004 member states except Finland and Sweden imposed restrictions on Bulgarian and Romanian citizens, as did two member states that joined in 2004: Malta and Hungary. As of November 2012, all but 8 EU countries have dropped restrictions entirely. These restrictions too expired on 1 January 2014. Norway opened its labour market in June 2012, while Switzerland kept restrictions in place until 2016.[64]

Following the 2013 enlargement, some countries implemented restrictions on Croatian nationals following the country's EU accession on 1 July 2013. As of March 2021, all EU countries have dropped restrictions entirely.[65][66][needs update]

Acquisition

There is no common EU policy on the acquisition of European citizenship as it is supplementary to national citizenship. (EC citizenship was initially granted to all nationals of European Community member states in 1994 by the Maastricht treaty concluded between the member states of the European community under international law, this changed into citizenship of the European Union in 2007 when the European Community changed its legal identity to be the European Union. Many more people became EU citizens when each new EU member state was added and, at each point, all the existing member states ratified the adjustments to the treaties to allow the creation of those extra citizenship rights for the individual. European citizenship is also generally granted at the same time as national citizenship is granted). Article 20 (1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[52] states that:

"Citizenship of the Union is hereby established. Every person holding the nationality of a Member State shall be a citizen of the Union. Citizenship of the Union shall be additional to and not replace national citizenship."

While nationals of Member States are citizens of the union, "It is for each Member State, having due regard to Union law, to lay down the conditions for the acquisition and loss of nationality."[67] As a result, there is a great variety in rules and practices with regard to the acquisition and loss of citizenship in EU member states.[68]

Exceptions for overseas territories

In practice this means that a member state may withhold EU citizenship from certain groups of citizens, most commonly in overseas territories of member states outside the EU.

A previous example was for the United Kingdom. Owing to the complexity of British nationality law, a 1982 declaration by Her Majesty's Government defined who would be deemed to be a British "national" for European Union purposes:[69]

- British citizens, as defined by Part I of the British Nationality Act 1981.

- British subjects, within the meaning of Part IV of the British Nationality Act 1981, but only if they also possessed the 'right of abode' under British immigration law.

- British overseas territories citizens who derived their citizenship by a connection to Gibraltar.

This declaration therefore excluded from EU citizenship various historic categories of British citizenship generally associated with former British colonies, such as British Overseas Citizens, British Nationals (Overseas), British protected persons and any British subject who did not have the 'right of abode' under British immigration law.

In 2002, with the passing of the British Overseas Territories Act 2002, EU citizenship was extended to almost all British overseas territories citizens when they were automatically granted full British citizenship (with the exception of those with an association to the British sovereign base areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia on the Island of Cyprus).[70] This had effectively granted them full EU citizenship rights, including free movement rights, although only residents of Gibraltar had the right to vote in European Parliament elections. In contrast, British citizens in the Crown Dependencies of Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man had always been considered to be EU citizens but, unlike residents of the British overseas territories, were prohibited from exercising EU free movement rights under the terms of the British Accession Treaty if they had no other connection with the UK (e.g. they had lived in the UK for five years, were born in the UK, or had parents or grandparents born in the UK) and had no EU voting rights. (see Guernsey passport, Isle of Man passport, Jersey passport).[71]

Another example are the residents of Faroe Islands of Denmark who, though in possession of full Danish citizenship, are outside the EU and are explicitly excluded from EU citizenship under the terms of the Danish Accession Treaty.[72] This is in contrast to residents of the Danish territory of Greenland who, whilst also outside the EU as a result of the 1984 Greenland Treaty, do receive EU citizenship as this was not specifically excluded by the terms of that treaty (see Faroe Islands and the European Union; Greenland and the European Union).

Greenland

Although Greenland withdrew from the European Communities in 1985, the autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark remains associated with the European Union, being one of the overseas countries and territories of the EU. The relationship with the EU means that all Danish citizens residing in Greenland are EU citizens. This allows Greenlanders to move and reside freely within the EU. This contrasts with Danish citizens living in the Faroe Islands who are excluded from EU citizenship.[73]

Summary of member states' nationality laws

This is a summary of nationality laws for each of the twenty-seven EU member states.[74]

| Member State | Acquisition by birth | Acquisition by descent | Acquisition by marriage or civil partnership | Acquisition by naturalisation | Multiple nationality permitted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

People born in Austria:

|

Austrian nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions: Conditions

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Citizenship_of_the_European_Union

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk | |||||